The original imprint of Brazilian concrete – which appeals to the metaphor of food and digestion, to continue thinking about the national – offers a radical version to address the question of influences.

Tarsila do Amaral was perhaps the most representative of the modernist movement in her country. She composed 272 paintings, six murals, and about 1,300 drawings. He worked in the workshop of the Swedish sculptor William Zadig and in the following years studied drawing and painting with the academic teacher Pedro Alexandrino and later with the German artist Georg Elbons. Tarsella’s initial output was limited to animal studies or still lifes and photo sketches, which she compiled in notebooks.

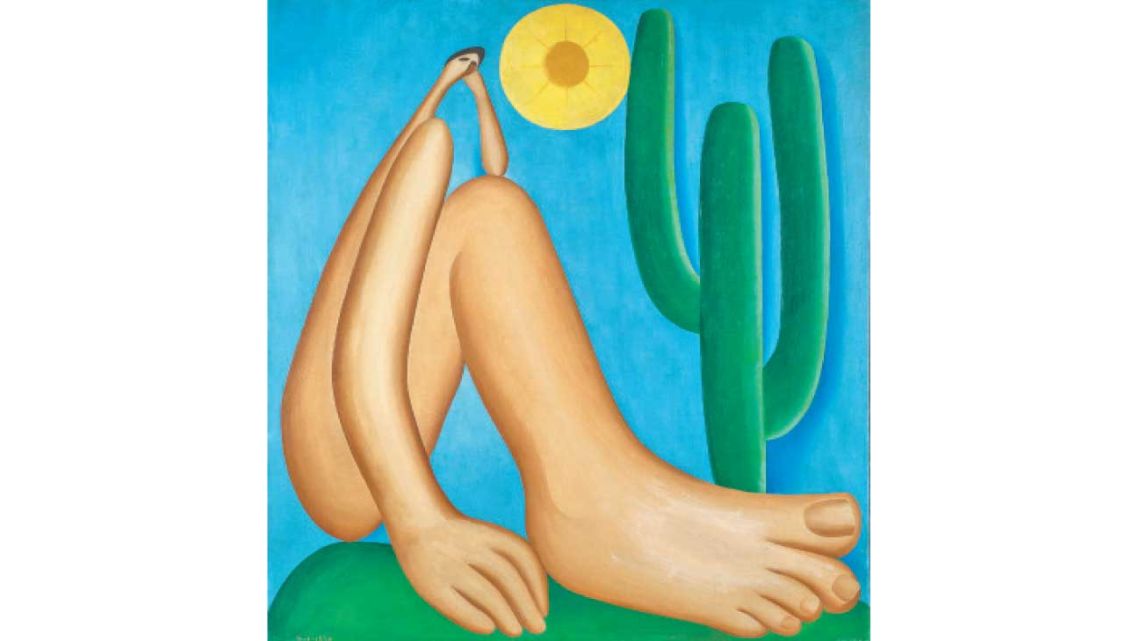

In 1928, Tarsila do Amaral gave her husband, Oswald de Andrade, an ababoro for his birthday, a name of Tupi-Guarani origin that means “the man who eats.” The symbolic work that excites the senses that the Anthropophagus Manifesto will later bear is an oil painting on canvas representing a stylized human figure with exaggerated proportions (small head, large limbs) next to a sun and a cactus, symbolizing the idea of “swallowing” and transforming European culture into something of its own.

Authoritarians don’t like this

The practice of professional and critical journalism is an essential pillar of democracy. This is why it bothers those who believe they are the bearers of the truth.

In this way, Brazilian modernism was shaped to be a summary of its era, a diagnostic and therapeutic synthesis for understanding the changes experienced by Latin American countries in the last century. When asked who eats whom? That is, who are we? Andrade answers with something like what we eat: “Only anthropophagy unites us. Socially, economically, philosophically.” For this reason, Ababoro returns as a sign and a mystery. The composition of this present of exchanges, boundaries, closures, interventions and new leaderships.