I was thinking about writing about Ferran Torres’ statements after the game against Elche: “We made mistakes in some moves, but I’m grateful that we are once again eating grass like last season”. It didn’t seem to me that what was said was related to what was seen on the ground. But the statement had an echo that excited Barcelona fans. I thought two things. First: how eager people are to believe. Second: how much power words have.

In the midst of reflection I received news that took me back to childhood. I was born in a city where professional football was a wonderful mystery sustained by words. The victorious voice of the radio that told us about the games, the newspapers and sports magazines that prolonged the emotions, the effusive coffee conversations, where the most expressive ones crystallized the legends. There were players who became mythological thanks to these stories that activated my imagination. One of those stars died this week, his name was Daniel Willington. He never played in a World Cup or was part of any of the big five in Argentine football. But it inspired my dreams when football was an unlikely goal and scared me to death when I achieved it.

He was tall and moved with the elegance of an aristocrat. He had a bohemian style of tango, he didn’t have much discipline and his game had the typical flaws of those who prefer to play in the shade rather than the sun. Of course, he improved every ball he touched and served as a tray for the attackers. The “Negro” Fontanarrosa evoked this in his story The exorcist: “Willington raised his right leg with the slow, measured movement of a heron, until the foot reached the height of his own head. And the ball, the madman, the furious, the maddened, landed on the toe of that right foot to lie there, meek, calm, like the hawk that finds the gloved hand of its owner. I have no other weapon than literature to give him an idea. They beat him a lot, but he was brave to receive it and smart to give it back. As for his Strikes, on still or moving balls, had telescopic precision, the delicacy of those herons and an equine power.

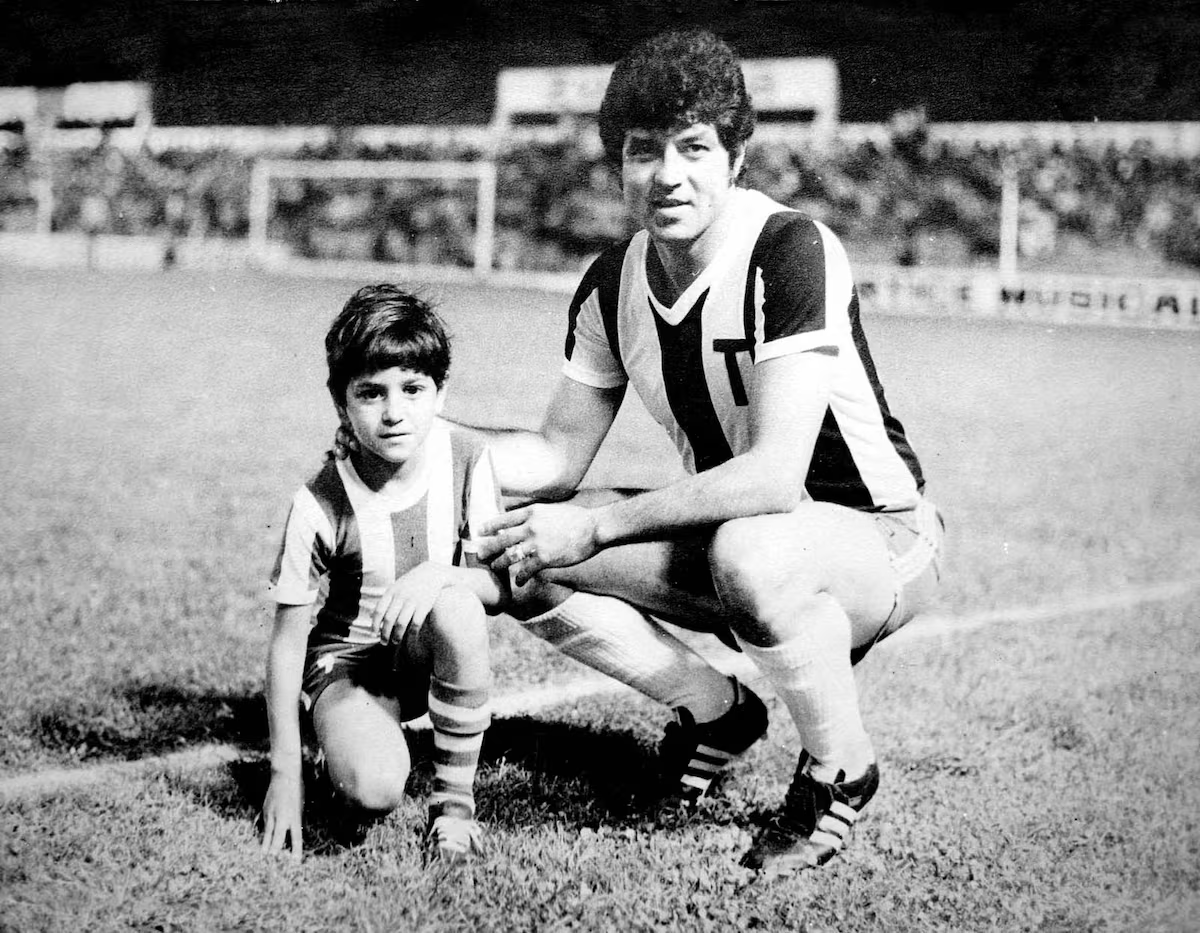

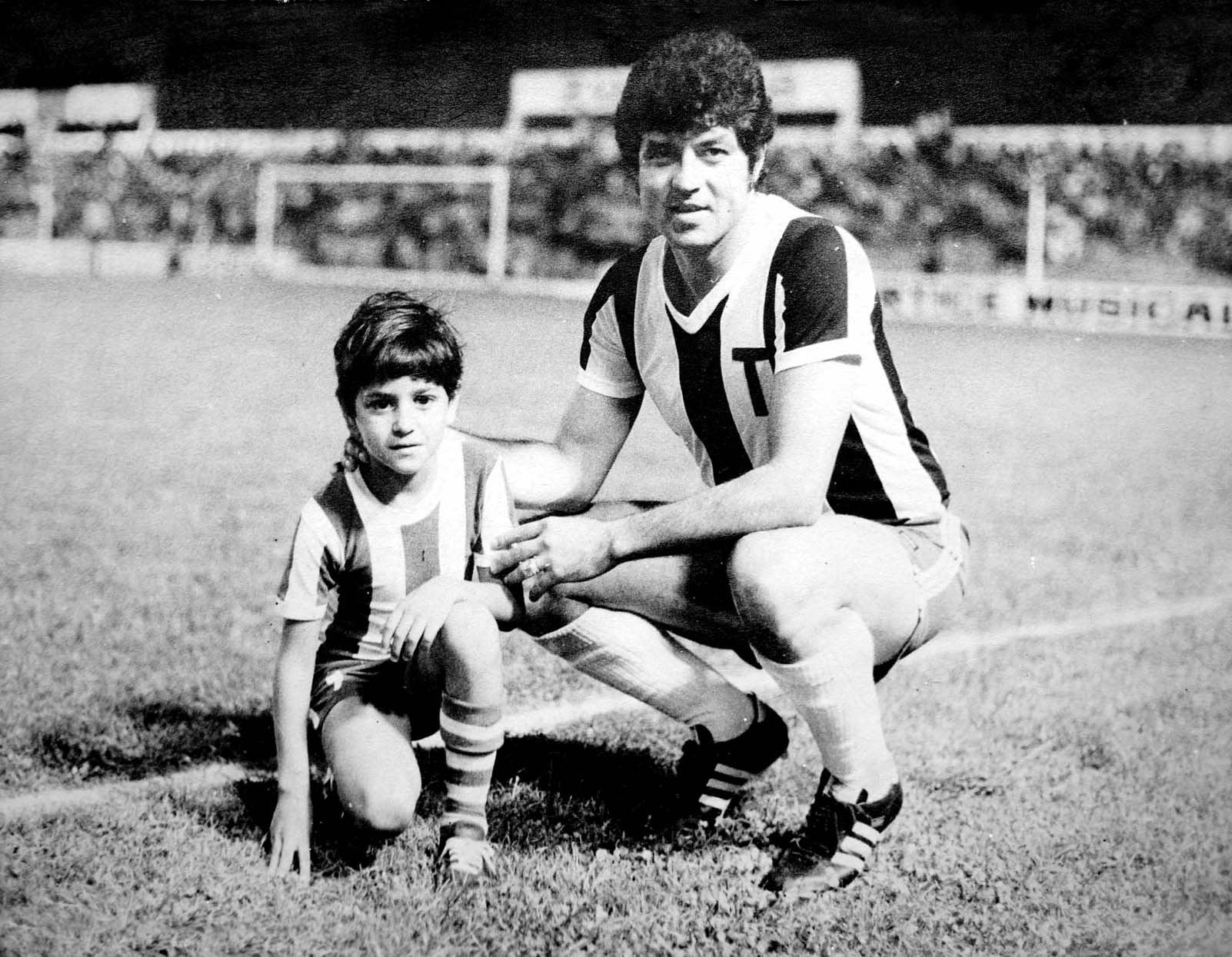

And now comes the scare. My professional dream had recently come true and I had to play in Córdoba, where Willington had his kingdom. He played ten years at Vélez Sarsfield, where he is still honored, and returned to Talleres de Córdoba, his home club, where he is also their biggest idol. I was 18, he was comfortably over 30. Halfway through the first half there was a free kick more than forty meters from our goal. I remember the location: exactly where the central circle line is closest to our area. The center circle! Our goalkeeper asked for a wall of two, which seemed extravagant to me. But I obeyed, I was one of the two. He stood out on his right leg, as serious as a god and with his head always held high.

I looked at him, mesmerized by the effect of so much literature: that guy was “El Daniel”, as they distinguished him in Córdoba. And then yes, he hit it with such purity that when the ball went over my head I could even read the price of the ball. As for power, it almost broke the beam. It was then that I thought: “if that’s what being a professional means, I’m no good”. A mortification that lasted some time. Until I understood, resignedly, that there are guys who are on another level. And we must say goodbye to them with all honors. That’s also what words are for.