Breast cancer cells alter the diurnal (day-night) rhythms of corticosterone levels. In doing so, they modify the behavior of neurons and promote the establishment of cancer in the body.

This was found in a study published in the … ‘Neuron’ magazine produced by a team from Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

Corticosterone is the main stress hormone in rodents. In humans, it is cortisol. Normally, levels rise and fall naturally throughout the day. In the case of breast cancer, the team discovered that tumors inhibit the release of corticosterone, thereby reducing quality of life and increasing mortality.

“The brain is an exquisite sensor of what’s happening in the body,” says Jeremy Borniger, associate professor at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. “But it requires a balance. Neurons must be active or inactive at the right time. If this rhythm becomes even slightly out of sync, it can impair the functioning of the entire brain.

Disruptions to our own diurnal rhythms have been linked to stress responses such as insomnia and anxiety, both common in cancer patients.

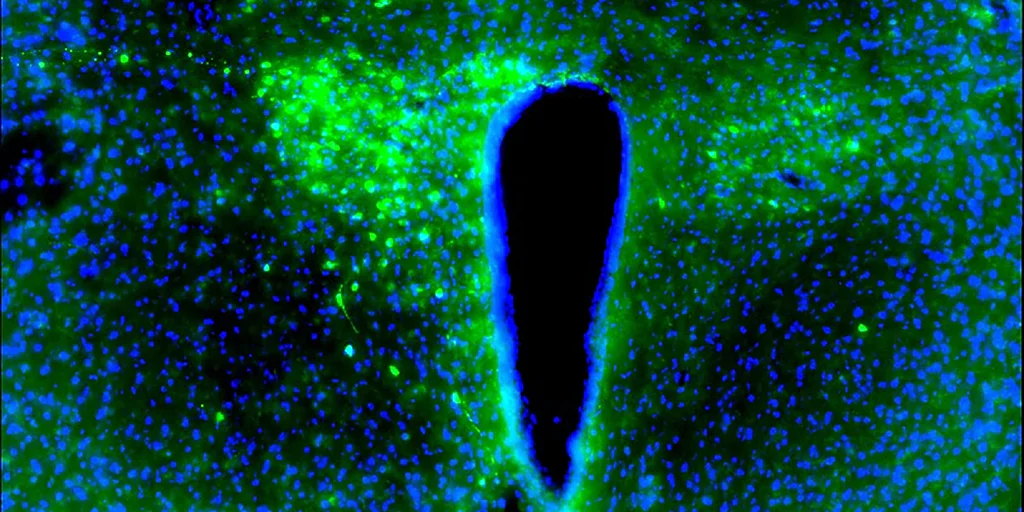

The body relies on a feedback loop called the HPA axis to maintain healthy levels of stress hormones. The hypothalamus (H), pituitary gland (P), and adrenal glands (A) work together to ensure regular rhythms between day and night. Borniger was surprised to find that, in mice, breast cancer can disrupt these rhythms before the tumors take hold: “Even before the tumors were palpable, we saw a 40 to 50 percent decrease in this corticosterone rhythm,” he said. “We could see that this was happening within three days of the cancer appearing, which was very interesting.”

When the team looked at the hypothalamus, they found that key neurons were locked in a hyperactive but underproductive state. Once the team stimulated these neurons to mimic the mouse’s normal day-night cycle, the regular rhythms of stress hormones resumed. This adjustment pushed cancer-fighting immune cells toward the breast tumors, causing them to shrink significantly. Borniger explains:

Applying this rhythm at the right time of day increased the immune system’s ability to kill cancer, which is very strange, and we’re still trying to understand exactly how it works. What is interesting is that if we apply the same stimulation at the wrong time of day, it no longer has this effect. It is therefore really necessary to maintain this rhythm at the right time to obtain this anti-cancer effect.

The team is currently studying how tumors disrupt the body’s healthy rhythms. Borniger hopes his work could one day help strengthen existing therapies.

“What’s really cool is that we didn’t treat the mice with cancer drugs,” he says. “We make sure the patient is as physiologically healthy as possible. That, alone, fights cancer. This could one day help increase the effectiveness of existing treatment strategies and significantly reduce the toxicity of many of these therapies.”