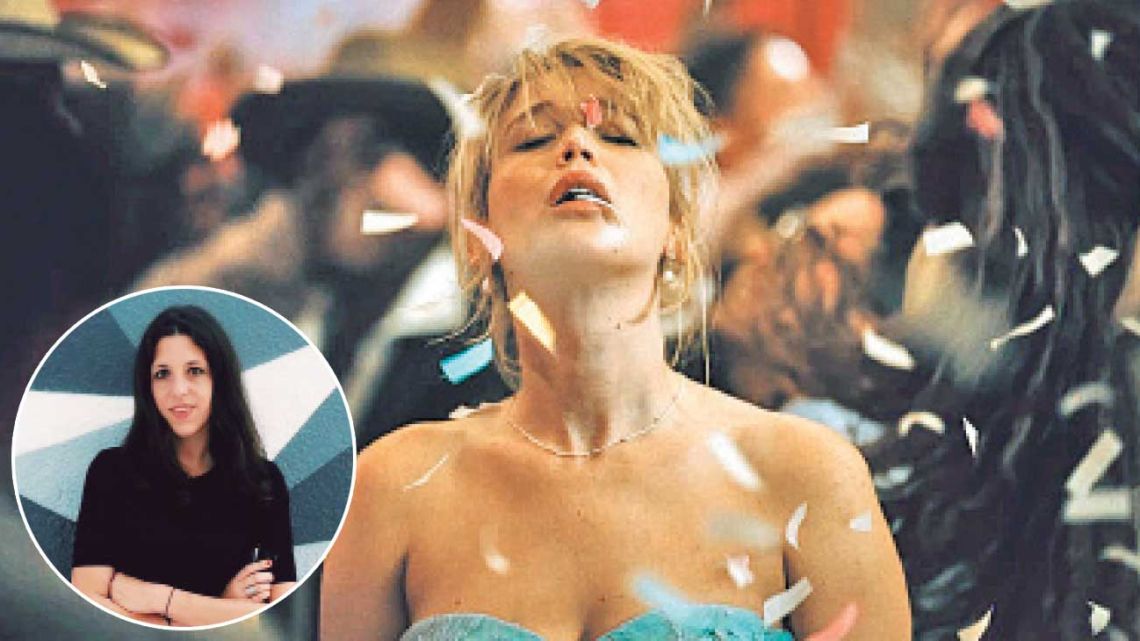

Argentine author Ariana Harwicz speaks as she writes: without concessions, without calculation, without lowering the volume of her thoughts. His participation in the ninth season of “MUBI Podcast: Encuentros” is not just another interview, but the opening of an area that remained in the background for years in his public work: his profound relationship with cinema. As the author of the novel “Kill Yourself, Love,” the basis of Lynne Ramsay’s film of the same name, Harwicz finds in this sonic space the perfect excuse to say, without permission, everything that cinema has done to her as an artist – and continues to do to her.

—What do you personally like about speaking publicly about cinema?

“The truth is that I am very happy because many years ago, since the first novel, this novel we are talking about, I was never able to work in film. I always thought of literature from other frameworks, from other disciplines, other languages. I come from theater, studied cinema, but I had never allowed myself to talk about cinema colloquially, to give vent to my love for cinema. You bring up references, you talk about Cronenberg, Lynch, Casablanca, but I had never really thought about cinema. It’s an adventure.

Authoritarians don’t like that

The practice of professional and critical journalism is a mainstay of democracy. That is why it bothers those who believe that they are the owners of the truth.

—What does this cycle of conversations represent as a cultural object?

“I started to engage more intensively with contemporary cinema. Not just watching films, but systematizing them, opening the library: festivals, Cannes, auteur cinema. And it created a big contrast for me because my training comes from the 20th century. I stayed with the first Scorsese, with the first Herzog.

The rediscovery of the current Duke, who is over 80 years old, gave me a culture shock. I’m not saying it was better before, but it was different. Cinema was thought of from a different place, from photography, time, form.

—Today it seems that the language of cinema is everywhere, but cinema is not.

-Exactly. There is a cinema everywhere and there is a cinema nowhere. The language of cinema has gained language on Instagram, in the stories, but cinema as a medium is in a very complicated place. It is mass art that has suffered the most from the blow of the market. I see it from the inside: which films sell and which don’t, based on political tensions, by country. It lies at the epicenter of current tensions. There is a lot of programmatic cinema, more than ever before. Before the formula should be changed; Now even the change seems to be programmed.

—In this context, what did the experience of “Kill yourself, love” and Lynne Ramsay mean to you?

– I was very lucky. I didn’t do anything to ensure that the book reached Scorsese, that he called Jennifer Lawrence, that she called Lynne Ramsay. I didn’t push, there was no lobbying, no marketing, no ideology. The book arrived alone.

And I fell into the hands of a director who grants nothing. The film is imperfect, but not concessionary. My books are not pochocleros either. There is a similarity between his cinema and my writing. She has set herself a very high goal and it shows.

—What motivates you about cinema?

– The same thing that moves me about a painting, an opera, a story. I get excited when an artist has a vision and that vision makes me see something in a way I’ve never seen before. It’s the vision that inspires. The delivery, the nobility of the delivery. This applies to all languages. The cinema was the first thing that came to mind. I studied film for almost ten years. I’ve seen complete retrospectives, edits, and semiology. Cinema taught me to think about art as a whole: music, images, photography. He taught me transgression, Pasolini, Duke. It formatted my entire head.

Another space for reflection

JMD

MUBI Podcast: Encuentros launched in 2021 as a place for deep conversations about cinema and creation in Latin America. Over the seasons it has brought together personalities such as Gael García Bernal, Marina de Tavira, Ilse Salas, Cecilia Suárez, Julieta Venegas, Dolores Fonzi and Mercedes Morán. In the sixth season, the series is renewed with twelve guests and a clear premise: to think about cinema from experience and not from advertising.

The episode that reunites Ariana Harwicz with Isabel Coixet is in this spirit. There are no closed answers or reassuring speeches. There is thinking out loud, friction, cinephile memory and a critical look at the audiovisual present. Harwicz speaks not “as a guest author,” but as someone who was trained in cinema, was touched by its story and now clearly observes its changes.

At the same time, the latest adaptation of Mátate, amor once again places his work in direct dialogue with contemporary cinema. Lynne Ramsay’s film, starring Jennifer Lawrence, brings the discomfort and power of the original text to the extreme without looking for narrative shortcuts. At this intersection between literature and cinema, Harwicz claims no allegiances: he acknowledges affinities. And she understands that her literature, like the cinema that shaped it, exists to disrupt, to undermine, and to raise questions that seek no resolution.