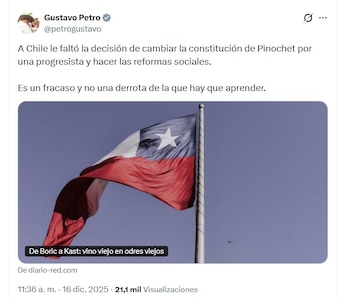

Through a message he shared on his on the morning of Tuesday, December 16, 2025

The head of state left a short but powerful message that, according to his vision, helped Kast’s (right-wing) political project prevail over Jeannette Jara (left-wing).

You can now continue following us Facebook and in ours WhatsApp channel

Petro went even further and risked questioning without naming names, but in his opinion more could have been done to prevent the return of the right to power in the southern country led by Gabriel Boric.

“In Chile there was no decision to change (August) Pinochet’s constitution in favor of a progressive one and to carry out social reforms. “It is a failure and not a defeat from which we must learn,” was the conclusion drawn by the Colombian president in his message, calling on governments with a similar current to Petro to reflect.

The message was accompanied by an article published by the portal Network diary from Chile.

In addition to his words, the Colombian president included an opinion column entitled From Boric to Kast: old wine in old wineskinsand written by Lautaro Rivara for Network diaryin which he examines the root causes of the advance of the far right in Chile following the presidential victory of José Antonio Kast and the factors that led to the subsequent failure of the progressive cycle led by Gabriel Boric.

Rivara is developing Several hypotheses to explain how a society that was the protagonist of the social outbreak of 2019 ended up choosing a personality associated with the legacy of Augusto Pinochet.

As a starting point, journalist Rodolfo Walsh cites: “The masses are not retreating into the void, but into bad but familiar territory” and analyzes how the re-establishment impulse of the 2019 protests led to the beginning of a constitutive process driven by the demands of the sectors left behind by the neoliberal model.

Rivara recalls that this mobilization cycle brought together the demands of students, indigenous peoples and workers affected by widespread privatization and social inequality. In the author’s words: “In Chile, the holy trinity of the authoritarian general, the neoliberal economist and the secret service agent became a school.”

The analysis asserts that “the Chilean tragedy is the result of the fatal divorce between a highly institutionalist state left… and a more dispersed, anti-state social left, which even exhibits strong autonomous and anarchist tendencies.”

Rivara believes that while the social left failed to articulate an inclusive state project, the institutional left linked to the urban and Santiago elites stayed away from the spirit of the outbreak.

Aside from that, The author cites Boric’s role during the government of Sebastián Piñera as a turning pointwhen, as the author states, the then-MP “facilitated a monitored voter transition and closed the Pandora’s box that had been opened in October.”

Rivara argues that the constitutional process led to defeat when, first, the proposal for a new constitution was rejected by 61% of voters and then the project prepared by the right also failed, ensuring the continuity of the 1980 constitution.

Given this panorama The column raises a central question: Was what happened in Chile a defeat or a failure for the left? Rivara responds that “we are faced with a new failure of an institutionalist and elitist left, more liberal than progressive,” and attributes the setback to internal contradictions, a lack of leadership and the absence of forceful responses to societal demands.

Examining the government of Gabriel Boric, the author points out that “Chilean liberal-progressivism has failed” and that even the achievements shown – such as the reduction in weekly working hours and pension reform – were limited or not fully implemented.

For Rivara “Inequality was hardly reduced compared to the presidency of a staunch neoliberal like his predecessor Piñera. Precarious and unregistered employment remained at very high levels. Collective bargaining and centralized bargaining were never implemented.”

In a more regional and global context, the article warns of the rise of a heterogeneous right made up of “red-blooded Pinochetists, paleolibertarians, evangelical and Catholic traditionalists, conservatives of all stripes” who knew how to channel social discontent.

“The opportunity has been fatally missed, and the country that was a promising exception six years ago is now the expression of one of the most reactionary crystallizations of global trends in progress.”diagnoses the journalist.

Rivara emphasizes that the electoral success of Kast and other right-wing candidates is partly due to the left’s loss of relations with workers and its inability to offer concrete solutions to the problems of the economy and security, minimum demands that are, in his words, “the glue in this situation.”

The columnist affirms that “where the left does not have the courage to face the real enemies (nor the pedagogical ability to explain them), the false enemies are sacrificed in their place: be they communists, Mapuches, feminists or migrants.”

Finally, Rivara argues that the current Chilean left “feared its people more than the legacy of the tyrant and his contemporary reincarnations,” and warns that progressivism “reopens the floodgates to reaction,” as has happened in other countries in the region.

Finally, the author recalls the slogan of the “No” campaign (the same title of a 2012 film by the Mexican Gael Bernal) against Pinochet and ironizes: “It will take a little longer for joy to arrive. But it will.”