Among the hundreds of cemeteries in Armero, a municipality in Colombia, in the department of Tolima, most visitors pass right by.

They make a pilgrimage to the tombstone of Omera Sánchez, the girl who 40 years ago became a symbol of the tragedy that ended the city and the lives of 20,000 residents of Armero.

Another 5,000 people died in municipalities surrounding the city, located about 160 kilometers east of Bogotá.

On November 13, 1985, the Nevado del Ruiz volcano in Tolima Province erupted. Its flows melted 10% of the ice sheet and descended the slope containing sediments, rocks and clay.

The torrent destroyed Armero, and the victims died, crushed by rubble and suffocated by mud.

Amira, 13, was trapped up to her neck. With the support of a branch, with the help of rescuers, and journalists filmed her 60-hour ordeal, which was broadcast live.

The girl told the cameras: “Mom, if you listen to me – I think so – pray that I can walk and that these people will help me.”

Without specialized machinery and in the chaos, rescue was impossible.

Four decades later, Amira’s tomb is the most visited place in Armero – today a cemetery of monuments and tombs braving the tall grass.

Hajj Centre

A few meters from the grave, local merchants sell souvenirs. It is a strategic point because thousands of people pass through it every year.

Visitors pray, take photos, give thanks, and leave offerings; They venerate Amira as a saint.

“She was very brave,” says Gloria Cartagena, a resident who frequents the memorial. “I trusted her to be saved until the end. People say she works miracles.”

Ricardo Solorzano also comes every month. Before her death, five years ago, his wife, an Armero resident, requested that her ashes be scattered there.

“I came because the girl gives me the courage to continue living and peace of mind,” says Solorzano. “Any honor (for Amira) is more than deserved. She is an angel.”

“Thank you, Omerita, for granting me the miracle I asked of you,” says a stone slab near the grave.

Another message read: “Thank you, Omira, for the services you received.”

So many letters had accumulated around the tombstone that a few years ago they decided to surround it.

There are three other monuments dedicated to offering offerings and prayers, also around his supposed place of death.

Today, the place is unrecognizable, but years ago the street was where the Sanchez and Garzon family, the O’Meara family, and their neighbors the Galiano family lived.

“We thought it was the end of the world”

On the day of the tragedy, Amira’s mother, nurse Aleida Garzón, was in Bogotá to solve some cases.

The girl stayed at home with other family members. They were probably already asleep, like many in town, including Marta Galeano, Garzón’s neighbor and co-worker.

Galeano says she was frightened that night, disoriented by the flashing of fireflies.

Minutes later, he realized that those lights were not insects, but rather the flashlights of neighbors who were fleeing the avalanche.

She remembers that she woke up her husband, that they walked with their two children to a high point in the city, and that on the way they passed over dead people.

I heard no more about Amira until I saw her in pain on television hours later.

“I couldn’t believe it. We don’t forget a horror like this. Such a well-behaved Catholic girl, who enlivened the community with dances,” Galeano reflects in a conversation with BBC News Mundo, the BBC’s Spanish-language news service.

He adds: “Many years have passed, but we still remember it today.”

Armero had a population of about 29 thousand people before the disaster. It was a prosperous city, and the cotton industry was flourishing there.

Today, many of the survivors live in neighboring municipalities, such as Honda, Lleida or Armero Guayabal, where Galeano welcomes me.

Months before the tragedy, many experts in Colombia warned of the threatening activity of the volcano and the danger it posed to municipalities such as Armero, but there was no effective response by the authorities.

In addition to nearly 25,000 deaths, the disaster destroyed more than 5,300 homes and affected nearly 230,000 people.

In the absence of scientific and political explanations, faith provides an answer to the sufferings of people like Galeano, Garzón, and thousands of pilgrims.

“We thought it was the end of the world, and the girl, Amira, was destined to become an angel and a story of courage,” says Galeano.

“May God allow her to be canonized one day,” says Aleida Garzón, Amira’s mother, who currently lives in Lleida, 15 kilometers south of the site of the tragedy. “She is my angel, my guardian, my warrior.”

distraction

Not all Armero survivors agree on how Amira’s memory was used by merchants, press, and visitors.

Garzón, who frequently visits her daughter’s grave to keep her safe, doesn’t seem entirely satisfied with the fact that tour guides read the girl’s words before her death or even present themselves as family acquaintances without being one.

“Some people save the story on TikTok and then charge you for the tour,” he says.

Maria Moreno, who runs the souvenir stall, makes more money in seasons when there are more visitors, such as this period in November before the anniversary of the tragedy.

She agrees that her work is in the best possible shape, as the girl’s grave is the busiest place in Armero and where visitors spend the most time.

He says he feels “sad” because his livelihood comes from this tragic story, but he has no alternative: “I wanted to get out of this, but now it’s not possible.”

Some also lament that the attention the Amira monument has received takes the focus away from Armero’s overall situation.

The family of Gloria Cartagena, a regular visitor, points to the plastic bottles and waste others throw on the ground.

“They have put up more signs honoring the victims and commemorating what happened on some roads, but it is sad to see the state of many of the remaining cemeteries and buildings: vandalized and full of graffiti,” Cartagena says.

Many bodies were not recovered. Some empty graves mark the last place where victims were seen or where they supposedly lived.

There are people who, days before their birthday, paint and repair their own epitaphs. Others appear to have been abandoned for years.

On some of the houses still standing, cut off by tree roots or half-buried, are painted the names of the families who lived there.

In the old cemetery, almost all the graves appear to have been vandalized. There are isolated bones within some of the niches.

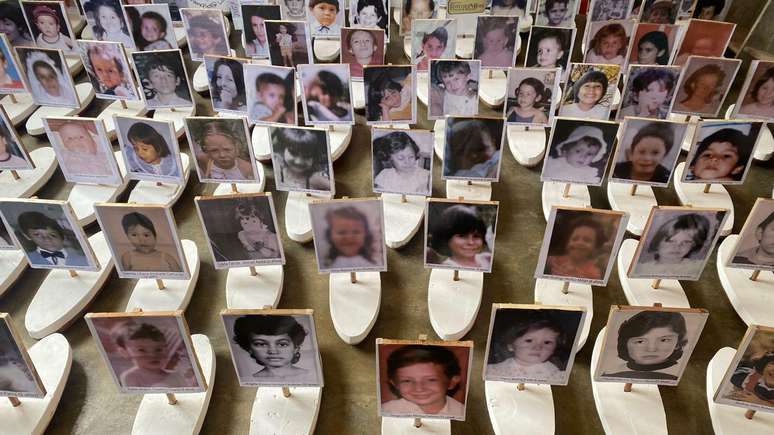

Armero’s other children

Many survivors of the tragedy feel that the state’s abandonment of Armero is not just a physical abandonment.

And that the great media exposure of the Omera Sánchez case occupies too much space in the press and among visitors, without paying due attention to the drama of the other “Armero children”.

This is the position of Francisco Gonzalez, director of the Armando Armero Foundation, dedicated to reconnecting family members separated during the tragedy and rebuilding the memory of the municipality.

Armando Armero denounced the placement of about 500 children for adoption through “regular and irregular processes.”

Many of them, now adults, live in Colombia. Others ended up abroad.

Gonzalez believes some don’t even know their roots.

The Colombian Institute for Family Welfare (ICBF) says that due to gaps in legislation at the time, it was necessary to investigate the irregular operations reported by those affected on a case-by-case basis.

ICBF Director Astrid Cáceres confirmed to BBC News Mundo that they would intensify efforts to recover memory and clarify adoption cases with the victims.

Through Armando Armero, 400 families and 75 registered adoptees have undergone DNA testing.

To date, four reunifications have been made through genetic comparison.

Hundreds of victims still wait, every anniversary, for their family members to appear again at a memorial event.

Hajjaj Amira – and hundreds of other Armero children – share a fixation on miracles.