When Spaniards hear the name of Dick CheneyFew remember specific details, but almost everyone recognizes a sensation. America’s George W. Bushthe one who spoke with a Texas accent and looked at the world through the viewfinder of an F-117 in Iraq.

Cheney, George W. Bush’s vice president between 2001 and 2009, symbolized a way of governing that resonates again today (between populism, preventive wars and unlimited security policies).

Your figure, halfway between the technocrat and the hawkexplains much of the 21st century and offers a lesson that Europe, and in particular Spain, should not forget.

Born in 1941 in Lincoln (Nebraska), Richard Bruce Cheney embodies the continuity of honors course United States. Cheney has worked his way through every level of the state. He was Chief of Staff of the Gerald Fordsix-time Wyoming congressman, Secretary of Defense with George HW Bush and, finally, vice president with his son.

At each stage he consolidated a vision. The Executive Branch should act without complexes and, if necessary, above international standards, although not so much based on postulates of royal politics as well as neoconservative ideals with which (paradoxically) he did not identify.

He was the notable disciple of American political realism, one who maintained that national security justified almost everything.

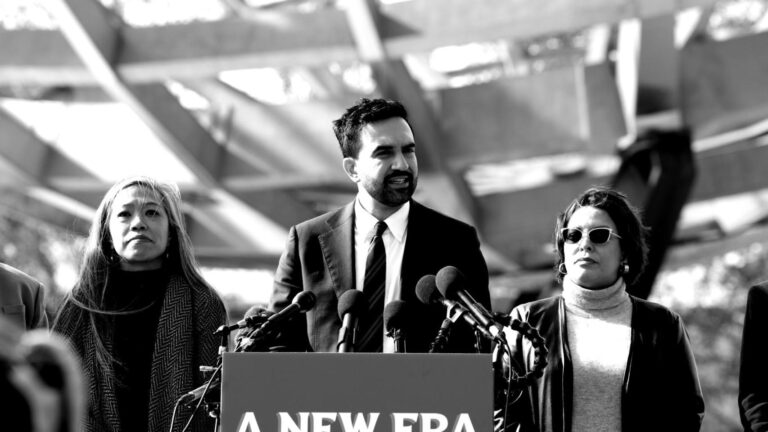

Dick Cheney oversees a speech by President Bush in Washington in 2007.

Reuters

His brilliant management at the head of the Pentagon during the 1991 Gulf War catapulted him as an effective strategist. The international coalition expelled Saddam Hussein of Kuwait in a few weeks and consolidated the military hegemony of the United States after the Cold War.

Cheney emerged from this victory decorated and, above all, convinced that “surgical” wars were the new diplomatic instrument par excellence.

Your next step as CEO of Halliburton one of the largest oil companies in the countryplaced him at the center of the industrial and energy complex that decades later would mark his mandate.

September 11, 2001, provided Cheney with her historic moment. While Bush was evacuated from Air Force One, he assumed operational control of the country from the White House bunker. There, among screens and red phones, the doctrine that defined an era was forged: the War on Terror, collective espionage as a countermeasure to terrorism and the redefinition of a non-state enemy after the fall of the USSR.

His influence was such that many analysts considered him the real brains of the Bush administration. And for the first few months after the attacks, the United States seemed to thank him that bureaucratic coldness that gave a sense of order in the face of chaosreliable in turbulent times.

Let us think about the contrast with Spain, the management of 11-M and the poisoned debate and division that still exists over it. That doesn’t exist in the United States. With the exception of a handful of conspiracy theorists, the entire society reacted and thinks the same way about 9/11.

“His obstinacy, almost theological, made him a symbol of an arrogance that was viewed with suspicion in much of Europe.”

This political and social cleansing of this event is the result of Cheney’s effective management.

But history ended up turning against him. Its unwavering defense of the 2003 invasion of Iraq (based on the fragile existence of weapons of mass destruction) became one of the United States’ greatest strategic wounds. Neither the weapons appeared nor the country managed to stabilize.

Civilian casualties, the economic cost and Washington’s moral discredit marked the decline of the neoconservative project. Cheney never admitted the mistake. He maintained to the end that Saddam’s fall was “just and necessary.”

This almost theological obstinacy made him a symbol of an arrogance that was viewed with suspicion in much of Europe.

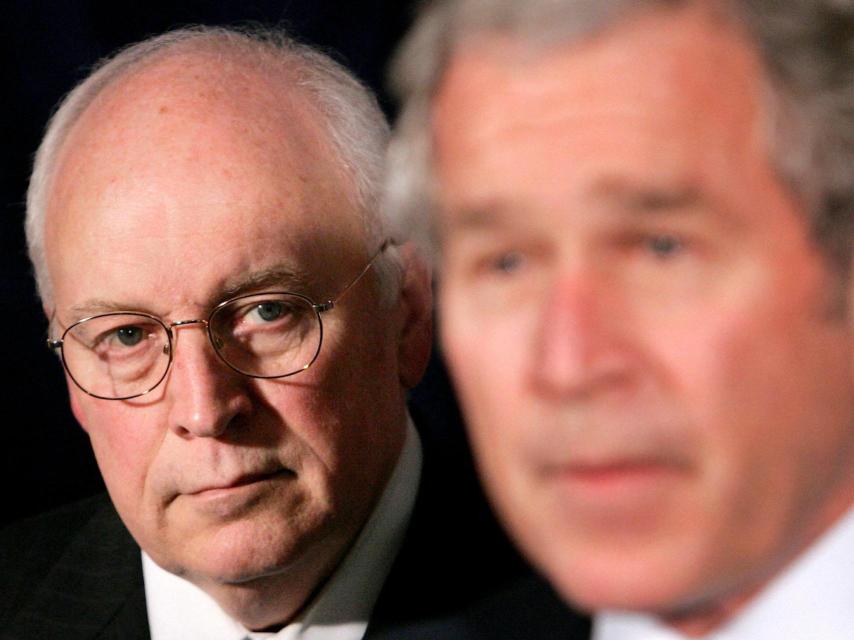

Dick Cheney in front of a model of the aircraft carrier USS Gerald R. Ford.

Reuters

The other debatable legacy was internal. Under his watch, mass surveillance programs and “enhanced” interrogations multiplied, a euphemism that history translated simply as torture in “secret” prisons. Cheney considered transparency a peacetime luxury.

The result was a profound deterioration in public confidence and the opening of an ethical debate about how far a State can go in the name of security.

Spain was familiar with this version of Washington. With José Maria Aznar In La Moncloa, the connection with the Bush-Cheney administration reached an unprecedented degree of harmony. A prosperous Spain joined the “coalition of the willing” in Iraq, authorized the use of bases and airspace, and participated in subsequent reconstruction.

“The personal relationship between Cheney and Aznar even survived Zapatero’s victory in the 2004 general elections”

In return, Washington (with Cheney as a direct link) included ETA and its network on US lists of terrorist organizations, a gesture that Aznar has always called for.

The personal relationship between the two even survived political change. In 2005, once out of power, Aznar was invited to dinner at the vice president’s official residence, a symbolic nod as the new government of José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero He withdrew troops and damaged the relationship with the White House.

This dinner sums up the Cheney style: politics as a network of personal and strategic loyalties, beyond diplomatic courtesy. For the vice president, Spain has proven to be a reliable ally in sharing his vision of the world.

It was the logic of the unipolar era of 1991-2014. Those who didn’t follow Washington were irrelevant.

Today, with the United States hesitant to focus on China or remain the global power it always was, Cheney’s legacy is once again a matter of reflection. His vision of a strong executive branch somewhat anticipated subsequent security policy (especially trumpalthough also Obama).

It also left a more diffuse mark. The belief that the international order can be reconfigured by the will of those who have the strength.

But, above all, it made two huge strategic mistakes by miring the United States in two conflicts, Iraq and Afghanistan, which absorbed immense resources that (in perspective) should have been dedicated to its true rival, China, and not fight terrorists or Taliban in the confines of the civilized world.

He passed away this week at the age of 84, his figure comes full circle. It represented the last version of the Cold War applied to a world that no longer existed: diffuse enemies, endless wars, unlimited surveillance.

But he also incarnated a determination and coherence that current Spanish leaders cannot even dream of.

*** Yago Rodríguez is a military and geopolitical analyst and director of The Political Room.