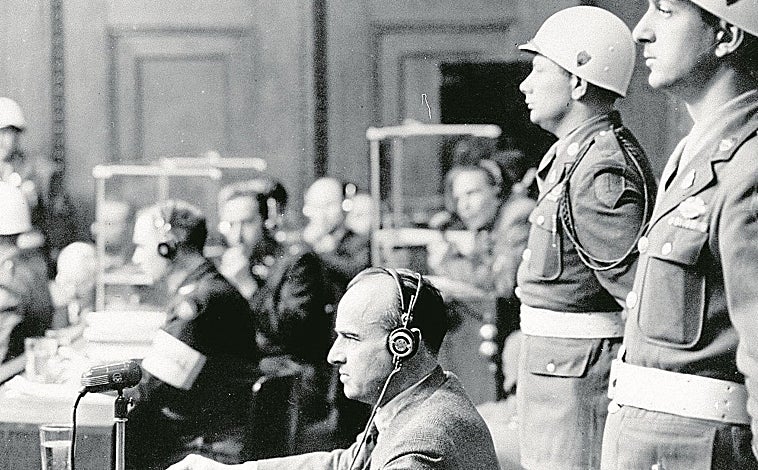

This week, Germany will return to Room 600 of the Palace of Justice Nuremberg, The trials of Nazi leaders began 80 years ago, which would represent, de facto, the founding event of international criminal law. It was an unprecedented trial … It lasted 218 days, during which the court had access to more than 300,000 sworn statements and heard from 240 witnesses, who together composed a story of limitless cruelty and dehumanization. The International Military Court issued rulings that included the death penalty for twelve of the accused.

Today, academic institutions, human rights advocates, and international organizations are coming together on the anniversary to reflect on the legacy of those trials, which allowed Germans to start from scratch, at least partially settle responsibilities, and begin to clean up the moral devastation to begin building a new society. But for some of them, the Nuremberg process never ended. The Nazi children who were tried in that hall were indirectly sentenced to life imprisonment with the penalty of shadows and contradictions. They were born under the weight of a stigmatized title and phrases that affirmed their lineage of pure evil. Questions about how to reconcile a filial role with an aversion to crime still resonate in the hearts of the Nuremberg children. Some of them devoted a large part of their lives to recovering their inheritance on the basis of truth and responsibility.

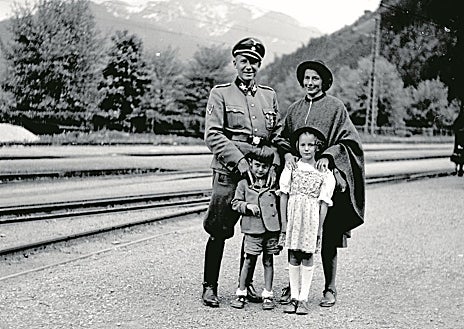

Niklas Frank He was born on March 9, 1939 in Munich into a high-ranking Nazi family. mother, Hans FrankHe was Adolf Hitler’s legal advisor and was appointed Governor-General of the occupied Polish territories in 1939, where He earned the nickname “Butcher of Poland” because of his cruelty.. He was responsible for the labor and extermination camps at Auschwitz, Sobibor, and Majdanek, and the ghettos in Warsaw and Krakow. During his reign, the “Final Solution” policies were implemented and millions of Polish Jews were killed. He ordered summary executions, deportations and collective punishments against civilians.

-U00056811427gQw-278x329@diario_abc.jpg)

“Here we started with 3.5 million Jews, of whom only a few companies remained. “Let’s say, everything migrated,” he joked triumphantly at a reception on August 2, 1943, at Wawel Castle, the residence of Poland’s Nazi-occupied kings. In his memoirs – more than 11,000 pages long – he documented the crimes for which he was sentenced to death at the Nuremberg Trials in 1946. At no time did he show any remorse.

His son Niklas was 7 years old when the “Butcher of Poland” was executed. “I remember seeing reports on TV in Wochenschau. Every week there was a report on the trials, and I, who did not understand what was happening, was proud when the camera focused on my father.I remember visiting him later one time in prisonin September of ’46. I sat on my mother’s lap and my father was on the other side of the glass. On the right and left are two armed guards.

“Why would my father lie to me?”

That summer, the lawyer visited his mother to tell her there was not much to do. The evidence against his father was overwhelming. “We knew we had ten minutes to talk to him and it would be the last time. But he smiled and told me that we would celebrate Christmas together again soon. For the first time I felt deeply disappointed as a son. I kept thinking: “Why would you lie to me, if you knew they were going to hang you?”».

For years, Niklas was too busy trying to survive. After playing in rooms whose walls hung Leonardo da Vinci’s “The Lady with the Ermine” and several Rembrandt paintings, his family was forced to beg. Only as the years passed did he become aware of the crimes tried at Nuremberg and their scope, which caused him enormous pain. “In my house there was no talk about it, about the Holocaust, nor about what my father did. Then everyone in Germany wanted to put an end to and forget about the Nazi era. “I studied, worked, got married, and had a daughter,” but fatherhood increased his need for exorcism, and finally, Breaking the silence in the book “The Father”. “the account, Published in 1987. He turned his pain into a commitment to fight forgetfulness and hypocrisy. “That was the year it was published, but I decided to write it long before that. He was very angry with Germany, and saw the silence about the Holocaust, the evasion and hidden anti-Semitism everywhere. I decided to face the truth. “It turned out that I was the son of that mass murderer and I had to write very clearly about my father,” he sums up his motivations. He also asserts that “the book was widely read, but at that time it was a scandal: Stern magazine published six chapters in a row and there were hundreds of criticisms against me.” Not positive. It touched a chord that is still alive today with the grandchildren, because their fathers and grandfathers remained silent. I said things publicly. This affects people.

Now, eighty years after the Nuremberg process, Niklas Frank lives this memory with a degree of anxiety and doubt. “We should have understood the meaning of the Nuremberg trials, but I don’t think so. “It seems that the Germans are tired of democracy, as if they once again want a Führer or a leader who decides without parliamentary debate and tells them where they should go.”

The rise of the Alternative for Germany party

In a country immersed in an intense rearmament process, the first opposition force in the Bundestag is the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), a populist, authoritarian-nationalist formation that is classified as far-right and openly pro-Russian. His position has become very solid in most parts of the eastern region, and according to many opinion polls, he could win elections at the federal level. “I would not be surprised if we have a tyrannical and criminal government again in the coming years,” predicts Frank, who laments that “the Nuremberg trials no longer have any role in history lessons: they mention it, but they do not delve into it.” “Trial records are printed. You can read how cowardly the Nazi leaders were in court, how they tried to get out of the way, blamed others and hid, saying they were just following orders. This does not matter to anyone today. Only on November 20 will it be forgotten again,” he says sadly.

“Trial records show how cowardly the Nazi leaders were in court.”

Niklas Frank

Son of the “Butcher of Poland”

Not all children Of those condemned at Nuremberg They took the distance Their parents’ morals. Architect Wolf-Rüdiger Hess, son of Rudolf Hess, Hitler’s lifelong lieutenant who died in Spandau prison in 1987, argued for his father’s innocence until his death in 2001. But the public revelation of the trial weighed on many of them in favor of distancing themselves. Other examples include the descendants of Albert Speer, Hitler’s Arms Minister. Although three of the eight judges, two Soviet and American Francis Biddle, supported the death sentence, the rest resisted and the verdict was reached after two days of debate. Speer was sentenced to 20 years in prison. His case raised suspicions, but his daughter Hilde Schramm became active in memory and justice projects.

However, descendants of Nazi leaders who managed to avoid the bench tolerated silence better. Gudrun Borwitz, the daughter of Holocaust mastermind Heinrich Himmler, continued to maintain her Nazi sympathies until her death in 2018. Henrik Lenkhet, who discovered a year earlier that his grandmother had been Himmler’s mistress, admitted to ABC: “I haven’t gotten over it, I’m still immersed in the process of mourning, anger and identity rearrangement…” Lenkhet is an evangelical pastor. In Malaga, he is looking for a publisher for his book. He wants to follow Frank’s example. For many years, Niklas carried a photo of the body of the “Butcher of Poland” to confirm his death. Today, at the age of 86, he also carries in his pocket a photo of his deceased wife, daughter and three grandchildren. “Now I look at it and I think I managed to escape that ideology.”