The beaver who would one day be named June was simply doing what beavers do. But his dams, built around his den in Utah’s Bear River Mountains, displeased a rancher. He said the floods had stuck his sheep in the mud.

This placed the furry engineer in the “problem beaver” category. In most of the United States, she would have been killed. Instead, she was recruited: strategically moved and released with the goal of restoring degraded waterways elsewhere in Utah.

Beavers have a unique drive to slow the flow of water and create ponds, with abilities to match. In the western United States, animals are increasingly valued for their ability to retain water in a dry landscape.

Its dams reduce runoff, recharge groundwater, create habitat for fish and other wildlife, help streams collect critical sediment, and create watering holes. As wildfires intensify, beavers are more important than ever.

But their rodent and dam-building activity has long caused them problems with humans. And that hasn’t changed.

Utah is one of many states, tribes and conservation groups leading the nation in relocating unwanted beavers. Although the animals remain controversial, Teresa Griffin, wildlife manager for the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, said she is seeing more interest than ever from her colleagues.

“At first we were just doing it in the southwest corner of the state, but now everyone is jumping on board and becoming a beaver believer,” Griffin said.

Experts emphasize that it is better to find ways to coexist with beavers rather than relocating them, as this poses significant risks to the animals. Devices can help, including some that prevent water in dams from rising too high and others that protect culverts and drains. The right type of fencing around the trunks can protect the trees.

“Education should be the No. 1 priority,” said Shane Hill, who has worked on beaver restoration at the State Wildlife Agency and the Sageland Collaborative, a nonprofit group.

Yet when landowners are determined to eliminate beavers, relocation gives the animals a second chance.

Utah requires beavers to be quarantined for at least 72 hours before being moved to a new watershed to prevent the spread of aquatic invasive species and disease.

Beavers therefore need accommodation.

At Griffin’s Southwest location, customers use two donated hot tubs, now filled with cold water. To the north, outside Logan, the Beaver Bunkhouse offers concrete pools.

June ended up at the inn.

Upon check-in, beavers are inspected for injuries, weighed, microchipped and named.

There is also a surprising procedure for identifying your gender, which is impossible to discern from the outside. Not to go into detail, it involves pressing on a gland, feeling it and checking its color.

“It’s really interesting,” said Becky Yeager, facilities manager for the Beaver Ecology & Relocation Collaborative, created by Utah State University and which manages the Bunkhouse. “But it’s important for us to know the gender.”

Beavers mate for life and families maintain close bonds. Animals are more likely to stay in a resettlement location when they are moved together, so team hunters attempt to capture as many members as possible. With solitary beavers, the group attempts to release males and females into a given area.

“It gives us the opportunity to play matchmaker,” Yeager said.

Beaver wetlands once covered North America, helping shape the continent’s hydrology. But by the late 1800s, the fur trade nearly wiped out the animals. Statewide reintroduction efforts followed, including airdrops into Idaho in 1948. Today, biologists estimate that perhaps 15 million beavers live in North America, compared with a historical figure of perhaps 100 million or more.

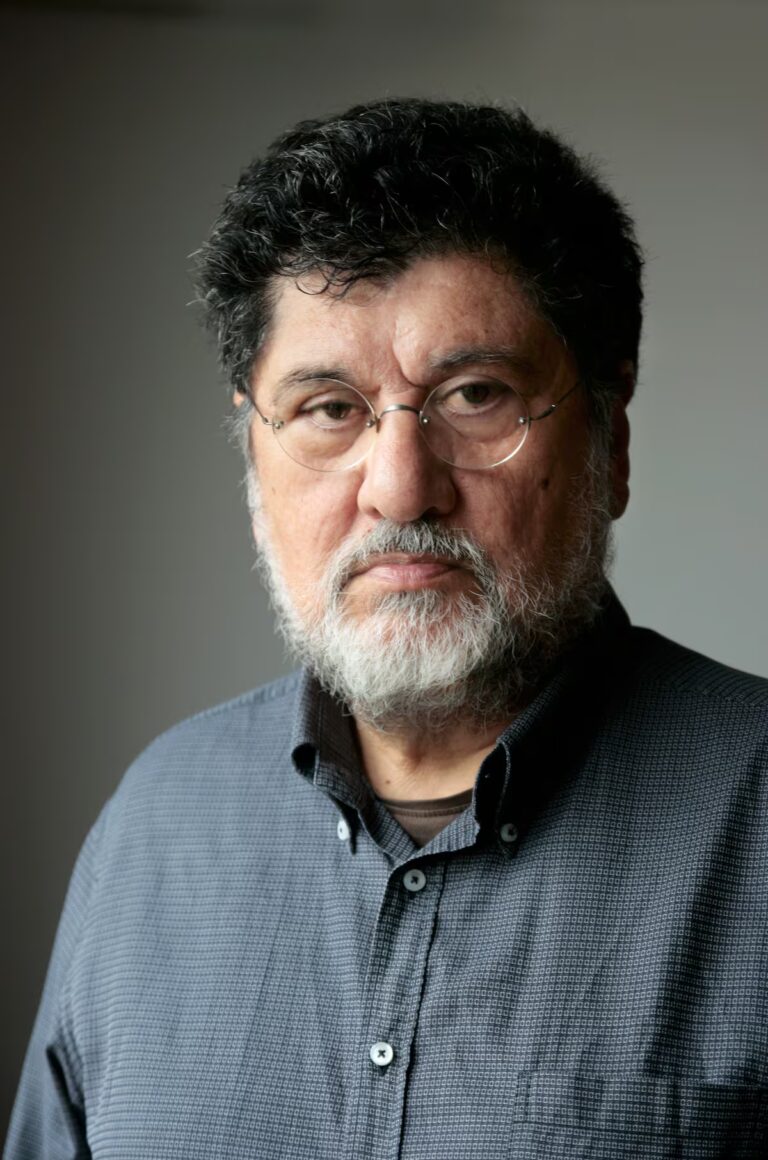

Nick Bouwes, an aquatic ecologist who helped launch the collaboration at Utah State University, arrived at the beaver resettlement through his own landscape-altering efforts. He and his colleagues were building dams mimicking those of beavers to try to restore waterways, encouraging the animals to take on the work, he said. Soon after, the beavers did.

“I started to see what beavers could do and how fast they could do it,” Bouwes said. “Our structures were just — we’re just kids playing in the sandbox compared to what they’re doing.”

Today, the group traps and releases about 60 beavers a year, working with the National Wildlife Agency’s northern office. The south office is moving about 30, and the central office has gone from single digits in recent years to 26 this year.

Hundreds of other Utah beavers, problematic or not, are killed by hunters. In the United States, the federal government has killed more than 23,000 people in 2024.

Northern Utah trapper Ambrie Darley used to trap beavers with deadly devices similar to giant rat traps. It’s much easier that way, she says. But in 2021, she and her late husband began working with the university collaboration on live trapping beavers.

“I’ll be honest, it’s really transformed us,” said Darley, who no longer fatally traps beavers. “I find it very rewarding when something can be useful elsewhere,” she says.

The beavers that have the most problems are usually young, single people who have recently left their families, said Nate Norman, chief biologist at the Beaver Ecology & Relocation Collaborative.

“They’re looking for a mate and a new home and they wander onto someone’s property and start cutting down trees,” Norman said.

When relocated, the biggest question is how the animals behave after release. The national wildlife agency and the beaver collective have tried to find their former charges by placing radio transmitters in their tails, but the animals tend to get rid of them quickly. Groups have moved away from this approach.

Generally speaking, research has shown that relocated beavers are at significant risk of being killed by predators such as cougars and bears. And it can be difficult to convince them to restore a specific area, as they often choose to leave the release site.

Norman thinks success rates have a lot to do with placing beavers in the right habitat: not so degraded that they can’t survive, and not too crowded with other beavers, since the animals are territorial.

He is working with two biologists, Alex Fortin and Natalie D’Souza, who are testing a new method of tracking beavers after their release, which involves analyzing satellite images.

This project is only half complete, but it has some encouraging stories.

Initial searches led the team to find a few beavers, including none other than June. It had been captured in 2022 and released in the Raft River Mountains, where state biologists hoped the beavers would, among other things, create habitat for Yellowstone yellow-throated trout.

Three years later, D’Souza and Fortin discover that June had started a family and widened a creek.

On a field trip, they found a group of fishermen fishing in new lakes created by the beavers. One by one, they fished for Yellowstone trout.