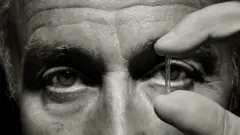

Image source, Courtesy of Julio Palmas

-

- author, Tim O’Callaghan

- Author title, BBC World Service, Watch History series.

“It was like a lightning bolt. I started thinking about it at the time, and I was actually drawing pictures on the way home on a napkin on a plane.”.

This is what Dr. Julio Palmaz told the BBC when he recalled what happened to him in 1978 after attending a conference by Andreas Grünzig, author of the first successful coronary angioplasty.

What the German cardiologist did was insert an inflatable balloon at the end of the catheter to widen the blocked artery, forever changing the role of the cardiologist in treating cardiovascular disease.

But the procedure showed a high rate of recurrence of clogged arteries.

That’s why Palmaz set out to create an alternative and made it happen.

for him pillar The balloon-expandable coronary artery is one of the most successful medical inventions of the past 30 years. An estimated 2 million are implanted in people’s hearts around the world each year.

Palmaz was born in La Plata, Argentina, in 1945. After receiving his medical degree in 1971, he was drawn to medical research.

“I was trying to find a direction in my career,” he says. “I discovered the American research mechanism and thought it was a dream for people to get paid to do research, which was a privilege for me.”

“Research was not possible in Argentina, so I knew that if I wanted to contribute, if I wanted to put my foot in the fresh cement, so to speak, of medical knowledge, I had to go to the United States.”

Palmaz began working in the radiology department of a hospital in California.

A year later everything changed in his life.

“Since I was a first-year radiology resident, I really had the attitude of trying to do something, looking for an opportunity to make my mark,” he says.

He found it in New Orleans, when he heard Gruentzig at that conference.

“His presentation was very informative and he was very honest about the limitations of balloon angioplasty. This sparked the idea of creating an implantable scaffold, which was essentially the beginning of the stent.”

The solution is in the garage

Let’s stop to remember the basics.

Coronary heart disease is a disease that affects the coronary arteries, which supply oxygen to heart cells.

Clogged by fatty substances; As blood flow is restricted, less oxygen reaches the heart, which can lead to a heart attack.

Fortunately, there are options to help manage coronary heart disease.

Image source, Abu Felsen

In the 1960s, the main way to do this was by cardiopulmonary bypass, where a vein is taken from another part of the body and used to bypass blocked arteries and flow back to the heart.

It was a large and invasive operation.

Balloon angioplasty, on the other hand, is performed when – through a catheter – a small balloon is carefully guided through the artery into the blockage and then inflated to increase blood flow.

Now let’s go back to Palmaz.

In 1978, his idea was to build a scaffold that could be placed over the balloon and then used to keep the artery open longer. So he started looking for ways to make this happen.

“At first I was trying to make very simple prototypes in my garage, trying to weave copper wire and a soldering iron around the pencils. I quickly realized that they had to be interlocked to have any cohesion,” he says.

“At the time, there was some construction work going on at my house and the workers accidentally left an expanded metal bracket with overlapping slots.”

“When I saw that, I thought maybe this was the solution,” he recalls. “I closed the mesh and the stepped diamonds turned into stepped grooves… And I found the solution: not using woven wire mesh, but using a solid tube with stepped grooves.”

The design was exactly what Palmaz was looking for: something foldable that could stand upright once inserted and remain stable.

From fear to pride

Palmaz had his own design, but he still needed a way to manufacture it, so he went to work at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, because they had a specific machine that could make the structure he needed.

Here he teamed up with US Army cardiologist Dr. Richard Schatz, who introduced him to an unexpected investor: Philip Romano, the owner of a fast food chain.

His money allowed Palmaz to intensify his efforts to develop the prop.

But the team’s big breakthrough came when a pharmaceutical giant became interested in what they were doing.

“That in itself was a miracle for me,” he says. “I was in the right place at the right time.”

“A lot of people had huge ideas and never had the opportunity to get the interest or support of a major sponsor. I was very lucky that they were interested in the prop and decided to invest all that money in developing it.”

Image source, Getty Images

In the late 1980s, Palmaz began testing his invention in human clinical trials around the world.

“My life suddenly changed,” he recalls. “I became a traveler, traveling around the world giving lectures, training collaborators, observing experiments from every side, and eventually publishing their results.”

“And I was pleasantly surprised by the results because everything was really excellent in that sense (…) In 1990 the US Food and Drug Administration approved the stent for use in peripheral arteries and it became the first implantable stent approved for use in blood vessels in the United States.”

How do you feel when you see that something you’ve invested so much of your life in looked so promising?

“At that point I felt scared and anxious,” he says. “I couldn’t really enjoy all the success, because I was always afraid of long-term problems.”

“There are notable examples in medical history of people who tried things and problems only appeared years later.”

Despite Palmaz’s initial caution, his invention met with great success and is now one of the most common treatments for heart attack patients around the world.

“At first I thought the stent would have limited use and would be a niche application,” he says. “I never thought it would become such a major medical resource.”

“It still surprises me that after all these years it’s still in use. I definitely feel very proud and happy.”

“I have also become a mentor, so that young people at least try to present their ideas, take an innovative approach and find new things with which they can really leave their mark,” he adds.

Julio Palmas now lives in California, where he owns his own vineyard.

Subscribe here Join our new newsletter to receive a selection of our best content of the week every Friday.

And remember, you can receive notifications in our app. Download the latest version and activate it.