The time ended when a Latin American writer, eager to publish, moved to Barcelona to build a house among the major Catalan publishing houses. If it is broken a new one Boom Literary work, it is likely to be the first in the American continent. The push for independent Latin editorials and the expansion of literary agents in the region, along with English translations and the promotion of festivals, was redeployed over two decades, and a Spanish-language literature scene emerged. Barcelona maintains its voice and economic weight, but the literary dialogue stops in Mexico City, Bogotá, Buenos Aires, or New York. “There is no need to go back,” summarize Ana Lucia Barros and María José Ojeda, publishers of the Colombian magazine Laguna Libros.

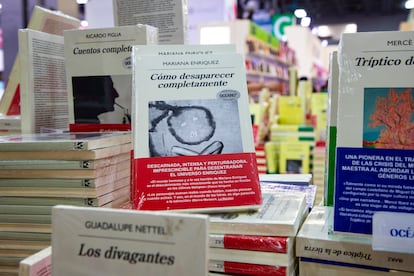

The result is a mosaic far more complex than the one that triumphed in the masculine canon of the 1960s and 1970s, and whose last proponent, Mario Vargas Llosa, died this spring. “So there was no such smooth communication between Latin American editorials. For an Argentine, Chilean or Mexican author to get to Colombia, they had to first be published in Spain,” adds Barros, whose distribution in his country is to big names such as Mariana Enríquez, Maria Gienza or Fernanda Trias, which is published by Anagrama and Penguin Random House in Spain and other Spanish-speaking countries. It is these small and medium-sized editorials that in many cases acknowledge literary quality, before authors win out and jump into larger collections.

The disparity between publishing houses reinforces the increasing fragmentation in the sale of rights. “There is work to train literary agents and their editors on how to buy and sell rights, something that was completely unknown,” says Nobia Macias, former director of Planeta Group in Mexico, the United States and Central America, and executive director of FIL. “Before 2000 or 2001, the editor forced the author to sign a lifetime contract, in all languages and in all styles.” That’s it. At the same time, Macías adds, “good book fairs are emerging and growing, as in Guadalajara, which opens up the rights market.”

There are more actors demanding a space at the table and not all of them are in Spanish-speaking countries. New York is home to some important acting agencies, such as Indent Literacy Agency – made up of a Colombian, Spanish and Guatemalan community – and NYU houses the Mastery of Literary Creativity that sells many writers in the region. The Booker Prize or National Book Award is complemented, thanks to English-language translations, that serve to highlight Latinx authors internationally, with Argentine Gabriela Cabezon Cámara as a recent example, who has just won the National Prize with the English version of Narangel girls (Random House, 2023): We are green and trembling (New Directions, 2025).

However, amidst this fragmentation, Barcelona’s thriving industry continues to bear a burden that is difficult to cope with. 65% of editorial sector invoices in Latin America belong to companies based in Barcelona or Catalonia, according to the Spanish city council. This proportion includes local branches of major corporations, acting independently but in coordination with the head of each seal, which have gained primary weight. “It’s an important fact because you have to see a little with who decides what you read,” says Guillermo Quijas, managing editor of the Mexican newspaper Almadia, who decided to open a branch in Madrid, although it is in Barcelona where he has built more relationships. “We also try to be here to make certain decisions about what can be published and what will be read,” he says.

Materialism ha hecho el jiji is the opposite of the industry. While large Spanish groups opened branches on the American continent, this small Oaxaquina-based editorial decided to cross the pond to distribute in Spain to Latino authors, who account for 70% to 80% of its catalog and sales. He publishes about 14 books on both sides of the Atlantic, plus three or four individual books in Mexico. Some of its authors came from the Literary Creativity course that his native Juan Pablo Villalobos was teaching in Barcelona, such as Vicky González or Mariantoa Correa. As with the New York initiatives, this cycle, as Pompeo Fabra’s mastery of literary creativity, serves as a mine from which to extract future literary successes.

“Our experience with the teacher is that Barcelona is still a bridge between the two shores. He is in Uruguayan Yog Ladra and Chilean Andrés Montero, who was our students. And Villalobos, who is our soap opera teacher. Latin American composers are often known in Barcelona, because it is a space of convergence,” points out Jorge Carrión, writer and co-director of graduate studies, who believes that he is in a “special place” An interesting moment in the transatlantic relationship, with the new Gabriel García Márquez Library, and the activity The “feverish” work of Latin American bookstores Lata Peñada and La Malinche, the theatrical adaptation of Latin American books by Casa América Catalunya, and the recent long-term visits of María Negroni, Cristina Rivera Garza, and Alan Boles.

Also in Barcelona is the important literary agency Casanovas & Lynch, which represents such prominent names as the Mexicans Jorge Volpe and Dalia de la Cerda, the Argentine Andres Newman or the Colombian Fernando Vallejo. A huge current account seems to exist among Spanish readers: while the peninsula’s industry is opening up to Latin America, the large readership continues to look inward. Latin American books represent about 50% of Penguin Random House’s Spanish catalog. However, these authors’ sales in Spain represent roughly 1% of what the country’s publishing house releases, a tiny percentage that breaks down the gap that generates some superior sales.

This is a fundamental difference in the era in which Gabo or Bolaño triumphed, says Pilar Reyes, managing editor at Random House. “the Boom It was a reader phenomenon. How can we rebuild this? This is the challenge,” he admits. “When we talk about the market, about the book industry, we are finally talking about readers, about cultural relationships and dialogues,” he also means, by maintaining diversity in the catalogues, despite the disparity in sales: “Editorial plans must be a midpoint between the commercial logic and the cultural logic.”

In this scenario, the Anagrama editorial presents some names that are also causing a stir in the Iberian Peninsula, especially in the narrative, such as the Argentine Mariana Enriquez or Benjamin Labatut, the Chilean Alejandro Zambra or the Mexican Guadalupe Nettle, says the group’s editorial director, Silvia Ceci. “These authors sell very well in Spain,” he confirms. Authors’ paths to these publishing houses are varied. Sometimes their writers seek them out, other times they seek out recommendations from other authors or literary agents, and there are also occasions when they approach them after winning some local independent editorial.

Among this type of opening, the dialogue is more flexible, regardless of the country of origin. Traffic, Barret or Las afueras stands out among Spaniards who bet on Latin American titles before they spread among the mass public. The last phenomenon of the Phaguara cometera, The Argentine Dolores Reyes is a good example of this rise, which began with Siguilo’s editorial, in 2019, in both Argentina and Spain.

“I had some valuable offers at Lata Peinada, and I went to the BCNegra Festival, which for me was a before-and-after event. It was my first time leaving Argentina, and it was presented to a large number of people. They read the book, and if they hadn’t, they bought it, they were interested in it. It left me with such a beautiful experience with my book that I got it all el cariño del mundo,” says Reyes, who considers the Catalan capital still a delight to the world. Corona: “It is still very, very important.”