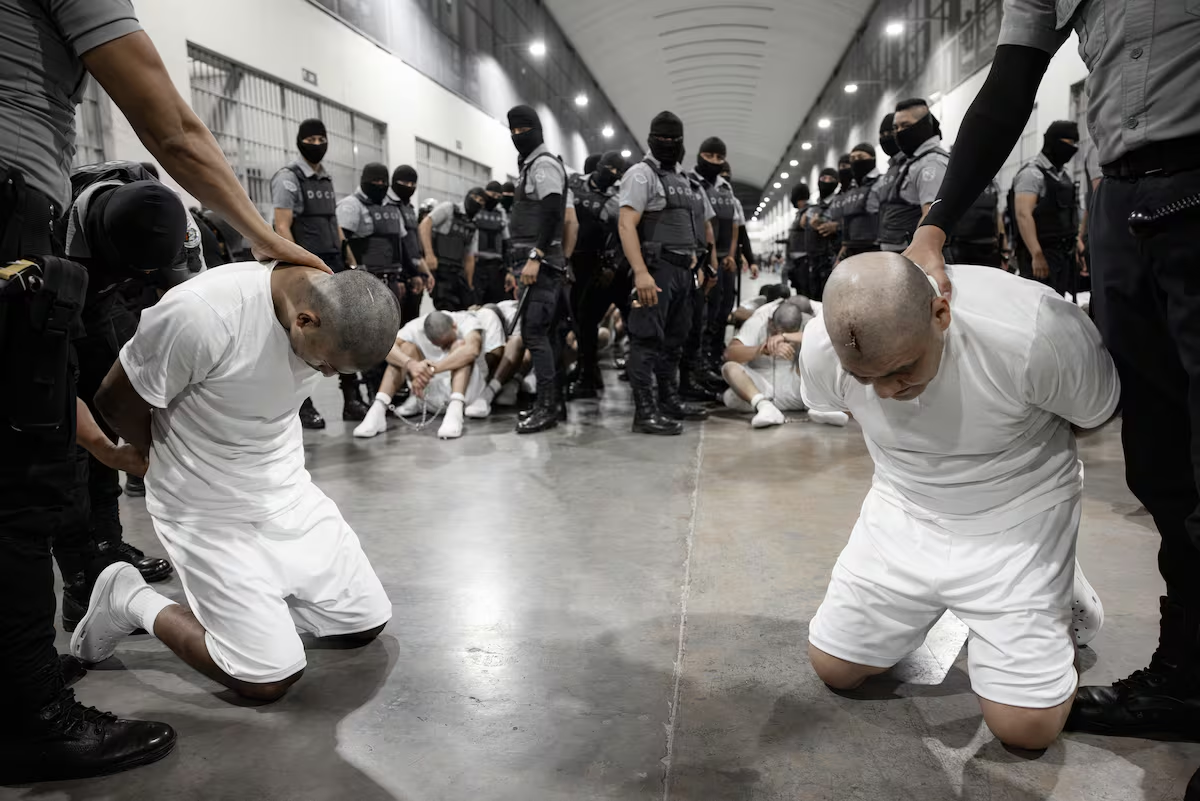

Pictures of Lewis’ teeth without one of his front pieces and Daniel’s nose with a clearly deviated septum are part of the evidence collected in the report They have come to hellfrom Human Rights Watch, which was published on Wednesday. The document reveals torture and other abuses against Venezuelans in El Salvador’s Terrorist Detention Center (Sicot), the massive Nayib Bukele prison. There are also photos of the round scars on Mateo’s hand and on Carlos’ chest, who were shot at close range by rubber bullets while being held in the cells of this prison.

The consequences are still evident almost four months after 252 Venezuelan migrants endured the worst part of the nightmare. US immigration police detained them at different times, in different cities and in different situations – raids on their homes, when crossing the border – and on March 15 of this year, President Donald Trump decided to send them to prison in El Salvador, citing the Alien Enemy Act and accusing them of being members of the Aragua train gang. They experienced horror: daily portions of beatings. After reaching an intergovernmental agreement, mediated by the church, they ended up on July 18 being sent to Venezuela, a country some of them had long since left, in some cases fleeing political persecution. In exchange for the Venezuelans, Nicolas Maduro’s government handed over 10 American prisoners to Washington.

Human Rights Watch, relying on the NGO Cristosal, research centers, official documents, and forensic specialists, reconstructed the torture system in Sicot based on the testimonies of Venezuelans who stayed four months and three days in a place built so that almost no one could leave. The report protects the identities of the 40 victims directly interviewed and dozens of family members, friends and lawyers who spoke with them to build the cases of 130 of the 252 Venezuelans the Trump administration sent to a Central American prison. Their names have been changed for fear of retaliation and because many of them have taken legal action against the governments of the United States and El Salvador.

Daniel suffered a broken nose after participating in interviews conducted by International Red Cross staff with a group of Venezuelan prisoners on 7 May. They beat him with a stick and punched him in the nose, causing him to bleed severely. The report stated: “They continued to hit me in the stomach, and when I tried to breathe, I started choking on blood. My nose was deviated from those blows.”

And he wasn’t the only one. “After the interview, they came in the afternoon to take us out of the cell to a search site and beat us again and told us it was because they told the Red Cross about the beating,” Flavio said. “They only beat me that afternoon, but they beat other classmates throughout the next week.” But psychological torture was what affected him the most, this detainee says. “The hardest thing is that the guards told us that we would never get out of there, and that our families abandoned us to die.” The phrase they repeated most often was that “the only way out of here (Sikot) is in a black bag”; That is, dead. The 252 Venezuelans can say that.

The hardest hits

On the eve of visits, such as the three visits by the Red Cross in May and June, or the visit by Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem in March, they were provided with blankets, pillows and personal hygiene products to improve their conditions. After the guests left, their belongings were taken from them and the beating intensified. Two or three days before they were finally sent to Venezuela, they also improved the treatment, but they also gave them a final beating.

As soon as they got off the plane, they started beating them. “One of the officers hit me in the face, right in the mouth, with a black baton, and broke one of my front teeth,” Lewis says. Other officers also punched him in the ribs and hit him on his right knee with a stick. He said, according to the report: “The doctor who examined me told me later, after about a week in prison, that they had torn ligaments in my knee. They did not give me anything for my tooth.”

The investigation documented sexual violence. One detainee said that four guards sexually assaulted him when they took him to a solitary confinement cell called “the island,” where they regularly punished those they considered to be violating the rules with further beatings, solitary confinement, and deprivation of food and water. “They played with their sticks on my body,” Mario said. “They put sticks inside my legs and rubbed them on my genitals.” They then forced him to perform oral sex on one of the guards, groping him and calling him a “faggot.” Another detainee, Nicholas, said that he was sexually assaulted during the beating. The officers grabbed his genitals and made comments of a sexual nature. “They did this to a number of people,” he added. “I don’t think other people will tell you because it’s very intimate and embarrassing.”

Human Rights Watch notes that “beatings and other abuses appear to be part of a practice aimed at subjugating, humiliating, and disciplining detainees by inflicting severe physical and psychological suffering.” Investigators warn that according to testimonies, the security guards wore gray and black uniforms, their faces were always covered, and they called each other nicknames such as Devil, Tiger, Crow, Vegeta also tiger and They had full authority to treat the prisoners as they did. “The brutality and repeated nature of the abuse also seemed to indicate that the guards and riot police acted in the belief that their superiors supported, or at least tolerated, their abusive actions,” the report said.

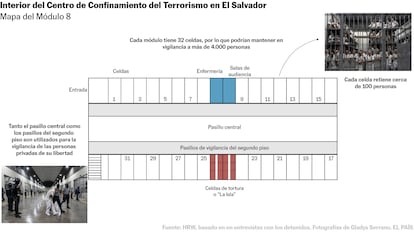

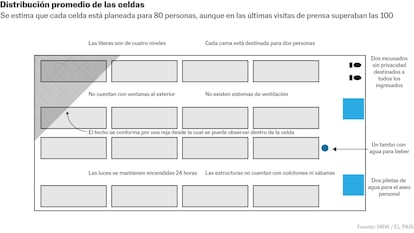

Forgetting in three countries

According to Human Rights Watch, Sikut does not comply with many standards of international human rights law and the so-called Mandela Rules that ensure prisoners are treated with dignity. Inaugurated by Captain Bukele in January 2023, under the emergency regime, it has become a torture machine that forms part of the institutional apparatus of the Salvadoran president. There is a history of serious human rights violations committed in this prison. The organization condemns, saying: “The United States sent the 252 Venezuelans to Sicote despite credible reports indicating that torture and other abuses were being committed in El Salvador’s prisons. This violates the principle of non-refoulement, stipulated in the Convention against Torture, among other conventions.”

Almost everything in this process is irregular. The governments of the United States and El Salvador have refused to disclose information about the whereabouts of the 252 people, or what their fate is, to the point that their actions – or inaction – constitute the crime of enforced disappearance under international law, the report denounced. This crime occurs when the government detains a person and refuses to provide information about their whereabouts or what will happen to them, leaving them without legal protection and causing additional hardship for families. Human Rights Watch also condemns the detention of Venezuelan migrants in Sicot as having no legal basis, making it arbitrary under international humanitarian law.

Once they were arrested in Sicot, the Venezuelans were unable to contact their families or lawyers. Neither San Salvador nor Washington ever published an official list of the names of those affected, nor did they confirm the unofficial list that had been circulated. US immigration authorities assured the group members that they would return them to Venezuela. None of those interviewed were informed that their real destination was El Salvador.

For families, a certain version of hell has begun, without knowing the whereabouts of their loved ones, and with bureaucracy turning into an instrument of psychological torture. The names disappeared from the computer system along with the detainees’ location, shortly after the transfer and, apparently, “before ICE’s usual schedule.” American lawyers denounce for each other that the immigration authorities never informed them of the transfer of their clients.

Families found themselves trapped in a system where, when they were able to speak to someone to request information at ICE offices or detention centers, officials’ responses were infuriating: Either their loved one’s name did not appear in the system, their whereabouts were unknown, or they were unable to provide them with information. In the best case scenario, it was confirmed that their relative would be deported, although the location of their deportation was not revealed to them. For some, the only proposed solution was to contact the “Venezuelan Embassy in the United States,” even though it has been closed for years.

Attempts to contact the Salvadoran Presidential Commissioner for Human Rights, Andrés Guzmán Caballero, via email, only received an automated message in response: his request had been transferred to the “competent institutions.” And then there was administrative silence.

Human Rights Watch highlights that Salvadoran courts have also refused to provide information about the whereabouts of the Venezuelans. Between March and July, Cristosal helped file 76 petitions Habeas corpus order Before the Supreme Court without obtaining a response. At the end of March, the General Directorate of Punitive Centers of El Salvador responded to this organization that the list of people affected by this measure had been declared confidential for seven years, and for this reason they could not report their names. El Salvador assured the UN Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances that it did not detain the Venezuelans, but rather “facilitated the use of Salvadoran prison infrastructure to detain persons detained within the jurisdiction and law enforcement system of that other State,” meaning the United States.

With their release, only part of the nightmare has passed for these men. “I am on alert all the time because every time I hear the sound of keys and handcuffs, it means they are really coming to hit us,” Daniel told Human Rights Watch. The detainees confirmed that they were psychologically affected by what they were exposed to. In Venezuela, they underwent medical examinations, interviews in state media, and background checks before being sent home. They did not receive psychological support to deal with the trauma that followed. The report indicates that two of the detainees stated that agents of the Bolivarian National Intelligence Service (SEBIN) went to their homes after their return. A number of interviewees said: “I live in fear.” According to the report, the agents said the visits were “part of the surveillance process.” They asked them to record videos of their detention in the United States, the treatment they received, and asked them, among other things, whether they had contacts with US agencies seeking to “destabilize the government.”