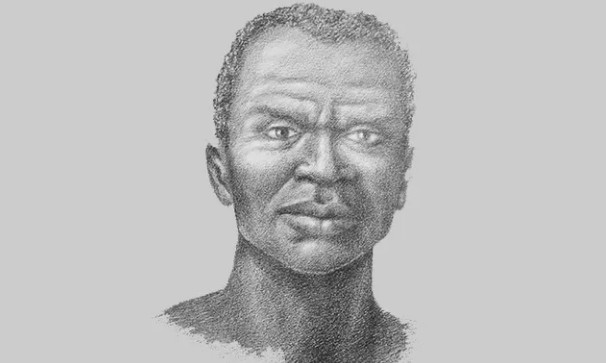

Zombie dos Palmeiras was still a little-known historical figure outside academia. On the night of November 20, 1971, about 20 people gathered in a room at the Clube Náutico Marcílio Dias, in Porto Alegre, to honor the Quilombola leader who died in 1695. At that time, there was no idea of turning the date into a holiday, but the meeting at the club could be considered ground zero. A mobilization that spread across the country and led to the creation of Black Awareness Day, which is celebrated today throughout Brazil.

- Abdias do Nascimento: “The genocide of blacks was a constant in the construction of Brazil.”

- Leah Garcia’s role: The actress changed the script for Zombie dos Palmares in a 1980 TV series

Mobilization began in July 1971, when activists from the black gaucho movement created the Palmares group “to promote studies on history, the arts and other aspects, in particular with regard to black and mixed-race people of black descent,” according to the entity’s statute. During the period of the military dictatorship, when the myth of Brazilian racial democracy was in effect and there was no room for appeal, the suggestion was to carry out activities to glorify black figures who did not receive due attention.

- Instagram: Follow our profile, with images from one hundred years of journalism

Among the founders of the Palmares group were activists such as Elmo da Silva, Velmar Nunes, Antonio Carlos Cortés, and the poet and professor Oliveira Silveira. Silveira came up with the idea of setting November 20, the day of Zombie’s death, as a milestone to celebrate black history, in contrast to the then undeniable May 13, the date of Princess Isabel’s signing of the Lei Áurea Charter, in 1888.

/i.s3.glbimg.com/v1/AUTH_da025474c0c44edd99332dddb09cabe8/internal_photos/bs/2025/m/4/sOBHQNSgyDbNrnERs97g/grupo.png)

A high school teacher of Portuguese language and literature, Silveira has written ten books of poetry, including “Banzo, saudade negra” (1970), which received an honorable mention from the Brazilian Writers’ Union. The author also published articles and records in the press and participated in various groups. In 2011, two years after his death from cancer, the literary collection of the Palmares Foundation, an organization linked to the Ministry of Culture, was named the Oliveira Silveira Library.

From the beginning, members of the Palmares group have taken advantage of events to celebrate names in Afro-Brazilian history who deserve more recognition from the community. In August 1971, for example, they held an event to commemorate the 89th anniversary of the death of the abolitionist lawyer and self-taught intellectual Louise Jama. Journalist José de Patroceño, another voice against slavery in the 19th century, was honored on October 9, his date of birth, 1853.

Discomfort over the May 13 celebration, centered on the figure of Princess Isabel, was at the heart of the mobilization in Porto Alegre. The group felt that this landmark ignored the history of the black freedom struggle well into the 19th century and the glory of the aristocrat who, as we know today, had nothing to do with the abolitionist cause. Hence the idea of commemorating Zumbi, the last leader of Quilombo dos Palmares, the largest quilombo in the colonial period.

/i.s3.glbimg.com/v1/AUTH_da025474c0c44edd99332dddb09cabe8/internal_photos/bs/2025/t/A/guYnDRQrqYrn4B5NsgEA/oliveira.png)

The stronghold of black resistance in colonial Brazil, located in Captain Pernambuco, in the area of present-day Alagoas state, Palmares was, in fact, a kingdom with several quilombo formed by former slaves who had escaped from plantations and slave quarters and sought refuge in the Serra da Pareja. It is estimated that in the middle of the seventeenth century its population reached 30 thousand people.

To understand zombies, Silveira studied books such as “Quilombo dos Palmares” by Edson Carneiro, and “As Guerras nos Palmares” by Ernesto Ines. The poet realized that historiography did not precisely determine the hero’s date of birth, but he found data confirming that on November 20, 1695, years after the battle, he was killed by local government soldiers. His head was displayed in a public square in Recife to dispel the myth of Zombie’s immortality.

/i.s3.glbimg.com/v1/AUTH_da025474c0c44edd99332dddb09cabe8/internal_photos/bs/2025/v/a/DGDWooQHK6UP76s18tyw/quilombo.png)

The meeting at Clube Marcílio Dias was announced in the press, prompting the Federal Police to summon the participants to testify. In 1971, Brazil was experiencing the harshest period of military dictatorship. The repressive bodies closed their doors to armed struggle. Some say agents confused the Palmares group with VAR-Palmares, a major guerrilla organization. At the police station, Oliveira and Carlos Cortes had to convince the police officers that they were not “terrorists.”

Thanks to a movement that began in Porto Alegre, more than half a century ago, the Zombie Death Date stimulated demonstrations, meetings, parties and parades in several cities in Brazil over the years, until it was finally adopted as Black Awareness Day, in 1995. In 2003, this important event was included in the national school calendar, and in 2011, Law No. 12519 officially established the National Zombie and Black Awareness Day. Today, the date is a holiday throughout the country.

/i.s3.glbimg.com/v1/AUTH_da025474c0c44edd99332dddb09cabe8/internal_photos/bs/2025/b/L/fQUG14RseqpfZ2v7MA3Q/passa.png)