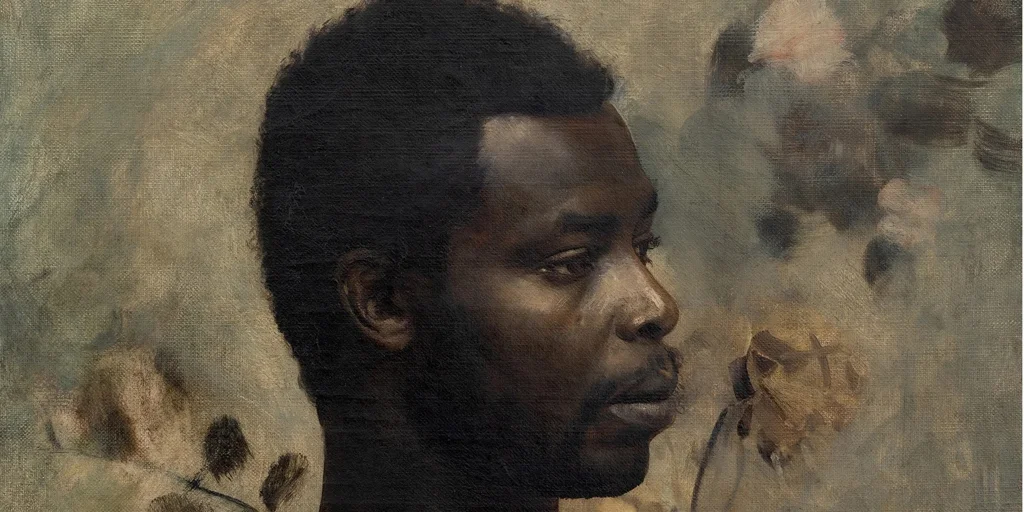

In 2021, two Vienna-based collectors went to W&K-Wienerroither & Kohlbacher Gallery From the Austrian capital was presented a poorly framed and very dirty painting, with the seal of succession barely visible, by Gustav Klimt. The expert in … The artist Alfred Weidinger, author of the catalog raisonné published in 2007, quickly identified the painting as the lost portrait of an African prince, an important representative of the Osu (Ga) of Ghana, which he had been searching for for two decades. Botanical elements appear on the back. Weidinger explains that the image has a special meaning: “The composition and pictorial execution indicate Klimt’s tendency towards decorative elements, which would characterize his later works, and are directly related to his innovative images in the following years. In terms of time and style, it is close to the famous 1898 portrait of Sonia Knips.

In 1897, Gustav Klimt and his colleague Franz Mach may have contracted Ashanti fever. Like up to 10,000 Viennese every day, they both made a pilgrimage to the Prater River to enjoy the so-called “Ashanti” (actually people from the Osu or Ga tribe of Ghana) at one of the popular places “Völkerschauen” (human zoos) At that time in Tiergarten am Schüttel. These were displays of indigenous peoples stigmatized as “savage” or “exotic” in zoos and amusement parks or at world and colonial expositions in Europe, the United States, and Japan from 1875 to the 1930s. In the nineteenth century they were very successful.

Both painters were particularly interested in the chief of the Osu tribe Prince William Ni Norte Douna. Klimt painted him in profile, while Franz Mach depicted him almost frontally. Much’s more traditional portrait is currently in the Luxembourg Museum.

Klimt’s painting remained in his hands even after his death It was auctioned at the S. Kende Hall in Vienna in May 1923 Such as “Portrait of a black man, three-quarter profile, facing right, white coat over his shoulders.” In 1928, it was loaned to the artist’s memorial exhibition of the Vienna Secession. It was royalty Ernestine Klein. She and her husband Felix converted Klimt’s former studio in Vienna’s Hitzing district into a home. The marriage was huir in 1938 due to his Jewish origin. They survived the war in Monaco. However, his artwork disappeared, including the image of the African prince.

After restoration of the painting and intense negotiations, an agreement was finally reached. Redemption agreement with the heirs of Ernestine and Felix Klein. Federal Antiquities Office Agreed to be exported. The image was scheduled to be shown in the TIFF 2024 edition, but legal problems arose that prevented this. However, this year he went to the show and was the star of the W&K-Wienerroither & Kohlbacher show. It was his wreck 15 million euros.

Vienna Prosecutor’s OfficeHe ordered the painting to be confiscated By Gustav Klimt at the request of the Hungarian authorities, who claim that the work was Exported irregularly Local public broadcaster ORF reported that Hungarian authorities suspect the owner concealed that the painting was a Klimt work during the export licensing process. The seizure adds a new chapter to the painting’s already complex history. The canvas remained in Hungary for about five decades. In May, Hungarian newspaper HVG reported that Hungarian authorities may have improperly authorized the export of the painting.

The painting had been in Hungary since 1938, where it was brought by the Klein family, its owners, who had fled the Nazis. However, it was not returned to the family because its Hungarian owners had not done so, but this did not change ownership; In Hungary the owners were only guardians. Austrian newspaper Der Standard claimed earlier this year that the Hungarian Ministry of Construction and Transport had mistakenly allowed the work to be exported, claiming it had no particular value. According to the newspaper, paintings that do not belong to their author require an export permit if they are more than 50 years old and their value exceeds one million Hungarian forints, equivalent to about 2,500 euros. Authorities may not have discovered the stamp indicating that the painting came from the estate of Gustav Klimt.

Zofia Vijvary of the Budapest laboratory noted in a blog post about her work on the plaque that the heritage seal is there, even if it is not easy to see, and that The artist’s name appears on the wooden frame; The latter, he says, can only be seen under infrared light.

HVG reported that the Hungarian agency denied issuing an export permit. However, Der Standard claims to have reviewed the statement issued on 21 July 2023 by the Austrian Federal Archaeological Office, which was provided to the newspaper by both the office and the gallery.

A spokesman for the Wienerroither and Kohlbacher gallery stated that the painting was examined by Hungarian authorities in 2023 and declared safe. “This allowed it to be exported,” he said in an email. A scanned copy of Hungary’s official confirmation, seen by Artnet News, indicates that “no export license is required.” It is now up to Hungary to prove that the painting was illegally taken out of the country. In this case, the painting must be returned, and since it is a protected work, it cannot leave the country.