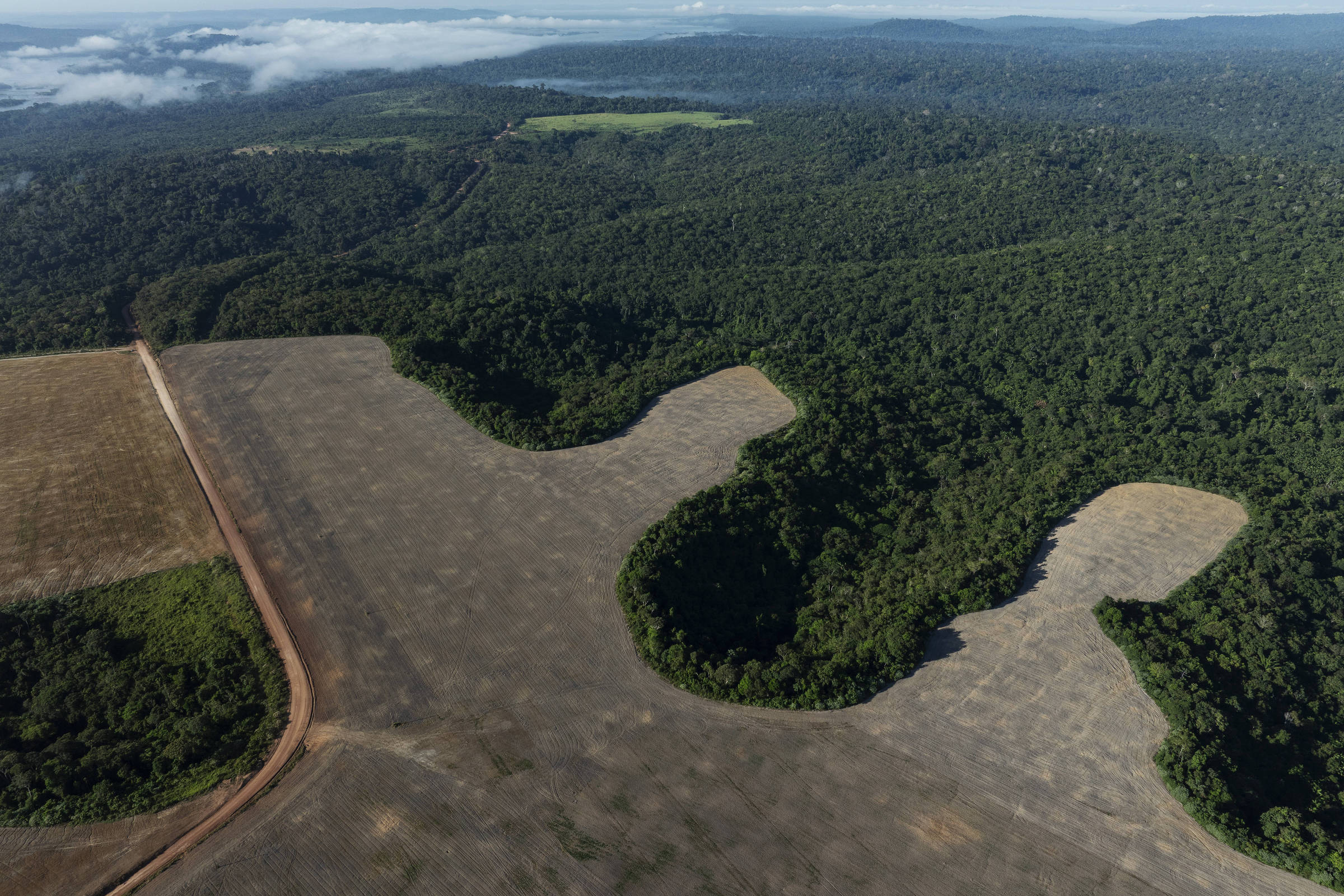

Brazil will need to quadruple the current pace of forest restoration to meet the goal of recovering 12 million hectares by 2030. If it is to keep its promise, the country will need to restore, in each of the next five years, an area equivalent to 11 times the city of São Paulo or 14 times the city of Rio de Janeiro.

The vegetation target has existed since the first Brazilian NDC (acronym in English for nationally determined contribution, as each country’s target is called in the Paris Agreement). The document entered into force in September 2016.

The MMA (Ministry of Environment and Climate Change) indicates that 3.4 million hectares were being restored by November 2025. Thus, since the target was set, only 28.25% of the promised area is being recovered.

It would therefore be necessary to restore 1.7 million hectares, or 17 thousand km2over each of the next five years, to fulfill the commitment

On average, Brazil has recovered 380,000 hectares per year since 2016, according to the report’s investigation based on MMA data. The country will therefore have to quadruple this rate.

Leonardo Sobral, director of forests and forest restoration at the NGO Imaflora, says Brazil has struggled to break out of its inertia and begin restoration actions.

“This objective has been set since 2016, and what did we do in 2017, 2018? Practically nothing, the country took time to understand that this is really an important agenda for development, for environmental but also social issues, for job creation,” he said. “We have reached this result today, which is undoubtedly very weak and which must be accelerated.”

MMA Biodiversity, Forestry and Animal Rights Secretary Rita Mesquita says updates on the country’s restored areas will be released every six months. “I haven’t seen us reach a third since 2016. Once we defined a methodology, we managed to reach a third of the target in the first year of monitoring.”

Conaveg (National Commission for the Recovery of Native Vegetation) approved this year the parameters that will guide the monitoring of the objective.

Paulo Amaral, senior researcher at Imazon (Institute of Man and the Environment of the Amazon), says the country is falling short of its goal. “This is well below the existing potential and the objectives that can be achieved quickly and even simply, if we consider secondary vegetation (that which returns naturally after the destruction of an area).”

He affirms that the deficit of forest areas to be restored reaches 23 million hectares, including 14 million in the Amazon.

On a linear scale, without accelerating the current pace, Brazil will arrive in 2030 with around 5.3 million hectares recovered, or only 44% of what was promised.

Rubens Benini, director of forests at The Nature Conservancy, notes, however, that restoration is happening at an exponential rate and believes that actions should accelerate in the years to come. “At the time, no one knew how to do restoration, the capacity for execution and implementation was minimal,” he believes.

“Today there is money, there are already cutting-edge institutions that operate with quality. We have to convince the landowner and we are fighting for that,” he says. “Now that we have a more organized home, there’s no reason not to take the plunge.”

According to the portfolio of Minister Marina Silva, 52% of the area already restored in the country (1.77 million of the 3.4 million hectares) corresponds to the secondary vegetation of indigenous lands and conservation units, that is, forests that progress naturally and spontaneously.

“These areas shouldn’t even have been deforested, because they are already protected. So this is the government looking at its backyard, which it hasn’t taken care of, and now offering this as an offer,” Amaral explains.

The secretary of the MMA affirms that the restoration of these territories is the result of deintrusion processes carried out by the public authorities.

The Planaveg (National Plan for the Recovery of Indigenous Vegetation) determines that 9 million of the 12 million hectares will be obtained through the recovery of legal reserves, areas of permanent preservation and restricted use, all provided for in the Forest Code. According to official data, these categories total 1.2 million hectares under restoration on rural properties with the CAR (Rural Environmental Register) validated, or around 13% of what had been promised.

Mesquita argues that it is necessary to identify restoration intent in order for a certain area to be included in official statistics. “I cannot begin to count as regular a property whose CAR has not yet been validated. As long as the CAR is not validated, it does not enter into the regular land statistics,” he declares.

“But, in the Brazilian landscape, we already have well over 12 million hectares under restoration, in the most diverse biomes,” he also underlines.

Sobral, from Imaflora, believes that the 2030 target is achievable, but expresses concern about changes in the country’s political scenario. “Forest restoration is not just about planting trees. We are talking about an expensive process, which takes years, and maintenance is even more important than planting.”

Researcher Ane Alencar, scientific director at Ipam (Institute for Environmental Research of the Amazon), says that the scenario is difficult because there are cases of restoration projects strongly affected by climate change and fires. “People working on planting seedlings, for example, report that they have suffered a loss of 20 to 40% due to drought (in 2024).”

The Restoration Observatory, led by the Brazilian Coalition for Climate, Forests and Agriculture, centralizes information collected from businesses, governments and social organizations that develop restoration projects.

Data released on the 10th indicates that 204.2 thousand hectares are being restored in the country. The Atlantic Forest represents 64% of the total, followed by the Amazon (19%) and the Cerrado (15%). Caatinga, Pantanal and Pampa represent only 0.7% of the areas being recovered.

This figure differs from the 3.4 million hectares recorded by the MMA because it only takes into account projects self-declared by organizations, while government data involves satellite measurements.

Tainah Godoy, executive secretary of the Observatory, says that the beginning of the 2020s served to prepare the foundations for the reconstitution of forests. “The first five years of this decade were about organizing the restaurant chain, talking about and spreading the word about what catering is and its many benefits.”

“I believe that from now on, from the middle of the restoration decade, until 2030, growth will tend to be stronger and more vigorous.”

According to the Observatory, civil society organizations represent 40.5% of the 204 thousand hectares under restoration, while the private sector contributes 32.9%. Governments are in third place, with 18.3%.