When Jacobo Timmerman, in the office of Horacio Rodríguez Larreta Sr., created, with the help of Horacio Verbitsky, the large editorial office of La Opinión in 1971, both journalists represented the crossing of two generations: Timmerman, those born in the 1920s; and Verbitsky, born in the 1940s. Each recalled journalists of their generation, who had very different professional and political conceptions. This clash sparked creative magic, though the experiment was later spoiled by internal and external magic cultivators.

Daily journalism is also a generational intersection between journalists. For example: For coverage of the 2026 World Cup, a first-time journalist is just as important as a journalist who has already covered five World Cups. Freshness and experience are needed to build a balanced but not outdated vision.

Change of guard. Today, the first digital transformation leaders are retiring from working in the media field. They were leaders at the end of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century, so they led unimaginable transformations. It’s the baby boomer generation, which today coexists in newsrooms with X, Y, and Z.

Authoritarians don’t like this

The practice of professional and critical journalism is an essential pillar of democracy. This is why it bothers those who believe they are the bearers of the truth.

They were the leaders who pushed their journalists to go to the networks to learn new narrative techniques and techniques. They used to be overworked and conflict-ridden newsrooms due to increased multitasking, but in some cases, these transformations have been made so well that many “traditional” media outlets, even dating back centuries, today can be called emerging media and are great innovators.

Now these leaders publish memoirs in which generational differences are a constant theme.

They include editors from El País, El Mundo, The Washington Post, The New York Times and The Financial Times. It is relevant because the Anglo-Saxon and Spanish press are the main references for our newsrooms.

Former Financial Times editor Lionel Barber wrote in The Mighty and the Damned. Life behind the headlines The Financial Times, which sees in new generations more cooperation, disruption, participation and greater use of open sources of information, adds that technology is never just a technological challenge, but a profound cultural change.

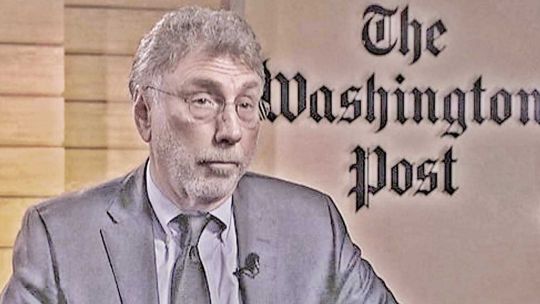

One of the most prominent memoirs of this wave is Martin Baron’s book Against Authority. Trump, Bezos, and the Washington Post. A few years ago, Berville organized a preview of the film Spotlight, an Academy Award-winner for best picture, which describes an investigation Barron conducted, as editor of the Boston Globe, into that city’s bishops’ protection of pedophile priests.

Barron, who now offers training workshops for editors in Colombia with Conectas, says in his book that he was on the verge of resigning from the Washington Post because of a conflict with its editorial team over generational reasons.

The historical tradition in Anglo-Saxon journalism has been for journalists to maintain some restraint about their own positions. But when the United States exploded over the case of George Floyd, the African-American who was choked to death with his knee by a white police officer, the Washington Post editorial staff was seething with indignation. Journalists expressed their open defense of the cause in every possible way: participation in rallies, donations, signing of petitions, expressions on networks, epithets in their texts and videos, and explicit support for the Black Lives Matters organization.

Barron, who grew up old school, feared the public would see journalists as activists: “Every profession has some limitations, and we have ours.” In a memo to one of his bosses he said: “There is a new generation in this field who wants to take journalism at The Post, The New York Times and other organizations in an activist direction.”

For Jill Baron, this affects credibility: “I can only imagine the reaction among staff if I, as an executive editor, had marched for a cause that went against what many in the newsroom believed,” he says.

In a more recent article, Baron wrote: “We want objective judges and doctors, so why not objective journalists, too?”

Because of the same problem, Antonio Caño, who was director of El País newspaper in Madrid, had a crisis with the editorial team. In his memoir, Tell the Truth. A journalist’s memoirs and observations about an endangered profession. He says that he prepared a document to regulate the use of social media networks by his journalists, but the editorial board rejected it.

The editorial team interpreted it as a limit to their freedom. “I accepted the argument, even though I did not share it, and withdrew the motion,” he wrote.

“The journalist is not an activist,” Canio said in his book. “He is perhaps the opposite of an activist. His mission is not to end racism or protect the disenfranchised, or to insist on examples about the legitimacy of which there can be general consensus. His mission is to reflect the seriousness and complexity of these problems, which sometimes requires gathering the views of those who strike us as racist or sexist. And to do so in an honest and respectful way, not in a convoluted way to cover the appearance of neutrality.”

But this advocate believes it is possible that the public’s perception is that these veteran leaders can sometimes be covert activists, resorting to formal notions of objectivity.

In many cases, objectivity was contrived and simulated, where false moral and epistemological equations could be constructed.

Another accomplished editor is the Filipino Maria Ressa, who is also the winner of the 2021 Nobel Peace Prize, along with the brave Russian journalist Dmitry Muratov. She interned at CNN and later became the most prominent journalist in her country. It questions notions of neutrality or equidistance, close relatives of traditional objectivity.

In his book How to Fight a Dictator. What are you willing to sacrifice for your future? He says: “An objective journalist does not exist (…). A good journalist does not look for balance (…) A good journalist, for example, will not devote the same time and space to known climate change deniers and the scientists who study it.”

In a recent speech he said: “In the battle for facts, in the battle for truth, journalism is activity.”

In Editorial Perfil’s editorial offices, everyone from Baby Boomers to Generation Z coexists, and for this advocate, every generation has something to say.

In journalism, creative magic always arises from effective and honest dialogue between generations.