Chileans will vote this Sunday in the second round of the presidential election, which could lead to the biggest shift to the right in the South American country since the end of the military dictatorship in 1990.

Nearly 15.6 million registered voters in Chile are expected to vote. Polling stations will close at 6 p.m. (Brasilia time), depending on the flow of voters, and the first results are expected shortly after.

The second round pits José Antonio Kast, from the far-right Republican Party that he founded, against Jeannette Jara, candidate of the current left-wing government coalition, belonging to the Communist Party.

Although Jara won the first round in November with 26.85% of the vote, Kast beat several right-wing candidates to come in second with 23.92%. The majority of voters who supported these candidates are expected to vote for Kast, giving him more than 50% of the vote and the presidency.

CLOSING CAMPAIGNS WITH A FOCUS ON CRIME

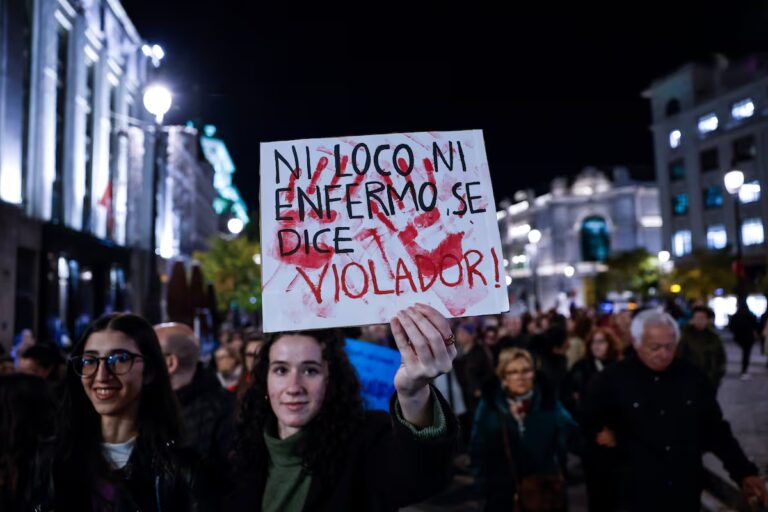

As the campaign drew to a close, the two candidates traded barbs, but also focused on the main issue that defined the election: crime.

Speaking Thursday behind a transparent protective barrier in the southern city of Temuco, capital of a region rocked by conflict between indigenous Mapuche groups and the government, Kast described a country plunged into chaos and said he would restore order.

“This government has sowed chaos, this government has sowed disorder, this government has sowed insecurity,” said the 59-year-old lawyer. “Let’s do the opposite, create order, security and trust.”

Although Chile remains one of the safest countries in Latin America, a recent increase in organized crime and immigration has alarmed the electorate and become a major concern among voters.

The issue quickly became a thorn in the side of left-wing President Gabriel Boric, who rose to power on a wave of progressive optimism following widespread protests against inequality and a promise to draft a new constitution.

Boric, who is not up for re-election due to the ban on consecutive presidential terms, has adapted quickly, increasing funding for the police force, creating task forces dedicated to combating organized crime and sending military personnel to the country’s northern border with Peru and Bolivia.

But that wasn’t enough for many voters. Boric has faced low approval ratings, while Kast’s tough proposals on crime and immigration have attracted support.

“This country needs important reforms, we must return to the path we followed for decades because we are completely lost,” said José Pinochet, a 55-year-old lawyer, as he shined his shoes on a street in Santiago.

Antonia Moreno, 21, said she would vote for Jara but didn’t think she had a chance of winning.

“Unfortunately, we will be one of those countries where the far right will gain ground in Congress and the executive branch,” she said.

CONSISTENT HARD LINE

A victory for Kast will likely be celebrated by investors, who hope a market-friendly government will accelerate economic reforms, including deregulation and changes to the copper-rich country’s pension system and capital markets.

The Chilean peso strengthened and Chile’s MSCI stock index soared after first-round results last month. Although no clear majority emerged in the Senate or Congress in this vote, Kast is expected to eventually pass some economic reforms if he wins the runoff.

“Third time is luck,” he said in a speech after securing his place in the runoff in November. This is his third bid for the presidency and his second run, having lost to Boric in 2021.

Many of Kast’s views were deemed too extreme by voters in 2021, but they are now finding greater receptivity among an electorate hungry for security and tired of traditional political parties.

“I consider the expression of the right, the far right, as a safety valve for the rejection of politics in Chile,” said Marta Lagos, analyst, public opinion researcher and founding director of Latinobarómetro.

This is the first presidential election subject to a law on compulsory voting, with automatic registration for those over 18 and fines for those who do not vote. The change adds an element of uncertainty, with opinion polls showing around 20% of voters are still undecided or saying they will leave their vote blank.

“There is a percentage of voters who do not feel comfortable either with Jara or with Kast,” said Guillermo Holzmann, a political analyst at Valparaíso University. “The question is: who favors these blank or invalid votes?”

At his campaign closing event Thursday in the northern city of Coquimbo, Jara promised to be tough on crime, stressed the need for strong social programs and urged people not to let their vote go empty.

“Talk to people who are considering voting blank. The stakes are high and we must move forward, not backward,” said the 51-year-old lawyer and former labor minister in the Boric government.