José Gabriel Condorcanqui Nogueira He was born on March 19, 1738 in Surimana Province Cuscowithin the Coracas family she descends from the latter Inca Vilcabamba. By patrilineal inheritance, he took over the chiefdoms of Surimana, Pampamarca, and Tungasuka, giving him a position of leadership in the indigenous world and before the colonial authorities. He received a thorough education at the Jesuit-run School of San Francisco de Borja in the Imperial City, where he learned Spanish, Quechua, and Latin, and came into contact with the enlightened ideas that were sweeping Europe and beginning to seep into America.

This combination of lineage, instruction, and local leadership was unusual at the time. From a young age, Kondorkanke emerged as a mediator between his communities and the colonial power, making frequent demands for relief in taxes and mining taxes, as well as denouncing abuses committed by officials and judges. However, their complaints submitted to the judges and at the request of the Crown Prosecution Service itself were systematically ignored.

In the middle of the eighteenth century, Bourbon reforms The opening of new trading circuits (such as the opening of the port of Buenos Aires) also increased financial and economic pressures on indigenous peoples and traders in the southern Andes. Conditions of excessive exploitation, extortion of tribute, forced labor in mines (mita), and abuse of the character of chiefs turned the lives of thousands of indigenous people into a daily ordeal. Added to the structural oppression is the arbitrariness of the system of distribution of goods, taxes, and workshops.

Faced with the indifference of the colonial authorities, Kondorkanke realized that the legal path had reached its end. The search for justice is no longer possible through petitions or actions, but through rebellion.

On November 4, 1780, Condorcanqui’s life and the history of Peru changed forever. After the arrest and execution of Tinta’s mayor, Antonio de Arriaga, accused of repeated abuse and extortion, Tupac Amaru II – a new name he adopted in honor of his ancestors – issued a call for rebellion. The movement spread rapidly throughout the southern Andes, Upper Peru, and the Río de la Plata region.

In contrast to later independence struggles, Túpac Amaru II’s initial goal was not final separation from the Spanish crown, but rather the end of practices such as the mita, obrajes, the patch system, arbitrary collection of taxes and customs, and forced distribution of goods. In an unprecedented gesture in Latin America, on November 16, 1780, he issued a statement abolishing black slavery. “I prohibit the slavery of black people.”He ordered, anticipating that the death penalty would be abolished in other parts of the continent by several decades.

The rebellion achieved its first great victory in… Battle of Sangarara (November 18, 1780), where the rebels eliminated the royal forces led by Tiburcio Landa. Despite the momentum of his victory, Túpac Amaru II chose not to immediately head for Cuzco, which facilitated the reorganization of the Viceroy’s defense and the arrival of reinforcements from Lima and Buenos Aires.

The movement began a two-month siege, but failed to break internal resistance, partly due to divisions and the absence of a more coordinated military strategy. The Viceroy’s repression intensified with the arrival of an army of 17,000 men led by the visiting José Antonio Ares and Viceroy Agustín de Jauregui.

On April 6, 1781, after defeat at Chicacope and the victim of betrayal by those close to him, Túpac Amaru II was taken prisoner. He was chained, severely tortured, and taken to Cuzco.

On May 18, 1781, José Gabriel Condorcanqui was publicly executed in Cusco’s Plaza de Armas, after watching his wife, Micaela Bastidas, his children, and his followers die. The unusually cruel punishment was intended to instill terror: his body was mutilated and distributed in neighboring towns as a lesson.

The rebellion was not put down, but continued under the leadership of other leaders, such as Diego Cristobal Túpac Amaru and Túpac Catari in Upper Peru, who came to besiege La Paz for several months. In parallel, the colonial response erased indigenous symbols: it banned the Quechua language, local clothing and any reference to the Inca past. Despite the repression, the movement left an indelible mark both on the region and subsequent struggles.

The rebellion of Túpac Amaru II became a beacon of inspiration for liberation processes and indigenous movements, from the comuneros in New Granada and Chile to the struggles of the nineteenth century. San Martin’s independence movement would uphold the emancipation promise toward slaves, and in the twentieth century, his figure would be a symbol of social struggle and indigenous dignity.

Throughout history, an image and a message Tupac Amaru II It has been reinterpreted through national projects and social movements. The government of Juan Velasco Alvarado (1968-1975) saved him as a founding authority, and his face was stamped on public squares, stamps and monuments. It also inspired political movements such as the MRTA in Peru and the Tupamaros in Uruguay.

In popular culture, his name crossed borders: American rapper Tupac Shakur It was named in his honor, and numerous groups in Latin America claim his legacy. On a symbolic level, it is linked to the myth of Incari, the Andean hope for restoration and redemption.

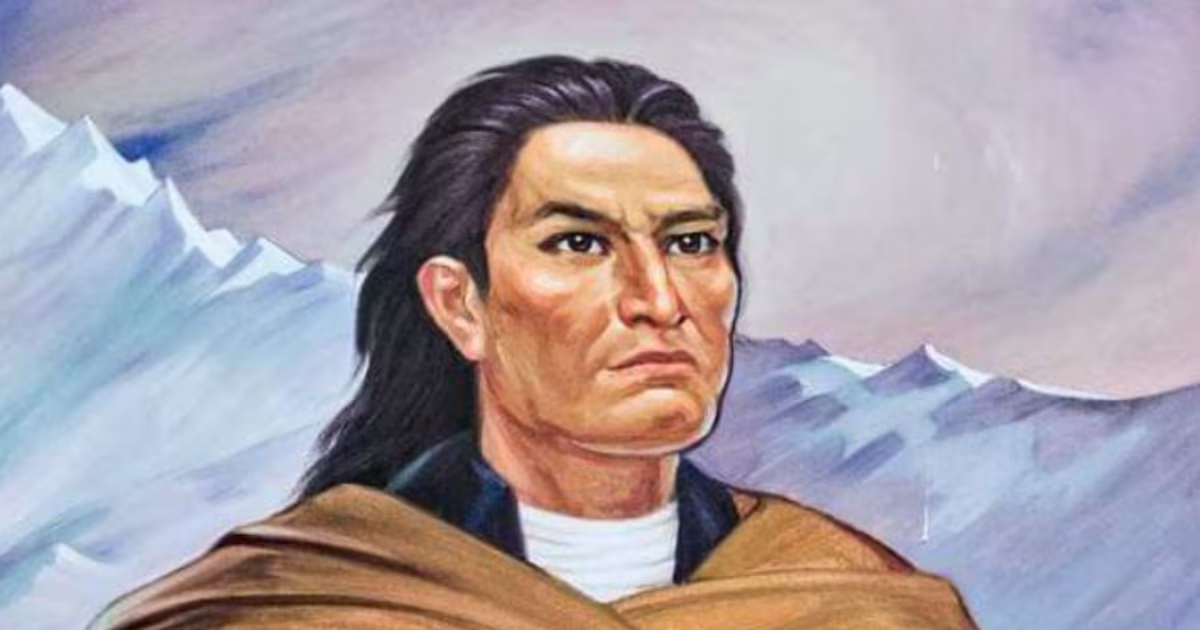

Although there is no documented contemporary portrait, accounts from the time describe him as a man of noble character, tall stature, aquiline nose, and a firm voice. He was polyglot, fluent in Spanish and Quechua, and had a rare and advanced multicultural education in the colonial era.

Today, Túpac Amaru II continues to lead marches, songs, artwork and debates across the continent. It is a symbol of resistance against oppression, a symbol of indigenous dignity and the unfinished promise of social justice in Latin America.

The name José Gabriel Condorcanqui lives in history as synonymous with courage, rebellion and hope. His life and sacrifices continue to remind us that the voice of the people, in the face of injustice, cannot be silenced.