According to the Art Basel and UBS 2025 Art Market Report, global art market sales in 2024 will reach US$57.5 billion. With 43% of global sales ($24.8 billion), the North American market is the strongest. Experts estimate that illicit money laundering at the global level can be weighted on the basis of global GDP, for the year 2025, calculated at US$113.8 trillion, taking into account the flow of illicit funds between 2 and 5% of it: between US$2,276 trillion and US$5,690 trillion.

What is at stake is more than just a number: it is clear that the total global art market represents only a minimal percentage of the illicit money laundered, with North American funds making up half of this percentage. And of global art, a significant portion – not to mention the majority – of what is sold – complies with current regulations regarding the source of funds and the payment of taxes.

A recent note published by The Conversation says: “Art is traditionally associated with noble motives and heritage. However, the art market, with its high unit value transactions, subjective or manipulated valuations, and relative obscurity, can be exploited as a tool for criminal investment and money laundering, particularly through the purchase and resale of works of art to legitimize illicit money.” Is it that way or are there more interests at play? This is why a series of fingerprints, both informational and legal, must be followed.

Authoritarians don’t like this

The practice of professional and critical journalism is an essential pillar of democracy. This is why it bothers those who believe they are the bearers of the truth.

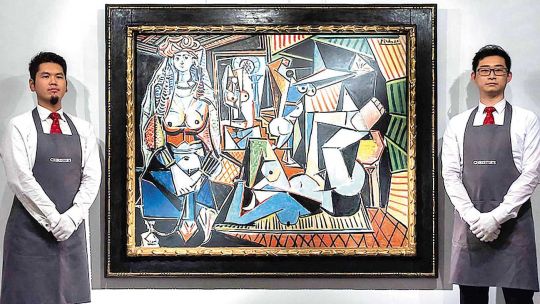

It is understood that the field of art is conducive to money laundering: first, it is a direct source of income through the production of counterfeit works and the sale of stolen objects. Secondly, original works of art are bought and resold to clear the illicit money. The process consists of at least three stages: investment, stratification and integration. Investing involves converting illicit funds into money deposited in bank accounts; Thus, criminals purchase works of art for cash to resell, and demand payment by bank transfer from the new buyer. This is done through bribes to people with inside information in galleries, auction houses or free ports.

Layering: Move invested funds across multiple accounts to hide your tracks. The art market is attractive in this regard because of speculation on certain types of works and auctions, which can lead to an irrational increase in price. This in turn allows large amounts of money to be invested in a limited number of transactions without attracting attention. Finally, integration involves reinvesting the laundered funds into legal assets, often through shell companies, to complete the cycle.

In February 2013, the European Commission approved rules requiring art galleries to report anyone who pays more than €7,500 in cash (about $9,825) for a work and to file suspicious transaction reports. Around the same time, the United States required reporting of all cash transactions of $10,000 or more. But this seems to be lacking, at least that is what is expressed in the statement of Transparency International USA, a North American organization demanding more controls on the art market because it “undermines national security,” giving some examples of money laundering such as: “In 2020, a bipartisan Senate investigation discovered that oligarchs linked to the Kremlin used intermediaries and anonymous transactions in the American art market to move more than $18 million, evading sanctions and exploiting sanctions.” In the sector, American auction houses and sellers facilitated the purchases of Teodoro Obiang Mang, the former Vice President of Equatorial Guinea, who laundered hundreds of millions of dollars in corruption. After a lengthy lawsuit, the United States obtained the forfeiture of $30 million in assets located in the United States (including famous pop culture collectibles). American galleries and auction houses were used to acquire works of art, including works by Van Gogh and Monet, while embezzling funds from the country. Malaysia’s sovereign investment fund, 1MDB (1Malaysia Development), is exploiting US markets to launder part of a multi-billion dollar corruption scheme.

These examples defend the bipartisan Art Market Integrity Act, which would amend the US federal bank secrecy law to cover certain intermediaries in the art market who, according to its proponents, enjoy privileged status, such as dealers, galleries and auction houses.

As for cultural property news, this project relies on the Antiquities Coalition lobby, which has issued wildly false reports confusing the legal market for antiquities with the market for criminal activity. They even back up their rhetoric about companies providing anti-money laundering services, such as AML RightSource and The ArtRisk Group, exaggerating links between the art market and terrorism.

Another criticism from the same source: The emerging law is “a Trojan horse that uses the language of financial crime to advance deep-rooted ideological goals aimed at eliminating the antiques trade. By conflating art and antiques, criminalizing legitimate market conduct and imposing costly compliance burdens, the bill threatens not only dealers but also museums, collectors and researchers.”