Canada and Mercosur are seeking a free trade deal by the end of 2026, at a time when U.S. protectionism is boosting efforts by other countries to deepen cross-border trade.

Amid aggressive tariffs from Washington, which included measures targeting Canada and Brazil, the two sides restarted negotiations on a possible deal in October.

This rebound began a process that began in 2018, when Canada, in particular, faced similar trade turmoil under the first administration of Donald Trump. These conversations were interrupted three years later, in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic.

“Together with our partners, we are actively working to conclude these negotiations next year,” said Canadian International Trade Minister Maninder Sidhu, who visited Brasilia in August.

This objective was confirmed by two other officials from countries involved in the negotiations who spoke to the Financial Times.

Mercosur includes Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay, with Bolivia in the process of becoming a full member. The group has major producers of agricultural and mineral commodities, including soybeans, crude oil, iron ore and beef among its main exports.

Although Brazil’s bilateral merchandise trade with Canada is by far the largest in the Mercosur bloc, totaling US$12.7 billion in 2024, it represents only a small fraction of the more than US$760 billion in goods traded between Canada and the United States.

Trump’s mercantilist “America First” trade policy has been a factor in revitalizing the Canada-Mercosur deal, two officials with knowledge of the discussions said.

Ottawa has been hit by tough U.S. tariffs on highly integrated cross-border industries, including lumber, steel, aluminum and the auto sector. Washington also imposed a 50% import tax on Brazil in 2025, but has since removed tariffs on several Brazilian food products.

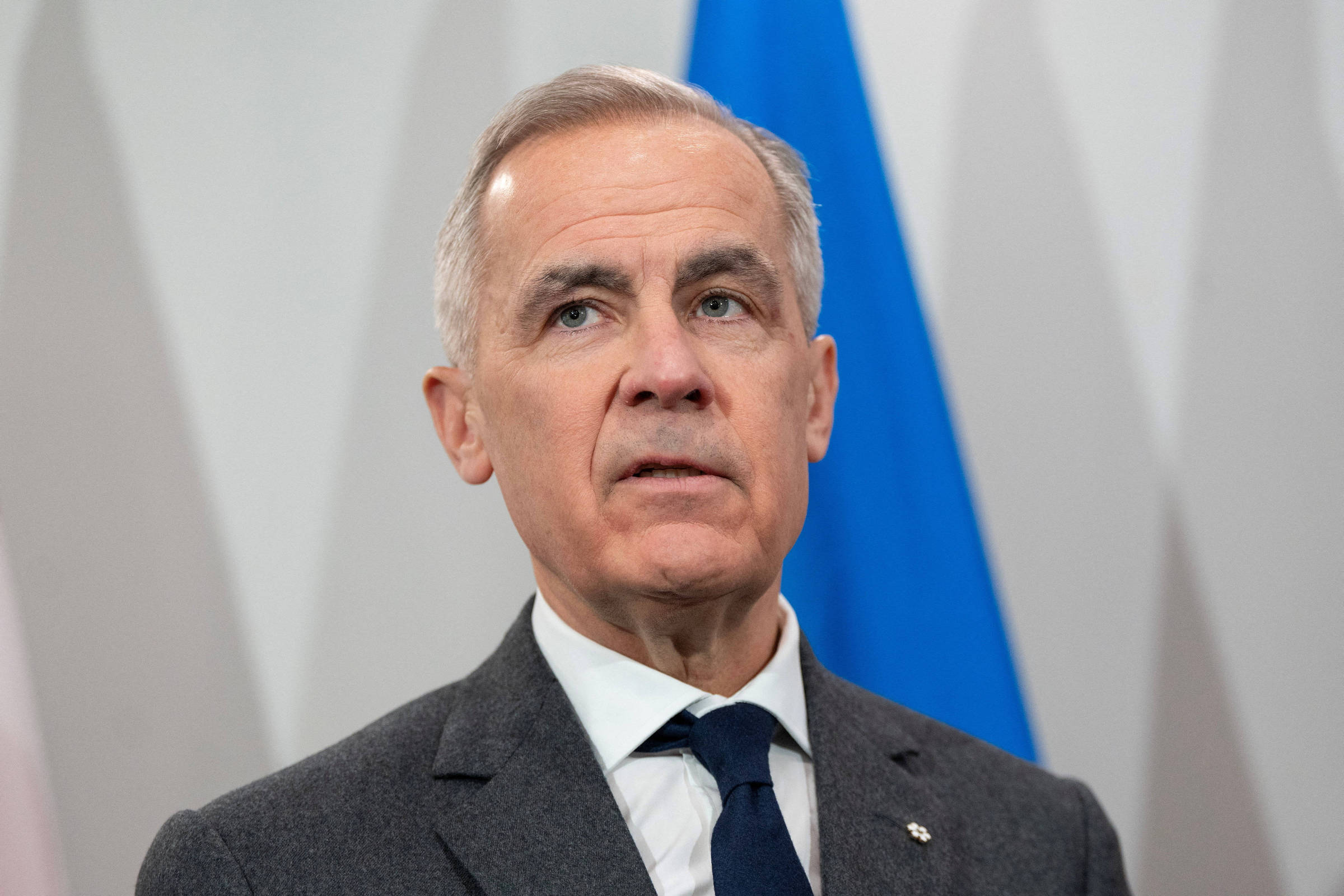

Canadian Industry Minister Mélanie Joly told the FT the country was seeking new deals around the world, such as with Mercosur, in a bid to diversify outside the United States.

“We have a lot of these deals that are good on paper, but our companies aren’t necessarily exporting to these different jurisdictions, these different markets, so we need to do more,” she said.

But some observers were skeptical about a potential Canada-Mercosur deal, given the overlap in exports and the tendency to prolong trade negotiations.

Barry Appleton, a Toronto-based international trade lawyer, said Canadians have been “very slow” to take advantage of significant market opportunities in Latin America.

“One of the problems is that Mercosur and Canada are competing to trade many of the same primary products in global markets,” he said.

The negotiations aim to introduce zero tariffs on most products, said a person directly involved in the discussions. Since a meeting between top negotiators in October, working groups have addressed specific topics, including tariffs, small and medium-sized businesses and anti-dumping, they added.

“There is a video conference almost every day,” said the official, who requested anonymity, adding that more in-person conversations are expected in early 2026.

Another employee said: “The priority is to get something viable quickly. It doesn’t have to be exhaustive. »

The long-awaited free trade agreement between Mercosur and the EU was due to be finalized in December, but was postponed again following protests from European farmers. Brussels has said it hopes to sign the deal in January.