Image source, Getty Images

-

- author, Dario Brooks

- Author title, BBC News Mundo @ Hay Arequipa Festival 2025

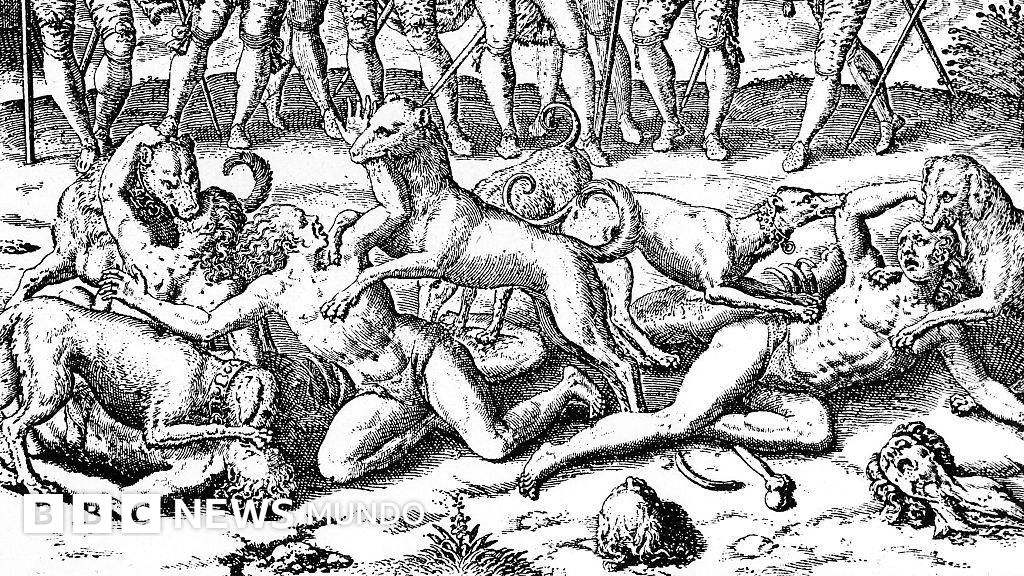

To control pre-Hispanic peoples about 500 years ago, Spanish explorers had a weapon brought from Europe that was as terrifying as swords, bows, cannons, and horses: dogs.

Many of the Spanish Crown’s expeditions brought with them specimens of the imposing breeds, such as the Spanish Alano or the German Bollenbeiser, not only for use in the protection and control of missions or settlements, but also in attack against the natives.

In the case of the advance against the Inca Empire, dogs were part of a strategy to terrorize the local population, who, although they knew smaller, friendlier breeds of that animal, were astonished to see herds with such an aggressive instinct.

“The dog becomes a weapon. There were whole logistics around the size of the dog, its training and the soldier who was in charge of it,” writer and Peruvian army colonel Carlos Enrique Frere tells BBC Mundo.

His latest novel, Land of Canes, follows one of the “enforcers” responsible for training and guarding the herds of the Spanish contingent in their campaign for the Spanish takeover of Peru.

The work is on display at the Hay Arequipa 2025 festival, which takes place in the Peruvian city from November 6 to 9.

Leoncico and Piccirillo

There is little literature on the presence of dogs among the Spanish ranks and only some representations in the art of the time.

Freire says that he addressed this topic while traveling to the Peruvian city of Tumbes, the capital of the region of the same name, located in the northwest of the country, where he reviewed the writings of some historians of the time such as Juan de Betanzos or Bartolomé de las Casas, both Spaniards who delved into indigenous cultures and even described the abuses of conquest.

The writer explains: “They talk about these dogs and give them names, often with their characteristics.” “The dogs arrived in Tumbes and exterminated the existing population.”

Image source, Getty Images

In his fantasy novel based on historical events, Thomas de Cherez becomes a trainer for a majestic dog called a domero. But since the first explorations of America, the military leader Vasco Nunez de Balboa had dogs, including a Spanish dog named Leoncico.

This was part of the litter of another majestic dog, Picerrillo, which had been owned by military leader Juan Ponce de León since his advance on the island of Hispaniola and what is now Puerto Rico.

“Vasco Nunez de Balboa’s relationship with his dog Piccirillo was very deep,” says Freire.

“There is a scene – it happened in real life – in which he goes to see the Pacific Ocean for the first time. He reserves the right to see that sea for the first time and to do it with his dog. He has left all his officers and troops behind,” the writer explains of what he discovered while researching his novel.

“It made me see the strong connection that existed between the two dogs,” he concludes.

Dogs have been valued since those early times of exploration and control of Native American lands in the first half of the 16th century.

Image source, Getty Images

Weapon of war and punishment

While exploring the Amazon, the Spanish took as many as 2,000 dogs. Francisco Pizarro was one of those who led the raid that ended in the overthrow of the Inca Empire. One of the first points he passed through was Tumbes.

“They did not have as many horses as is thought,” explains Fryer, “and firearms were very limited compared to those we know today.” “Where a weapon, a sword, or a horse cannot enter, a dog can enter.”

It was unleashed by bulldogs against indigenous people who did not know large, attack-trained dog breeds such as those brought from Europe.

“These Spanish dogs were huge,” he explains. “An animal that eats meat gets bigger, and these breeds had been worked on beforehand. So what they (the indigenous people) saw was a lion, not a dog.”

“Their job was to be war dogs.”

Image source, Getty Images

The use of enclosures was not limited to the subjugation of the Inca Empire, but was a common practice in many areas of the Caribbean and Mesoamerica and in the territories of Mesoamerica, including the people of Mexico.

Dogs were used to intimidate resisting indigenous people and inflict punishments.

“In the middle of the sixteenth century, Coatl de Amitatan was sentenced to death by stoning and burning for practicing incense and idolatry, for invoking demons, for not keeping or wanting to preserve the objects of faith or respect for the Christian faith, for neglecting the cleanliness of the church and for commanding the Indians of his city not to attend the faith,” reads “The Magnificent Master Alonso Lopez, Mayor of Santa María de la Victoria and Rounder of the Indians,” a book edited by the National Autonomous University of Mexico.

Historian Miguel León Portela even rescues stories from the indigenous people of what is now Mexico in his book The Fate of the Word.

“And their dogs are very, very large: they have ears folded many times over, and great trembling jaws; they have bulging eyes, eyes like embers; they have yellow eyes, fire-yellow eyes; they have thin bellies; ribbed bellies, skinny bellies; they are very big, they are not quiet; they trot panting, and their tongue hangs out; they have spots like a jaguar, they have spots of different colours,” says a story in Nahuatl. language.

He explains that Freire sought to center “Tierra de Canes” in Peru “to prevent the story from flowing.” He believed that the crude old stories should be toned down.

The author says: “The use of violence in the text is descriptive, but it is not enough to make people close the book and say: ‘How ugly.’ There had to be some balance.”

Image source, Getty Images

Give up

After controlling the territories and population, dogs lost their main benefit and over time became a nuisance to the Spanish.

Since they needed labor, including enslaved labor, further elimination of the indigenous population was not an option, and the presence and aggression of dogs began to be a nuisance.

Freire explains that letters were sent from the Crown in Spain asking the various leaders in America to get rid of the dogs to avoid further trouble, even against the Spaniards themselves.

The writer says: “They saw that leaving them at large led them to form groups that eventually ended up fighting the Spaniards and the indigenous people. This is why the queen’s orders appeared regarding harming dogs.”

However, over the years and fights together, the aperreadores create a special bond with their dogs, and vice versa, which also reflects the plot of “Tierra de Canes”.

“It’s a very close relationship between the dog and the soldier who carried him,” says Freire.

As a result, it was unthinkable for some patrons to get rid of their favorites despite royal decrees.

As Spanish rule consolidated in indigenous lands, dogs began to lose their character as weapons of war, and the memory of them being one of the keys to the enslavement of indigenous peoples began to fade.

Little by little her job became more focused on protection and accompaniment. Only some like Becerrillo or Leoncico have survived in memory.

Image source, Alfaguara

Subscribe here Join our new newsletter to receive a selection of our best content of the week every Friday.

And remember, you can receive notifications in our app. Download the latest version and activate it.