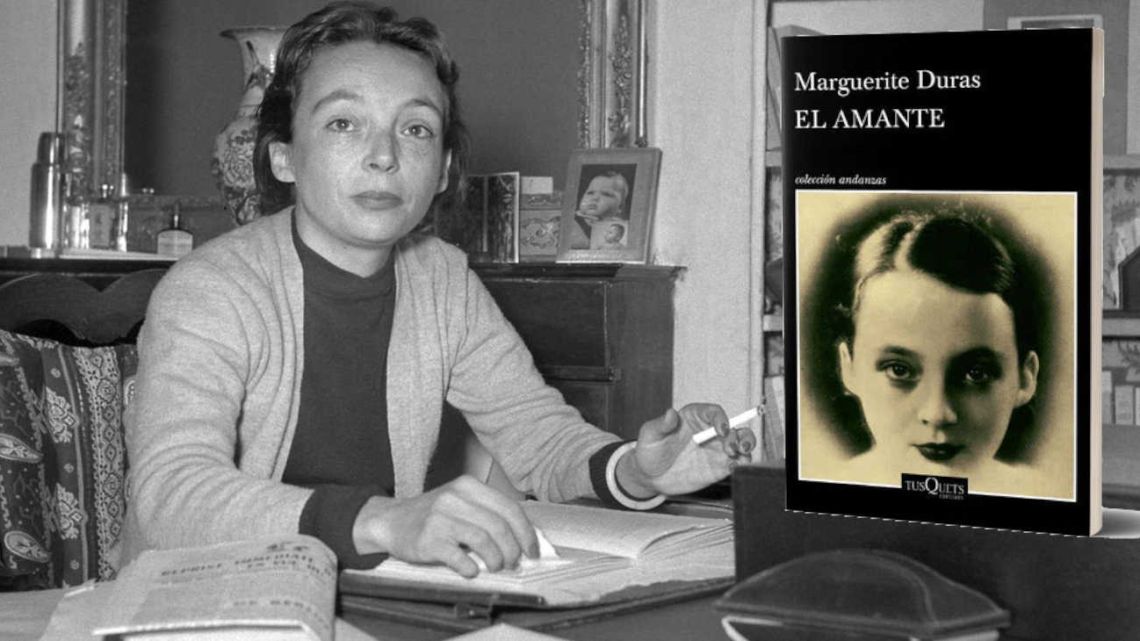

A few days after the 30th anniversary of her disappearance Marguerite Duras (Saigon, Indochina, 1914 – Paris, France, 1996), We Save That’s it (“That’s All”), a selection of things said by the author, between November 20, 1994 and February 29, 1996. The volume, published by Jan Andrea, has an incalculable value of testimonials, since she herself revised her classics.

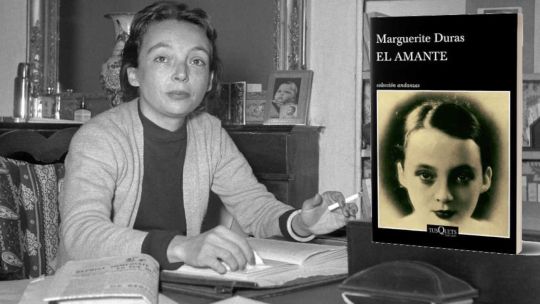

author Beloved (Prix Goncourt 1984) He envies those who do not write, and wonders how they cannot write, as has been proven Outstanding passionan interview with Leopoldina Ballutadella Torre, translated by Cesar Aira. This novel was made into a film in 1992 by Jean-Jacques Annaud.

Orphaned by her father since she was four years old, Marguerite Duras, whose real name was Marguerite Germaine Marie Donadieu, was born and lived until she was 18 in Indochina, now Vietnam, in a poor French family, with a mother she described as “lively, crazy, as only mothers can be” and her two male brothers.

Authoritarians don’t like this

The practice of professional and critical journalism is an essential pillar of democracy. This is why it bothers those who believe they are the bearers of the truth.

in Beloved (1984) is a powerful novel the biographythe novel’s protagonist, a teenager barely fifteen years old, tells the story of an intensely erotic passion with a wealthy Chinese young man. The story continues for a year and a half, after which, at his father’s request and in order to perpetuate the inheritance, the boy agrees to marry a young Chinese woman of the same socio-economic status. In the clip I show below, the little white girl imagines the wedding night of the Chinese heiress—coming, like her new husband, from the traditional families of the North—whose mistress she was with.

“He does not know how long after the white girl’s departure the father’s order was carried out, when he carried out that wedding which he had ordered him to hold with the young woman whom the families had appointed for ten years, and also covered with gold and diamonds and jade. A Chinese woman had also arrived from the north, from the city of Fo-Chuen, in company with the family.

I recognized him by his voice. “I just wanted to hear your voice,” he said. She said: This is me, good morning. I felt afraid, I was afraid, just like before. His voice suddenly trembled.

“It must have been a long time without her being able to be with her, without being able to give her an heir to the riches. The memory of the little white girl must have been there, lying, the body, there, crossed on the bed. She must have been her mistress for a long time.” He desiresthe personal reference to emotion, to the immensity of tenderness, to the bleak and terrible physical depth.

“(…) She, the little, little white girl, had never known about those events. After years of war, after weddings and children and divorces and books, he arrived in Paris with his wife. He called her. It was me. She recognized it by his voice. He said: I just wanted to hear your voice. She said: It’s me, good morning. He was afraid, he was afraid, as before. His voice, suddenly, trembled. And with a sudden tremor, she recognized the Chinese accent.

“(…) He told her that it was the same as before, that he still loved her, that he could not stop loving her, and that he would love her to death.

For a long time she must have been sovereign over it He desiresthe personal reference to emotion, to the immensity of tenderness, to the bleak and terrible physical depth.

It is an arduous moment, impossible at first, perhaps because of his decisive presence, the young white woman thinks, confident of the extraordinary power she had in the man’s life, though she tempers her re-creation of the scene with expressions that suggest possibility. Then he moves from not knowing the date of the wedding: “He does not know how long after the white girl’s departure the father’s order was carried out…” to a recurring expression of conjecture that highlights doubt while paradoxically reinforcing certainty: “A long time must have passed without him being able to be with her… The memory must have been there… She must have been the mistress of his desire, the personal reference of affection, of the immensity of tenderness, of melancholy.” And the terrible physical depth.

“…And then the day came when it should have been possible…” But in that case, she was no longer the obstacle, but the deception and betrayal. Only through the strong desire aroused in him by the young woman was the Chinese man able to achieve this meeting with his wife and, by extension, the family mandate: to be heir to wealth.

If, at the beginning of the imaginary, the previous place of the young white woman is one of exclusion, the place of the assumed reality consists of her presence in the bridal chamber and her being an intermediary in the sexual act: the Chinese must have “found himself inside that woman” through her, through her crossed body in the bed. As she somehow put it in one of the final dialogues in her other novel, The North China Lover, in reference to the suffering she inflicted on them and on herself: “…You too will marry for me.”

The conjecture then turns to the feeling of the Chinese girl, one who was certainly aware of the existence of the little girl from other people’s stories, one who would be her own age, and also to the possibility of her understanding the cry of adultery as she understood the cry of love in the garçonnière that she shared with her lover. He says: “Who knows… Maybe she cried with him, and after crying came love.” Maybe that would comfort him too. The clip concludes with her returning to ignorance of what happened, “The little girl never knew about those events.”

Or is it just a laconic and resigned facade of lack of knowledge when that is the norm The intuitive knowledge of your unlimited loving influence? Certainty and uncertainty are interchangeable.

The doubt imposed by reality—she was not there, and could not have known what was happening—is replaced by the conviction of knowing that she is the only recipient of desire and the only one capable of making delegated desire possible. A superiority capable of compensating for her real exclusion: she is white, but the superiority she enjoys in the eyes of her mother and siblings, despite her poverty, does not apply to the lover’s father: belonging to the same culture as him and “the equality of their fortunes,” as the North Chinese lover would say—which also underlies this novel—were the non-appealable requirements for her son’s marriage preference.

There is another kind of uncertainty running through the story, another question: Did the little girl love the Chinese man? We know it’s her yes. There are details about this love. Instead, she claims she didn’t love him, whether we believe her or not.

However, in a passage that briefly precedes these endings – during her boat journey across the ocean, when the waltz that Chopin had never learned sounds, when she wanted to commit suicide by throwing herself into the sea – like that boy whom she vaguely recalls and whose death she heard in Sadik (there is also more than one version of this fact in the novel) – she raises this doubt with a double negation and expression of the final past: “…she thought of the man from Chulin, and she was not sure, suddenly she did not love him with a love which would have gone unnoticed because it had been lost in History is like water in sand, and he only knew it now, in this moment of music that sounded across the sea.

Perhaps it does not matter much to practice responding to a text in which what is not said, or what is not implied, constitutes the greatest pleasure in reading. It doesn’t matter that the narrator suggests it Beloved Because this man is neither the man in the War Notebooks (the autobiographical testimonies in which Duras describes the genesis of his texts) — with whom she once slept, who was sometimes repulsive and who was only fascinated by his gestures of economic power — nor the man from northern China (Northern China lover(a different version of the lover’s story from 1991), to whom he says “the words of books and movies and all lovers… I love him” and to whom he cries after the phone call with which both novels end, long after the end of his story.

* Professor of Arts (UBA), Master and DEA from Sorbonne University