The first time I dared to put the word “strike” in a headline for the Cambio 16 channel, of which I was executive director, my pulse trembled. “Hit Perkins” no less. In March 1972, dictator Francisco Franco was at his best. The strike was banned by him when he won the civil war with essential assistance from Hitler and Mussolini. Since then, it has become a crime and a taboo word. No one dared to write about it. My address has not been pre-censored. The Franco regime’s censor, Alejandro Fernández Sordo, threatened to send the police to confiscate the entire print run if I did not change the “Strike at Perkins” to an artistic stoppage or temporary suspension of production. Not without the pain and economic cost of having to change the paper, we meet your demand.

Three years later, with the death of the dictator, Fernández Sordo himself was appointed Minister of Unions, and this was his first full-page statement in the newspaper Pueblo: “From now on, we will call the strike a strike.” It is impossible to avoid smiling. At the speed of a turtle, and without exposure to political or economic risks, we were victorious over freedom of expression, word after word.

Writing Democracy did not satisfy Franco’s censors either. For this reason, we have chosen to use the word Europe, perhaps offensively, as a synonym for democracy. We wanted to Europeanize Spain. The pages and covers of our weekly newspaper were filled with headlines bearing the word Europe: Europe, the Beloved Homeland; Europe, yes. And Japan as well; Goodbye Europe, goodbye; europe game; No, this country is not suitable; Europe is moving away… That was a good excuse. We have circumvented censorship several times in this way, although it was not always possible.

On October 9, 1972, our first wedding anniversary, we suffered another unexpected shock. I got the exclusive by pure chance. EFE sent a note to its subscribers canceling the news of the princes’ trip to Germany. I called reporter Michael Vermehern and asked him about that visit. “I really liked the interview I did with the prince about Spain in Europe,” he told me. I asked him to translate the prince’s words for me, and I went directly to his house. I was left in one piece:

German TV:

-Does His Royal Highness want Spain to join the European Economic Community…?

Juan Carlos de Borbón:

-Yes. I hope so. Because I think it suits Spain and Europe.

Europe closed the door in our faces every time Franco asked to negotiate something. Now, this may seem trivial, but I considered that interview a journalistic bombshell of the highest order. On the cover, above the caricature of Don Juan Carlos, emerging from his head, we placed this large headline with a giant body:

“Europe, yes.” As soon as the Ministry of Information received the ten pre-censored copies with my signature on their covers, I received an angry call from the Director General of Press. He called me everything. Putting the words “Europe, yes” into the prince’s mouth was like mending the rope in the house of the hanged man. He told me that the police would go to the printing house and confiscate the entire printed copy. At that moment, I suffered more for the loss of exclusivity than for the democratic future of Spain. I replied: You will know what to do, but I do not believe that the prince made these statements without consulting anyone. Moreover, when Juan Carlos is head of state, how will you explain to the king that he prevented him from meeting?

A few hours later, I received a phone call from Fernandez Sordo. He told me he made a personal effort to get the Cambio 16 to newsstands without anything bad happening to us. The press quickly repeated what it called “the question” to the prince, turning “yes, I want it” into “yes, I want it.”

Kidnapping, fines, prosecutions

They say that real power is arbitrary power, which is not subject to restrictions by other powers. This was the case with the dictatorship. Franco concentrated all the powers of the state and exercised them without limits as it suited him. Only what satisfied them was published. For this reason it was very difficult to know when the actions of the executive, legislative or judicial power, completely controlled by the dictator and his delegates, were tightened or relaxed. Since there were no rules, we wrote and posted with the same risk of losing a 7:30 game: you either get through or you don’t. If it did not arrive, readers would know nothing about labor or student struggles or, for example, the torture in the basements of the Directorate General of Security (DGS), the headquarters of the Community of Madrid today. However, if you go too far, (unfortunately!) If you go too far it will be worse because you are putting your post at risk and you could end up before a public order court or being interrogated at the General Directorate of Public Security. I had to go there three times. They told me as a guest.

Franco eased the pressure on journalists’ necks slightly by approving the 1966 Press Law, promoted by his minister, Manuel Fraga Iribarn. It replaced Serrano Soñer’s testimony of 1938 according to which the journalist was “… a messenger of thought and faith of the nation that has regained its destiny (…) a worthy worker in the service of Spain.”

Article 1 of the Fraga Law provides for the right to freedom of the press. Under Article 2, this right has been so arbitrarily restricted that it has almost completely disappeared. However, he brought about a change that was attractive to new generations. Mandatory prior censorship disappeared and became voluntary censorship. The printmaker could publish whatever he wanted without subjecting himself to prior voluntary censorship, but he risked suffering the consequences of his recklessness.

A newspaper or magazine that was published without prior censorship was subjected to police confiscation of publication, prosecution of its author and director, and even the final closure of a media outlet that did not satisfy the dictatorship. This was the case, among others, of Diario Neville, of which I was editor-in-chief, and who was born on December 31, 1969 and died at the hands of the police on the same day she was born. It was approved by Fraga and erased with the stroke of a pen from the official press record by order of his successor, Opus Dei Minister Alfredo Sánchez Bela.

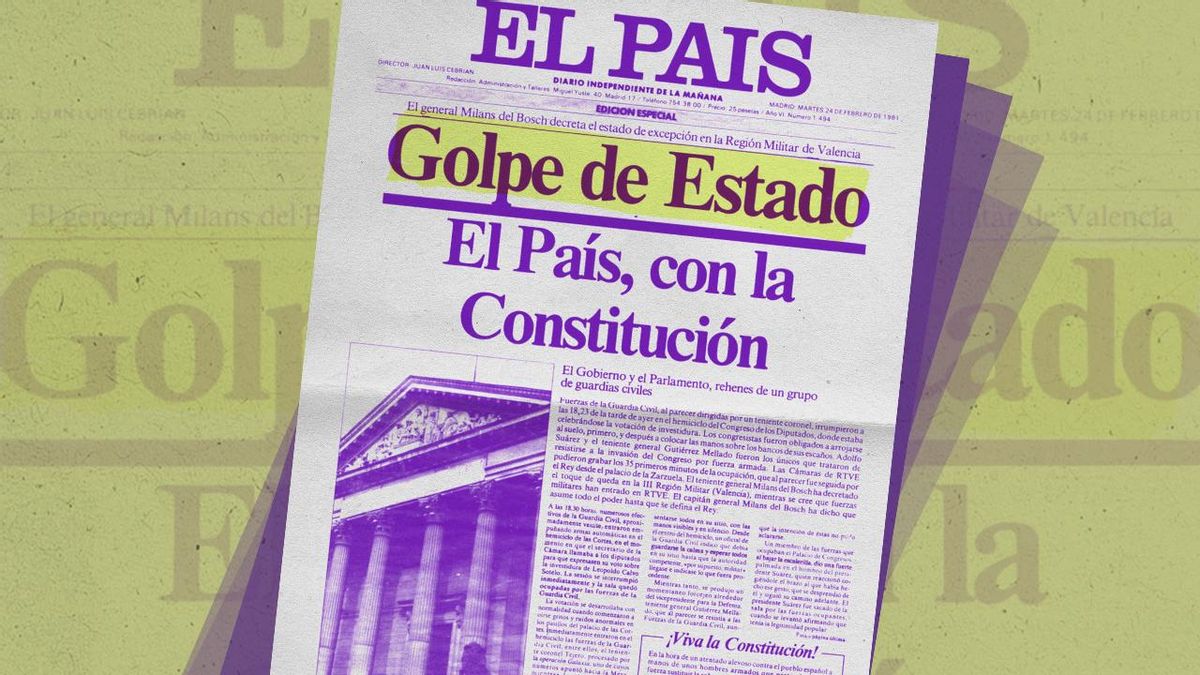

Against the coup

This cover is a slogan and a commitment. El Pais’s response to the 23F coup exemplifies what journalism should be. A tribute also to the newspaper workers who were victims of the fascist attack on October 30, 1978.

The following year, in 1971, the government issued a decree closing the Madrid newspaper. It evolved from its clearly Francoist positions after the Civil War to others that were somewhat more independent of the regime. This opening cost him his life. Soon after we witnessed the stunning bombing of the Madrid newspaper building, a terrifying and unforgettable image for those of us who were fighting from below to seize freedom of the press.

At Cambio 16, which was born in the same year that the Madrid newspaper was closed, we took note of this and decided to subject our weekly newspaper to prior censorship. We have also chosen to include on the central sheet (which is easy to tear off) topics that censors may not like. Our weekly newspaper was subjected to several hijackings by the police while I was negotiating with the censor to change the publication in order to obtain permission to distribute copies. The same thing happened to us in 1974 when we founded the weekly magazine Doblon dedicated to skillfully and wisely condemning the rampant corruption of the Franco regime. Without freedom of the press, everything was corruption in a dictatorship. Our cover of the magazine “Sofico Hopeless” (with several generals on its board) quickly turned us into an independent and… profitable magazine of reference.

As founding director of Doubloon, from 1974 until I fled to the United States in 1976, I was tried dozens of times for alleged journalistic crimes by ordinary and public order courts (from which I received a pardon after the death of the dictator) and once for incitement and insulting the army by a non-pardonable military court for my article on changes in the Civil Guard. Being the first Spanish speaker to receive an award from Harvard’s Nieman Foundation for Journalism freed me from the corresponding court-martial. With the President of Harvard’s telegram in hand, I asked José Vega, Commander-in-Chief of Madrid, to permit me to leave Spain with my obligation to appear before the military court as soon as I was summoned. The moderate Captain General Vega was replaced by Francoist General Ángel Campano as Director General of the Civil Guard in the last cabinet headed by Franco before his death. Vega helped bring down my alleged crime against the army.

Ten hours of torture at the hands of the Civil Guard

In February 1976, Doubloon published several cases of transfer and dismissal of senior Civil Guard officers in Vega and their replacement by those loyal to Campano. This indicates a complete purge to control the 70,000 permanently armed and mobilized men from the Benmira tribe. Amidst the saber-rattling, whoever controls the Guardia Civil (which is no longer a pineapple) controls Spain.

We managed to stop the clearance operation, but I was kidnapped by commandos armed with automatic rifles when I left my home. Campano’s civil guards tortured me during my ten-hour interrogation in the Guadarrama mountain range. In the end, they subjected me to mock firing, with a gun two inches from my forehead, until I told them who had leaked the details of the purge to me. I thought I was going to die. They wanted him to accuse General Saenz de Santa María, Campano’s second-in-command inherited from General Vega. My anonymous sources have given me the data from the official bulletin over the phone where I can check the changes. I didn’t know what to say.

Finally, on the third day, they shot me, and I heard a shot, but there was no bullet. They forced me to sign an official document against General José Antonio Saenz de Santa María on March 4, 1976 in Guadalajara, and around dark, they ended up releasing me on top of the mountains. When I left the hospital, on the same night of March 2, I informed the court on duty that they had forced me to sign a document dated in Guadalajara two days later, without remembering its content. I never mentioned the Guardia Civil of Campano, as the perpetrator of my kidnapping, until 30 years had passed and their crimes had come to light. It happened. It could happen again. I choose to forgive, but not forget. Of course, I have never forgotten the fear I experienced three months after the dictator’s death. Also, freedom of the press (an achievement, not a gift) is like oxygen. You appreciate it more when you lack it.