These cold and rainy days allow you to admire the views while strolling along the Plaza de España and Paseo de Bailén. Protected by construction networks, a constant, temporary coming and going of vehicles and a backup of metal ditches, it waits for the moment to regain its essence, which is perhaps the last architectural jewel of one of the most recognizable neighborhoods of Madrid.

Behind this sentence full of subordinate clauses, it evokes the rehabilitation of the building which housed the former headquarters of the Real Compañía Asturiana de Minas. The last Alphonse museum – in reference to Alphonse XII – which will build the capital. Now, the plans were drawn up in 1895. Declared Asset of Cultural Interest (BIC) in 1977, it is the property of Mutua Madrileña. The insurer has invested around $30 million to create a new cultural center in Madrid, which will also serve as the headquarters of its foundation, thanks to a laborious restoration process that began in 2024 and is expected to be completed during the summer of 2026.

The mapping is precise and recognizable. Find your life at number 8 Plaza de España. The sea, next to the Senado and in front of the Sabatini gardens. When it is completed and begins its activity, it will bring a new cultural eje to Madrid de los Austrias, with the Royal Palace and the Gallery of the Royal Collections.

Some 300 people participated in the rehabilitation work on the building, coordinated by the construction company Fernández Molina, according to the project by architect Fernando Espinosa de los Monteros. It covers more than 4,000 square meters and is intended to be a center for the dissemination of culture, arts and human sciences run by Fundación Mutua.

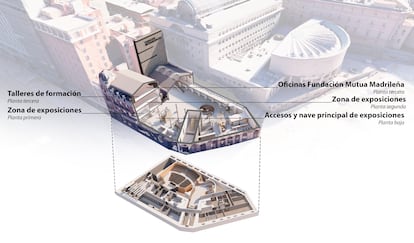

After completing its rehabilitation, it will have exhibition halls distributed among three factories, classrooms and rooms for cultural and social activities, as well as an auditorium with a capacity of approximately 210 people. The plantation is a crossroads that connects different generations. A piece that, envisaged from the beginning, reveals a “V” shape and creates a bisagra between the streets Bailén and the Plaza de España. Waiting inside, according to his responsibilities, including Eiffel.

Construction of the building, intended to house the Madrid headquarters of the Spanish-Belgian company Asturiana de Minas, began in 1898 in a city that was still trying to define itself as a modern capital. The tension between classicism and modernity coexists. A tension that crosses many corners of Europe. If Paris was the laboratory of major urban experiments and Berlin was developing with industrial power, Madrid seemed to be debating between a monumental Castellane villa or an urban center capable of dialogue, on an equal footing, with the European capitals.

The future building of the Fundación Mutua Madrileña is the mirror of this research. For example, laid tiles, Berroqueño granite from the Sierra del Guadarrama and, of course, zinc. “I’ve been in this business for four decades and I’ve never seen a building like this,” admits Espinosa de los Monteros. And then, with this emotion of coming, for the first time, to an unexpected place: “There are few things as enriching as working in a historic building and giving it a new use. Because it means, at the same time, restoring this part of the heritage and providing solutions of the times. We also recover a letter included in the acronyms BIC, its commitment to culture, subraya.

The basic project combines a small palace building — mainly for its three-towered top — with an industrial building at the rear, which was intended, at the same time, to be the central workshops of the mining company and to serve as a warehouse for the distribution of the zinc-derived products that the company manufactured.

This is the beginning of the beginning. The facades are an authentic repertoire of ornamental elements made of silicate-painted zinc. Balustrades, railings, cornices, finishes, crowns and covers. Vendían, let us think, to hotels like the Ritz. The visitor, from the moment he leaves, understands the eclectic sense of the original building. The ladrillo takes up the Mudejar tradition and the masks, lion heads, geometric and plant elements brought to Renaissance classicism. There will be tools or screws, machine supplies scattered and scattered, which keep the industrial character of the business alive.

The structure of use – in the language of architects – is clear. The plan of the lower floor and the old nave of the warehouse (18 meters high) will be the first area that will house exhibitions, to which will also be added, with the same purpose, the first and second, while the third will host courses, workshops and workshops at the Fundación Mutua Madrileña. “We have a large space to offer those who visit us a range of high-quality, attractive and innovative exhibitions, both in culture and art and in the treatment of social themes,” describes Lorenzo Cooklin, general director of the Fundación Mutua Madrileña.

And Eiffel? Where is the maestro? The architects are convinced that a ruined wrought iron staircase, currently being restored and which causes emergency exits, comes from its height. Thanks to his design and Eiffel’s participation in other projects in Spain at that time, Martínez Ángel probably counted on the inspiration of the French genius for another novelty. An above-ground iron wall that runs through the upper part of the warehouse and adapts to the climate. Imagine a strong wind. Even on a millimeter scale, you can see the bamboo yielding and correcting itself with air. The secret lies in hinges that transform it into a hinged structure. Meanwhile, a beautiful lamp rests its days in a room cared for by experts.

The building is the last of its kind because it belongs to a disappearing world: historicist eclecticism, industrial optimism and large mining companies. The radical changes of modernism, rationalism, the architecture of hierarchy and the armed hormigón in its purest version were very quickly achieved. But the future building of the Fundación Mutua Madrileña and which is today being renovated, often in an artisanal way, remains as a testimony: the memory of a time when Madrid wanted to look at Europe and it remains with an architecture which was, at the same time, this memory and this promise.