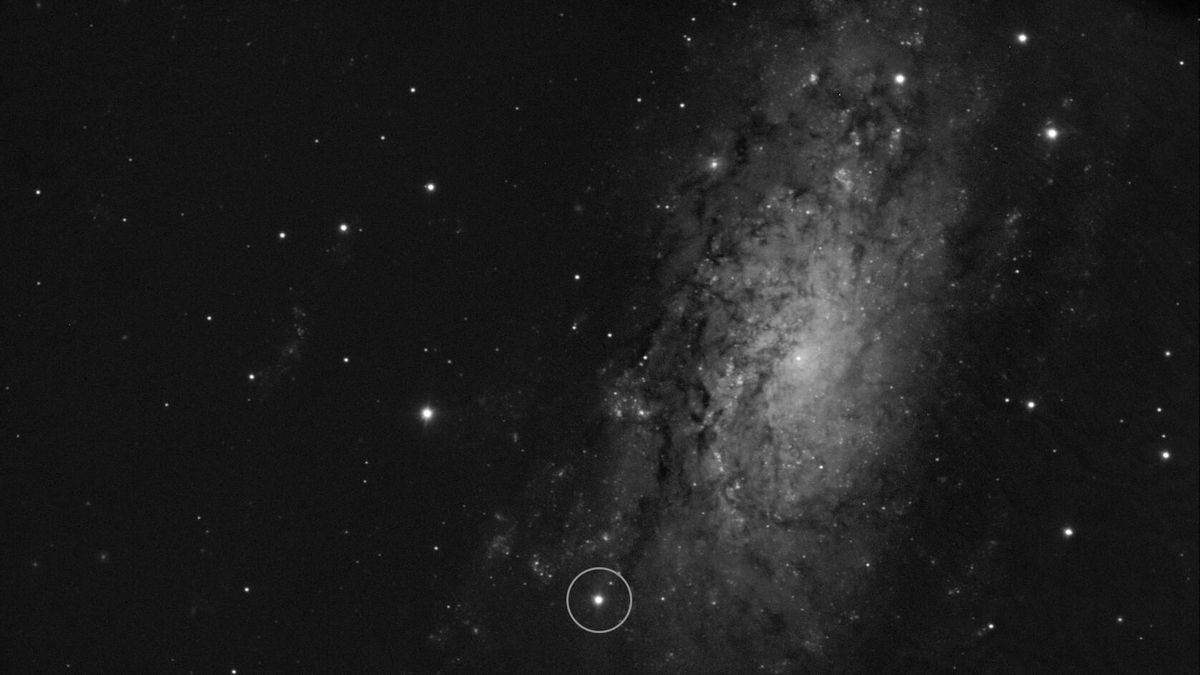

An international team of astrophysicists has observed for the first time the first and most fleeting phase of a supernova, an exceptional circumstance that allowed us to know the details of the death of this type of star in a huge explosion. Thanks to a series of quick notes with Very large telescope (VLT) which will be published this Thursday in the magazine Advancement of scienceScientists have documented how the initial explosion was shaped like an olive, and later flattened out to eject material into the cosmic vacuum.

Large telescopes typically target supernovas after a critical few hours have passed since their initial detection, and the explosion has already dispersed matter and surrounded the dying star. On this occasion, the team of Yi Yang, an assistant professor at Tsinghua University in Beijing, China, had responses to a request for a quick observation of that region of the sky using VLT, on the night of April 10, 2024.

When the SN 2024ggi supernova explosion was discovered, Yang had just landed in San Francisco after a long flight and knew he had to act fast. Twelve hours later, it submitted an observation proposal to the European Southern Observatory, which, after a very quick approval process, pointed its VLT telescope in Chile at the supernova on April 11, just 26 hours after the initial detection.

Accelerated matter

Supernova SN 2024ggi is located in the galaxy NGC 3621, in the direction of the Hydra constellation, just 22 million light-years away. Using a large telescope and the right instrument, the international team knew they had a unique opportunity to reveal what the explosion looked like shortly after it occurred. “The first VLT observations captured the phase during which matter due to the explosion near the center of the star accelerated through its surface,” says Dietrich Baade, an astronomer at ESO in Germany and co-author of the study. “For a few hours, the geometry of the star and its explosion can be observed together.”

The first VLT observations captured the phase during which material accelerated by the explosion near the center of the star passes through its surface

Dietrich Bade

— An astronomer at ESO in Germany and co-author of the study.

This moment is crucial, because once the shock wave passes through the surface, it releases huge amounts of energy; The supernova shines so bright that no details can be observed. During a short-lived phase, the initial “disintegration” form of the supernova can be studied before the explosion interacts with the material surrounding the dying star.

“The geometry of the supernova explosion provides fundamental information about stellar evolution and the physical processes that lead to these cosmic spectacles,” Yang explains. The exact mechanisms behind supernova explosions of massive stars, those with masses more than eight times the mass of the Sun, are still debated and are one of the fundamental questions scientists want to solve. This supernova’s predecessor was a red giant star, with a mass between 12 and 15 times the mass of the Sun and a radius 500 times larger, making SN 2024ggi a classic example of a massive star explosion.

“Disintegration” of the star

We know that during its life, a typical star maintains its spherical shape as a result of a very delicate balance between the force of gravity, which tends to compress it, and the pressure of its nuclear drive, which tends to expand it. When the last fuel source runs out, the nuclear engine begins to fail. For massive stars, this marks the beginning of a supernova: the dying star’s core collapses, and the surrounding layers of mass on top of it fall and bounce back. This shock wave propagates outward, causing the star to disintegrate.

Astronomers were able to observe the initial “disintegration” form of the supernova for the first time using a technique called spectrophotometry, which provides information about the geometry of the explosion that other types of observations cannot provide because the angular scales are so small, according to co-author and professor at Texas A&M University in the US. Although the exploded star appears as a single point, the polarization of its light contains hidden clues about its geometry, which the team was able to decipher.

These results point to a common physical mechanism that leads to the explosion of many massive stars, which exhibit well-defined axial symmetry and operate on a large scale.

Yi Yang

— Professor at Tsinghua University in Beijing and lead author of the study

To do this, they used the FORS2 instrument, mounted on the VLT, which revealed that the initial explosion of material was olive-shaped. As the explosion spread outward and collided with the material surrounding the star, the shape became flattened, but the axis of symmetry of the ejected material remained the same. “These results point to a common physical mechanism that drives the explosion of many massive stars, which exhibit well-defined axial symmetry and operate on a large scale,” asserts Yang.

With this knowledge, astronomers can now rule out some existing supernova models and add new information to improve others, providing insight into the powerful death of massive stars. “This discovery not only redefines our understanding of starbursts, but also demonstrates what can be achieved when science pushes the boundaries,” says co-author and ESO astronomer Ferdinando Patat. “It is a powerful reminder that curiosity, collaboration, and quick action can reveal profound insights into the physics that shape our world.”

“Amazing job”

Miguel Torres, an astrophysicist at the Institute of Astrophysics of Andalusia (IAA), considers it “an amazing and valuable work” with results that have a major impact on the physics of supernovae formed as a result of the collapse of the nucleus (types Ibc and II). He asserts: “If the European Southern Observatory had not given them time and had not reacted immediately, this knowledge would not have been obtained.”

If ESO had not given them time and responded immediately, this knowledge would not have been obtained

Michael Torres

— Astrophysicist at the Institute of Astrophysics of Andalusia (IAA)

For the expert, these studies of polarized light a few hours after the supernova explosion have put the final nail in the coffin of explosion models that still talk about spherical symmetry. “The preferred model seems to be one that invokes magnetic rotational processes, where the amplified magnetic field carries material along the spin axis of the collapsing core,” Torres says.

Junay Gonzalez, a researcher at the Institute of Astrophysics of the Canary Islands (IAC), highlights the great value of having observations of the supernova from almost the first moment until approximately 200 or 300 days after the explosion. “In this case, using a technique called spectrophotometry, they obtained information about the geometry of the explosion in three dimensions,” he points out. “Thanks to this, they can understand how the explosion was directed, and from there extract information about how it occurred.” He points out that the exact mechanisms by which star collapse and the production of an external wave front are stopped are still not known in detail.

By reconstructing the 3D geometry of the first hours of the starburst, they were able to see that in this case it was an asymmetrical explosion

Louis Galbani

— Astrophysicist at ICE-CSIC

Louis Galbani, an astrophysicist at ICE-CSIC, believes we are facing an exceptional observation. “The scientific goal was to analyze the geometry of the star, which was initially spherical, immediately after the collapse and expulsion of matter,” he says. It was unknown whether the explosion developed symmetrically, retaining the same spherical shape of the star, or, on the contrary, followed a preferential (olive-shaped) axis.

“By reconstructing the three-dimensional geometry of the first hours of the stellar explosion, they were able to see that in this case it was an asymmetric explosion,” the expert says. “This does not mean that all supernovae are like this, but it contradicts the theoretical idea that all explosions are perfectly symmetrical.” In short, Galbani concludes, “This discovery changes our understanding of how massive stars collapse and how the heavy elements that enrich the universe are distributed.”