Fifteen years ago, at the University of Barcelona, a Catalan political scientist stated that China was the example of savage capitalism.

This declaration, taking into account the political system and the economic decision making in that countryIt seemed absurd to me.

The year 2025 is ending and, yet, almost no one questions the supposed Chinese “capitalism” anymore.

From arguments that invoke its technological advances to general statements such as “you go to China and you can do whatever you want” or “the government is experimenting with degrees of openness to transform the system little by little”. From here, a kiss for Adrián.

However, recognizing the apparent opulence and industrial development, I believe that things are not as they seem.

China was the example of wild capitalism

It is true that the Chinese government has changed a lot since Mao’s brutal communism – fortunately for the starving and suffering peasants – but It’s worth remembering what capitalism is really based on: freedom of choice and private ownership of productive resources.

The 1982 Chinese Constitution, in its articles 11 and 13, recognizes and protects legitimate private property, but this protection is more formal than effective.

Urban land belongs to the State and rural land belongs to communities, so citizens only have rights of use, normally between forty and seventy years, renewable.

Houses are purchased, yes, but always on State land. Private companies have operated under license, censorship and with the mandatory presence of internal Communist Party committees since 2016.

Private companies have operated under licenses, censorship and with the mandatory presence of internal Communist Party committees since 2016

Furthermore, the State can expropriate for “public interest”, a concept as broad as it is discretionary, even if compensation is promised. Cases like Alibaba or Evergrande show the extent to which private wealth in China is tolerated only as long as it does not threaten the Party’s power.

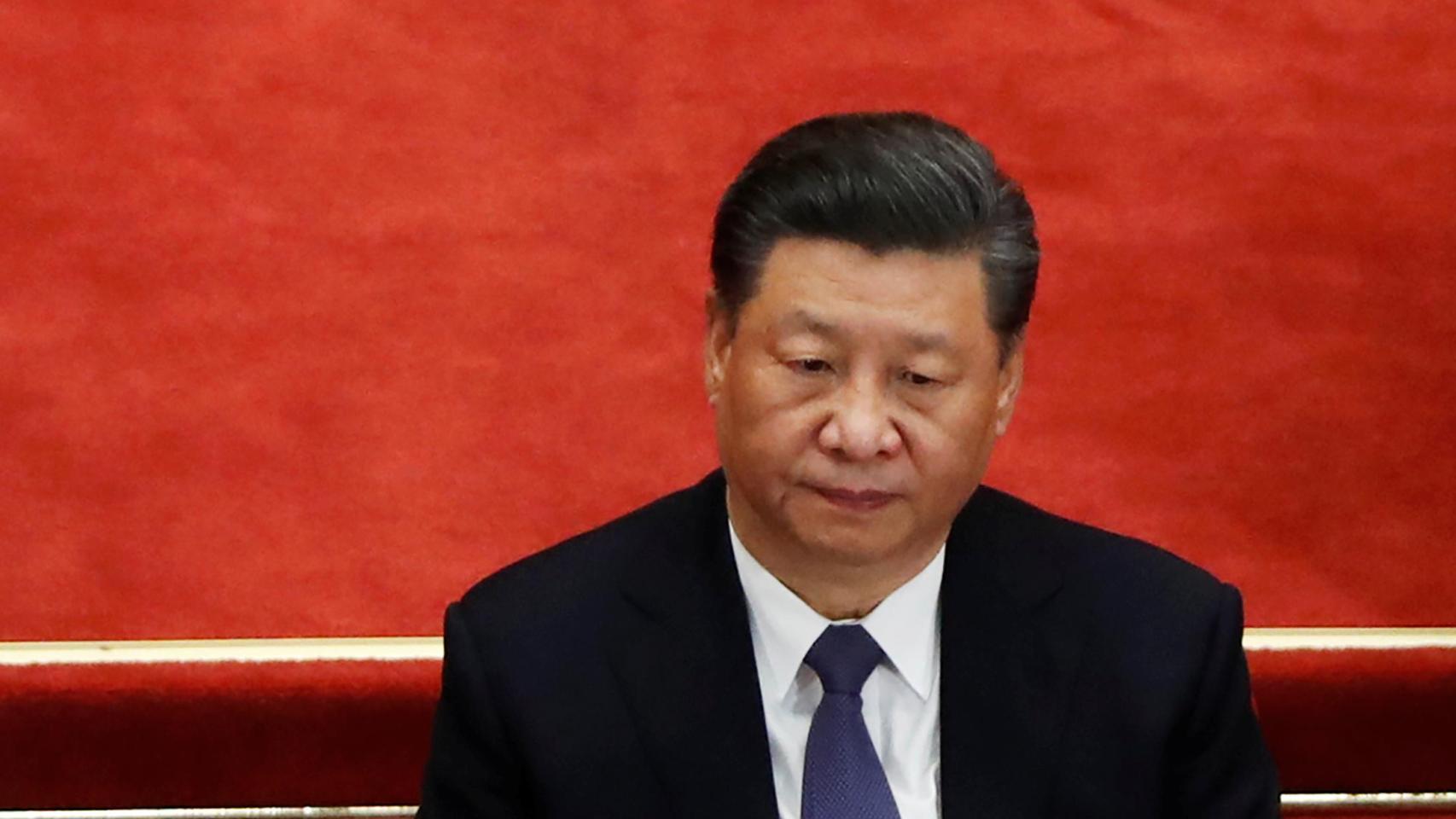

This party, the only one that exists, has almost one hundred million members. But this number, which may seem scandalous, represents only 1.7% of the population, a far cry from the image of a mass party like the CPSU in the USSR in the 1970s.

And although the number of members has increased, the front door is well guarded. Not just anyone enters. New members are generally university students with aspirations for professional or economic advancement; Many see militancy as a means of accessing scholarships, protection or circles of power.

And who really decides in the PCC? A Political Bureau Standing Committee consisting of seven people. This Board, in turn, has only twenty-five members. And the Party’s National Congress – with its 2,300 delegates, renewed every five years – limits itself to approving what has already been decided.

At the local level, governors, neighborhood committees or residents’ committees maintain some room for maneuver, but always under the supervision of a Party representative. Nobody contradicts Beijing’s orders.

Over the past two decades, China has fostered an impressive business network.

The State can expropriate for “public interest”, a concept that is as broad as it is discretionary, even if compensation is promised.

Giants like Huawei, Tencent, Alibaba any BYD They became symbols of its technological and financial strength.

In just one generation, the country went from assembling foreign products to developing chips, 5G telecommunications, artificial intelligence and electric vehicles with the capacity to compete – and in some cases, lead – the global market.

This increase is not just due to the private sectorbut rather to a state planning and subsidies strategy that channels resources to sectors considered strategic.

Scientific talent and industrial discipline did the rest. However, innovation controlled from above has a limit: when the priority is political stability, experimentation becomes dangerous and creativity becomes subject to calculation.

China has perfected a unique strategy: grant sufficient degrees of freedom to grow, innovate and design abroad, but always within the limits that guarantee political control.

It is an expanded cage, not an open door. With it, the regime is able to present itself as an engine of global growth and at the same time consolidate itself as a direct rival of the United States in the world economy.

This rivalry became visible during the first legislature of the donald trump, when the United States imposed tariffs on Chinese imports with the intention of reducing its trade deficit.

Beijing responded with equivalent measures on American agricultural and technological products, showing an unexpected resilience that ended up forcing Washington to moderate its strategy.

Far from giving in, China took advantage of the confrontation to reinforce its industrial and technological autonomypromoting programs such as Made in China 2025 and consolidating its network of internal suppliers.

The tariff war revealed that the country could not only resist the pressure, but also turn it into an opportunity to move towards self-sufficiency.

However, this formula has an Achilles heel. The absence of a true capital market limits the efficiency and sustainability of its model. Without independent institutions, without secure property rights and without free competition, China’s technological drive risks exhausting itself in the same paradox that made it possible: growing to dominate, not to liberate.