When Seymour Hersh revealed the massacre committed in 1968 by American soldiers at My Lai against Vietnamese civilians, including babies, the journalist was accused of violating the national interest. It was difficult to publish the report. The horrors earned him many sleepless nights and a Pulitzer. In 2004, he denounced the torture and abuse suffered by prisoners at Abu Ghraib after the US invasion of Iraq. The Armed Forces sizzled again. From his peers, he received the epithet “he who shakes power”. Stubbornly active at 88, he is at the origin of “Seymour Hersh: In Search of the Truth”, a documentary by Laura Poitras and Mark Obenhaus, pre-nominated for the Oscars and available from Friday on Netflix.

- $42 million: Company subcontracted by the US military found guilty of torturing Iraqis in Abu Ghraib prison

- “We cannot let history repeat itself”: Bernie Sanders compares attacks on Iran to invasion of Iraq

It’s been two decades since Poitras, after devouring Hersh’s New Yorker texts on the George W. Bush administration’s war on terrorism, wanted to co-opt him for the film. Profiling him, he argued, would be ideal for exposing the cycle of abuse of power in Washington since the 1960s. The journalist then justified his refusal by the need to protect his sources.

Three years ago, the death of informants, the insistence of Poitras and the films she made at that time ensured her approval for the project. “In Search of the Truth” ended with Donald Trump returning to the White House, as reflections on the precarious state of American democracy, the spread of fake news and Washington’s siege on a press in crisis are on the agenda.

— Today, the consequences of impunity for crimes committed by those in power are clearer. Unfortunately, the scale of what I wanted to show increased. On the other hand, the positioning of the film has strengthened — the director told GLOBO, via video call.

/i.s3.glbimg.com/v1/AUTH_da025474c0c44edd99332dddb09cabe8/internal_photos/bs/2025/U/R/vYI2bfSlmkJRZUMwxt0A/cover-up-00-31-01-07.png)

When he contacted Hersh in 2005, Poitras, then 41, had just made his first feature film, “My Country, My Country,” set in occupied Iraq. A decade later, he would receive an Oscar for “Citizen Four,” based on Edward Snowden’s revelations about the secret surveillance programs of the U.S. National Security Agency. Then he looked at WikiLeaks and Julian Assange for his “risk”. And last year he received the Golden Lion in Venice for “All Beauty and Carnage,” about the political activism of American photographer Nan Goldin.

Hersh has seen the films. And he took note of the risks associated with the work of one of the founders of the Intercept platform, which he would later leave.

— Sy’s work (as his friends call him) is so impressive that I don’t consider putting myself on his level. I identify parallels, in the interest in unofficial narratives, in questioning the limits of power. And I know that mutual respect contributed to him finally saying ‘yes’ to me,” Poitras said.

“In Search of the Truth” follows Hersh’s trajectory to reinforce the importance of detecting and combating the cancer of impunity for the health of democracies. At GLOBO, Poitras compared how the institutions of the two largest democracies in the Americas have dealt with the disease. He called the trial and conviction of former President Jair Bolsonaro, who so far “bears the consequences of his actions” a “good sign”:

— This has never happened in the United States, and not just with Trump. (Vice President) Dick Cheney normalized torture and did not die in prison. (President) Richard Nixon resigned and was pardoned. On the other hand, the killing of more than a hundred people during the police operation in Rio last month demonstrates that cover-ups further fuel the cycle of impunity in this country.

/i.s3.glbimg.com/v1/AUTH_da025474c0c44edd99332dddb09cabe8/internal_photos/bs/2025/L/A/uiwL0eQ9Oyv2RtjQTdzg/112917823-files-this-june-2-2008-file-photograph-shows-then-us-vice-president-dick-cheney-listening.jpg)

In the United States, many critics, in praising “In Search of Truth”, questioned whether Hersh’s achievements would be possible today, in a fragmented media landscape and with an uninterrupted news cycle. Poitras believes that documentarians fill the gaps left by professional journalism.

— I highlight the work of Petra Costa, who, with “Democracy in Vertigo” and “Apocalypse in the Tropics” (also pre-nominated for an Oscar), treats the theme in a masterful way, based on Brazilian reality. She’s brilliant — he told GLOBO.

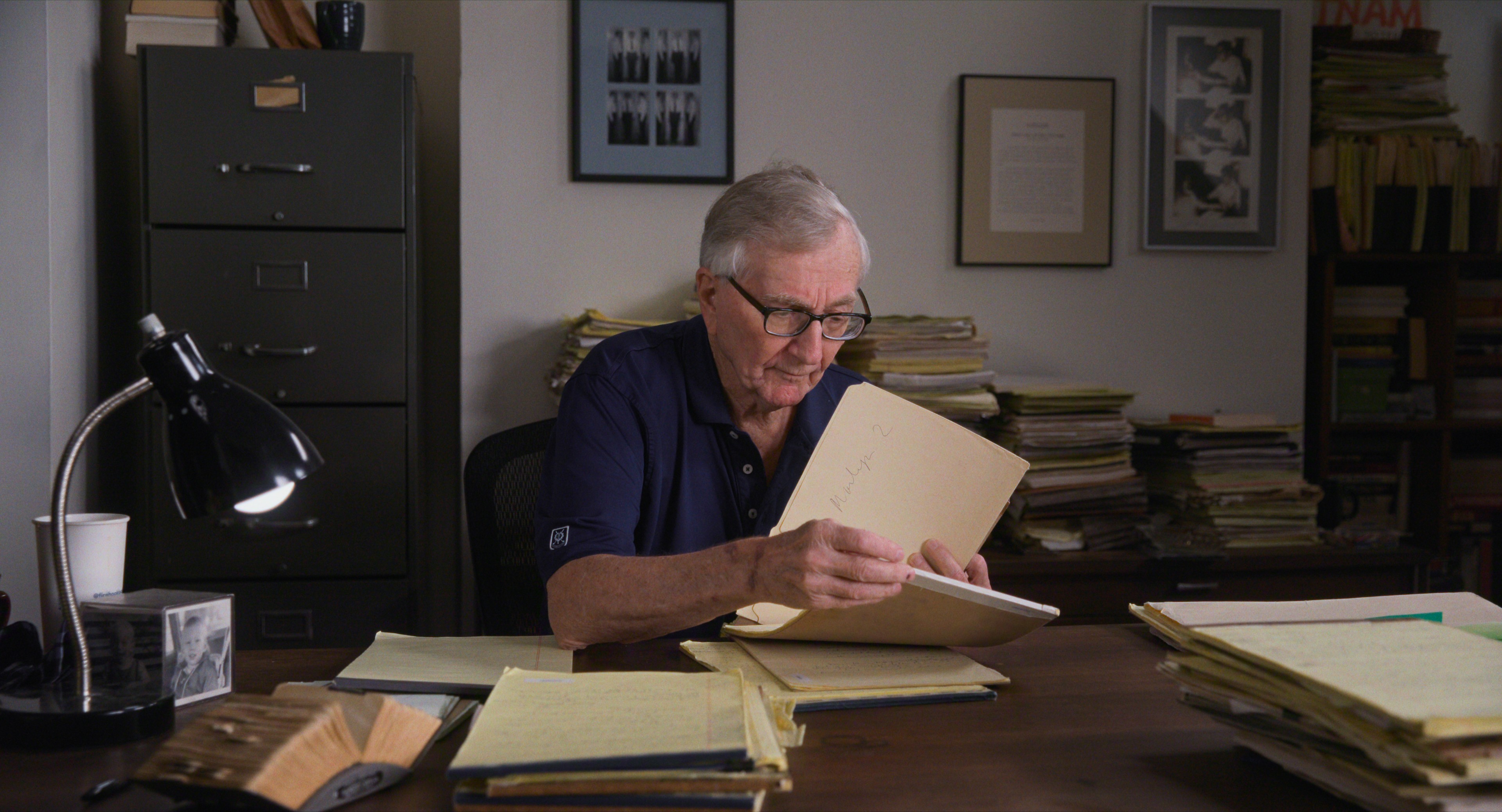

One of the strengths of “In Search of the Truth” is the surgical use of archive images. Hersh offered, for the first time, and with great reluctance, unrestricted access to his heavy and chaotic trunk, from his notes from the late 1960s to his conversations with sources in Gaza over the past two years. Images, drafts, documents and audio from Vietnam, the fall of Nixon, the coup in Chile and the CIA investigations illustrate the enormity of the work.

/i.s3.glbimg.com/v1/AUTH_da025474c0c44edd99332dddb09cabe8/internal_photos/bs/2024/f/0/WBmBRATP2ATuxr1JB0jw/800px-abughraibabuse-standing-on.jpg)

Hersh recounts in the film how leaving his phone number during a radio interview led him to the source that provided him with the Abu Ghraib footage. How the woman found the photos is another gem of the documentary. The film also presents new information about the reporter’s departure from the New York Times in 1979, as he investigated growing corporate power and allegedly clashed with the interests of not only the paper’s owners, but also those in charge of journalism. After appearing in the New Yorker and collaborating with the London Review of Books, he now publishes on Substack, on the “It’s Worse Than You Think” page, with over 200,000 subscribers.

/i.s3.glbimg.com/v1/AUTH_da025474c0c44edd99332dddb09cabe8/internal_photos/bs/2025/R/k/3H7O3CRqAlY6Syncnr8g/35038085-a-handout-picture-released-by-the-syrian-arab-news-agency-sana-shows-syrian-president-basha.jpg)

One of the documentary’s most delightful moments takes place in the reproduction of Nixon’s conversation with his secretary of state, Henry Kissinger, when they referred to Hersh as “that son of a bitch who’s always right.” But the film proves that this wasn’t always the case. The reporter was also wrong. In one of the most famous errors, Hersh admits to having questioned the accusation made by opponents of Bashar al-Assad’s regime that he had ordered, as it later turned out, the use of poison gas against the population. His source, with whom he spoke often, was the dictator himself.

— At first, Sy was hesitant to broach the subject. But then he understood that we were just looking for something that he particularly cares about, which is precision,” said co-director Mark Obenhaus.