Guan Heng found himself stuck in the dust, risking everything to shoot on location in China’s northwestern Xinjiang region. After his videos were uploaded online, they showed the world where Chinese authorities were detaining Uighurs and other ethnic minorities.. In 2021, the first Trump administration declared China’s campaign in Xinjiang a form of genocide. A few months later, Mr. Guan fled China and crossed the U.S. border to seek asylum. But that made him a target of the second Trump administration, which arrested Mr. Guan in August for crossing the border illegally.

On December 15, a U.S. Department of Homeland Security lawyer said Mr. Guan could be transferred to Uganda to seek asylum. However, his lawyer Chen Chuangchuang believes Uganda would likely send him back to China. This would happen despite the principle of non-refoulement, which prohibits states from sending people back to a country where they may suffer abuse, he adds.

An estimated one million Uighurs and other ethnic minorities were detained in “re-education” camps during China’s security crackdown between 2017 and 2019.. Some of the camps were closed; others were converted into factories or prisons, and the people living in them were released, sent to hard labor, or imprisoned. Uighurs who went abroad were separated from their families; Many sought asylum in countries such as Canada, where governments accelerated resettlement processes.

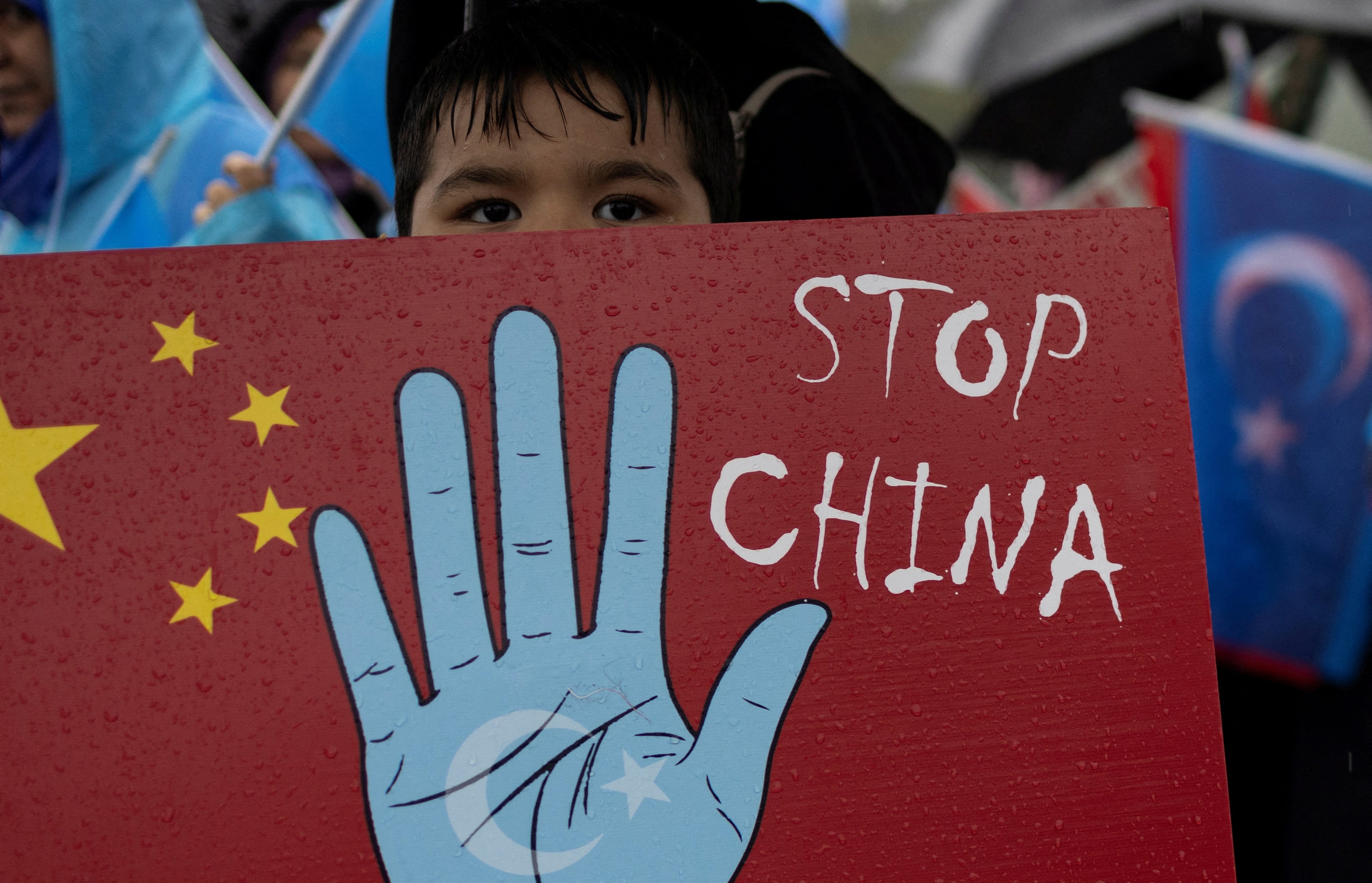

Now the Uighur refugees are losing their protection as China pressures other countries to extradite them and the United States and Europe become increasingly hostile toward the refugees. China is promoting Xinjiang as a tourist haven and a safe place where Uyghurs should return. Authorities deny that human rights violations have occurred in the province. These accusations are the “lie of the century,” says Lin Jian, spokesman for the Foreign Ministry. “Xinjiang enjoys economic growth, social stability and harmony among all ethnic groups, and its people live better lives.”

In February, Thailand deported 40 Uyghurs who had been imprisoned in Bangkok for a decade to China despite UN protests. Turkey, a former hub for exiled Uyghurs based on their shared Turkish roots, has revoked the residence permits of some Uyghurs, detained them in deportation centers and pressured them to sign “voluntary return” forms, according to Human Rights Watch (HRW), a monitor of such matters. Since 2024, Turkish courts have ruled that non-refoulement does not apply to Uyghurs because they cannot be threatened with ill-treatment or torture in China. And last month, Germany deported a Uighur woman to China after her asylum application was rejected. German authorities said it was a mistake and the woman managed to quickly leave China for Turkey, but the incident raised greater fears, says Louisa Greve of the Uyghur Human Rights Project, a charity in Washington, DC

Meanwhile, China is allowing some Uyghurs to travel in and out of Xinjiang to assert its claim to normality. In recent months, official media have shown returning Uighurs on state-sponsored trips to Hotan, Kashgar, Urumqi and Turpan, often waving Chinese flags, taking photos with “Thank the Party” banners and expressing pride in Xinjiang’s development under Chinese leadership. The Uyghurs who take part in these trips “know everything is wrong” but they cooperate so they can see their families, claims Yalkun Uluyol, an HRW researcher who interviewed 23 Uyghurs traveling in and out of China.

Chinese authorities portray the repatriation targets as criminals who broke the law by crossing the country’s borders and as potential terrorists who could attack China. They are particularly concerned about the Uyghurs in Syria, who have combat experience and speak threateningly of revenge against China. The Syrian government has vowed not to allow Syrian territory to be used for “activities that undermine China’s national security, sovereignty and interests.” In November, rumors emerged that Syria was planning to deport 400 Uyghurs to China after the country’s foreign minister’s official visit to Beijing, but Syrian authorities denied this.

Syria is in a delicate situation. Thousands of Uighur fighters have joined the country’s new army. A Uyghur commander named Abdulaziz Dawood Khudaberdi, also known as Zahid, was also reportedly appointed brigadier general. The largest Uyghur militant group, formerly known as the Turkestan Islamic Party, has also changed its name. Now it looks like this a community organization that supports Uighur language schoolsexplains Abduweli Ayup, a researcher who visited northwestern Syria in October. But he also met more radical Uyghurs who still want to “Fight China as quickly as possible”. As long as this threat exists, China’s global hunt for Uyghurs will continue.

© 2025, The Economist Newspaper Limited. All rights reserved.