Brazil: Mosquito factory hopes to solve dengue crisis

The two Oxitec methods cannot be used simultaneously

A mosquito factory in Campinas, in the state of São Paulo, uses two new complementary technologies to reduce the transmission of dengue fever by controlling Aedes aegypti populations.

The new factory, opened last Thursday, will have the capacity to supply up to 190 million Wolbachia-infected mosquito eggs per week, enough to protect up to 100 million people per year, it was explained. The factory also manufactures products from the Aedes do Bem line, capable of reducing the population of the Aedes aegypti mosquito in urban communities by 95%.

The Oxitec Brasil factory begins operations in direct response to the World Health Organization’s (WHO) call to accelerate access to innovative vector control technologies and marks a crucial moment in the fight against dengue not only in Brazil, but around the world. With dengue cases on the rise in Latin America and the Asia-Pacific region, the facility was built to meet growing demand from governments and communities seeking rapid, scalable and cost-effective protection.

Pending approval from the National Health Surveillance Agency (Anvisa), the facility is ready to begin supplying Wolbachia-carrying mosquitoes to the government, just in time for the start of mosquito season, without the need for government funding for its construction or management.

Both biological control technologies work by releasing mosquitoes into urban areas. The Wolbachia method is designed for large public health campaigns across large areas through government programs, while Aedes do Bem is designed for targeted mosquito suppression interventions that anyone can implement in hotspots where reducing mosquito bites is a priority.

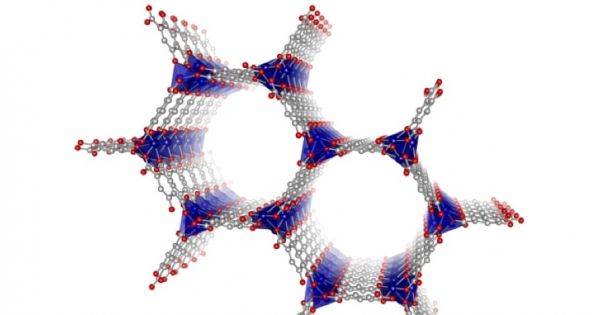

Wolbachia technology has been shown to reduce dengue transmission by more than 75% in large-scale urban pilot projects. It was formally recognized by the WHO and adopted by the Brazilian Ministry of Health as part of the National Dengue Control Program (PNCD). Wolbachia is a bacterium naturally present in more than 60% of insects, but not in Aedes aegypti. Australian researchers planned to transfer this bacteria into Aedes aegypti to see if it could reduce its viral load. The bacteria reproduces where the virus would reproduce, preventing its replication. It works in a similar way to a vaccine. When a female with Wolbachia mates with a male in the environment, all descendants of this crossing will have the Wolbachia bacteria and will not be able to transmit dengue, Zika or chikungunya, explains Natalia Verza Ferreira, executive director of Oxitec Brasil.

The difference between Wolbachia and Aedes do Bem is that, in the latter case, male mosquitoes are released into the environment, where they mate with females already present and are responsible for biting and transmitting the disease. “The descendants of this ‘couple’ will only be males, and all females will die. It is as if it were a specific larvicide for females, since females die in the larval stage. Aedes do Bem controls the population, reduces the number of females that bite and, consequently, reduces the disease”, said Verza Ferreira.

However, the two technologies cannot be used simultaneously, because if both are released at the same time, the Aedes do Bem male will mate with the female with Wolbachia, there will be no females and Wolbachia will not be transmitted to the offspring.

“The experts’ recommendation is to first suppress the population with the good Aedes do Bem and then immediately use Wolbachia to vaccinate the remaining mosquitoes so that they do not transmit diseases,” added the expert.

The application protocol consists of using Aedes do Bem during a season, which in Brazil runs from October, when it starts to get hotter and rainier, until May, when it starts to get colder. Two months after the end of this season, it is now recommended to start using Wolbachia.

“The release of Wolbachia occurs between nine and fifteen weeks. This period will depend on the efficiency of the crossing to transmit the bacteria to offspring. This can occur faster with heat and slower because, with lower temperatures, the mosquito’s life cycle is prolonged”, recommends Verza.

He also recalled that both technologies were made available to the Ministry of Health as public prevention policies.

“Brazil has suffered devastating dengue outbreaks in recent years. The urgency to act has never been greater. With the new Oxitec complex in Campinas, we are prepared to respond immediately to the Ministry of Health’s plans to expand Wolbachia, ensuring the technology can reach communities across the country quickly and cost-effectively,” he said.

Fabiano Pimenta, from Anvisa, stated that the agency was “very interested in finding a solution to make available”. (Source: Agência Brasil)