For decades, the mosasaurs have been described as large marine predators from the late Cretaceousreptiles perfectly adapted to the ocean and linked to ecosystems coastal and high seas. A new study published in Zoology BMC partially challenges this image by documenting find a tooth of mosasaur in a river environment fresh waterwithout evidence of direct marine influence, in present-day North Dakota, United States. This discovery provides new clues about the possible ecological flexibility of these animals in the last moments before their extinction.

Where did they find the part?

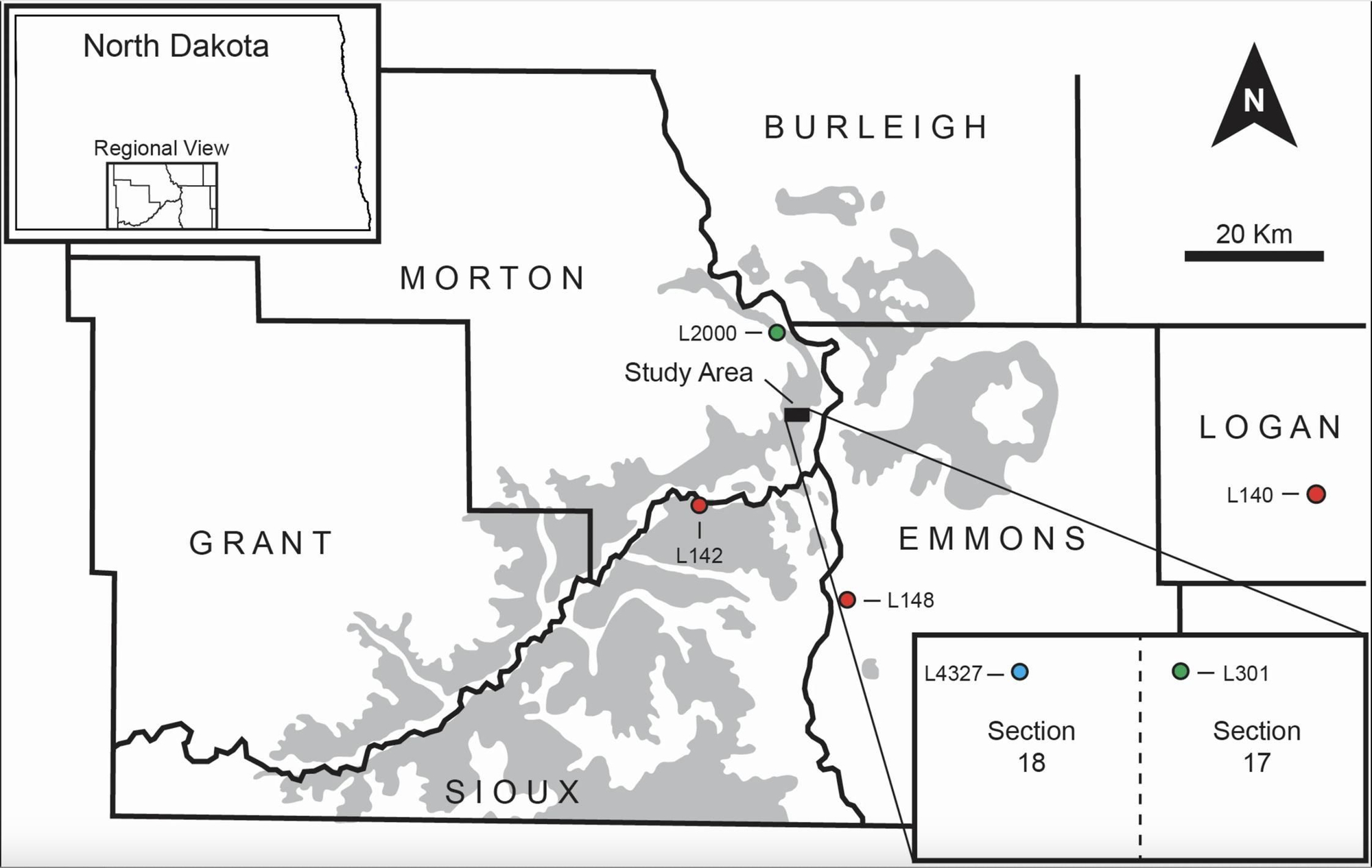

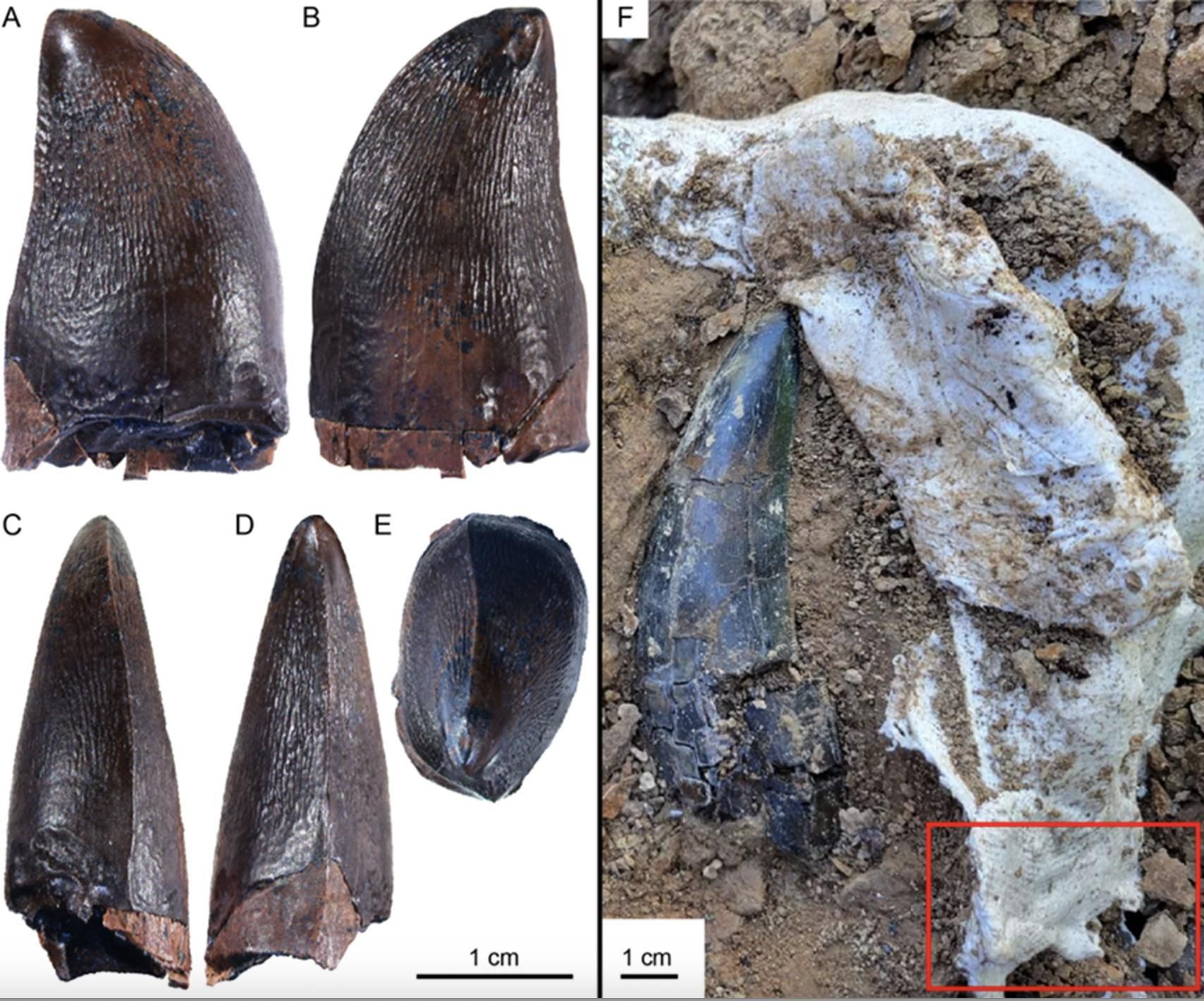

The fossil, a dental crown the isolate identified as NDGS 12217 was recovered in the Hell Creek Formationa site famous for its abundance of remains of dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus rex or Edmontosaurus, but practically devoid of marine fauna. The tooth appeared to be embedded in a layer of carbonaceous clays interpreted as a floodplain associated with a fluvial system, with no taphonomic indication of transport from coastal or marine environments.

He around where the fossil was located is dominated by the remains of terrestrial and freshwater animalsnotably crocodiles, herbivorous dinosaurs and large theropods. The absence of ammonites, sharks or other marine organisms reinforces the interpretation of a strictly continental context. Furthermore, the good state of conservation of the toothwithout abrasion or fractures attributable to transport, suggests that It was lost on site by the animal itself and not extracted from another medium.

According to the morphological analysis

From a morphological point of view, the tooth presents a finely wrinkled texture and well-defined carinae, characteristic traits of the tribe Prognathodontinia group that includes some of the mosasaur species of bigger size known. Although the material is insufficient for precise assignment to the species level, the authors point out that the specimen could match to an animal up to approximately 11 meters longa size inconsistent with the patterns observed in juvenile individuals.

The main contribution of the study lies in the geochemical analysis of dental enamel. The team analyzed the “chemical fingerprint” of tooth enamel to compare it to other fossils from the same environment and to those from Cretaceous seas. The results show that the isotopic signal of the tooth does not match that of late Cretaceous marine environmentscharacterized by a very homogeneous composition, but aligns consistently with that of terrestrial and freshwater animals from the same site.

This is not a unique case: there are already other precedents

The presence of mosasaurs in non-marine environments It’s not completely new. In Europe and Africa they have been described smaller species with adaptations to estuarine or river systemsas Pannoniasaurus in Hungary or Goronyosaurus in Niger. However, these cases corresponded to medium sized animals and with specific anatomical features, while the Hell Creek finds indicate large mosasaurs traditionally considered strictly marine.

The study is also located in a environmental context of profound transformation: the gradual decline of the Western Inland Sea, which divided North America for millions of years. In its final stages, this sea experienced gradual desalination and the expansion of large river systems, a scenario in which some mosasaurs were able to temporarily adapt to less salty, or even fresh, waters in response to a changing environment.

Far from completely rewriting the history of these reptiles, Discovery qualifies classic picture of mosasaurs as exclusively oceanic predators. Rather than rigid specialists, some lineages appear to have demonstrated a notable capacity for ecological adaptation in the later stages of the Cretaceous. A single tooth doesn’t change the ending of its story, but it does expand the framework in which it developed: a more dynamic world with less defined ecological boundaries than previously thought.