When I go out into the street these Christmas days, the memory of Charles Dickens escapes from the library, enters the elevator and accompanies me through the city. Literature, like personal libraries, constitutes a single book, and memories come and go through memory. María Zambrano taught me that writing serves to socialize solitude, and Dickens helps me to become aware of all the solitude that inhabits the songs and the tumults of the party. A crowd, Baudelaire also said, can be a set of solitudes. Store windows, the hustle and bustle of stores and restaurants, Christmas menu prices for business meals, television commercials and holiday lights are filled with beggars. Poverty is there, like a scar on all shared joy, asking for alms for the love of God. To complicate matters further, they also begin to beg for the most intimate memories, the hospital corridors, the losses, the distances and the hours of cover and silence in a defenseless house.

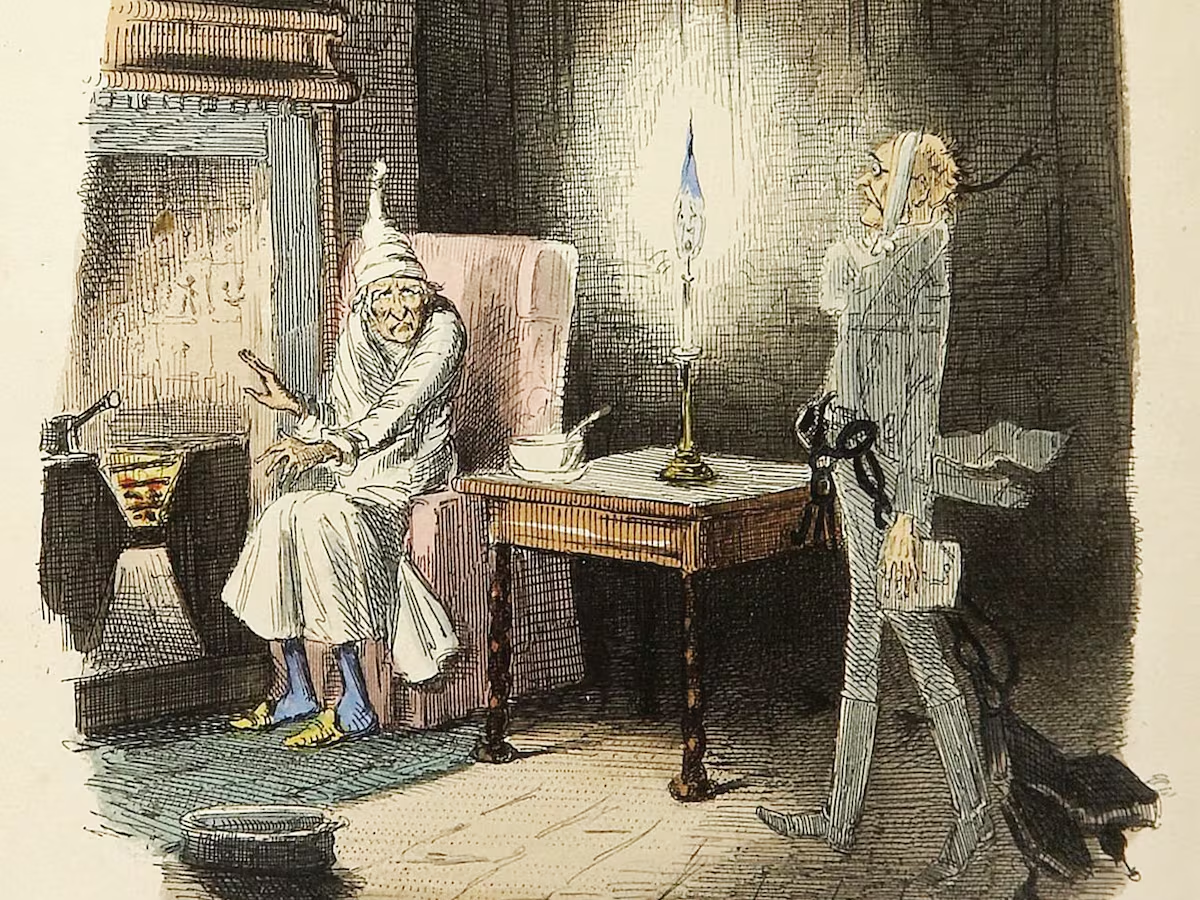

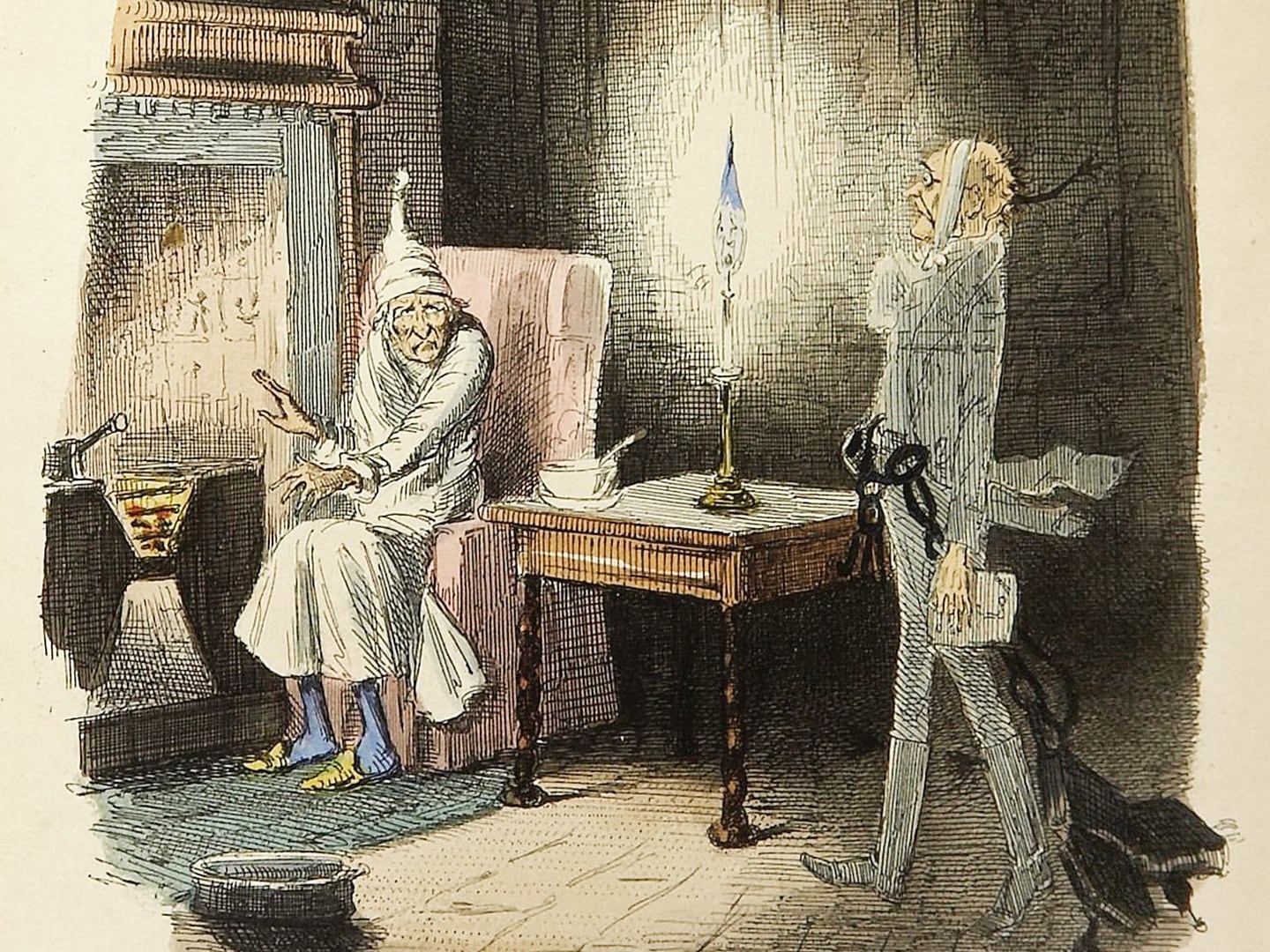

This is why it is appreciated that Dickens’s imagination accompanies us with his Christmas story. The noise of the parties becomes a believable human song, he comes home, goes upstairs and sits with us in the library. It is possible that the miser, the aggressively obsessive coin counter, will wake up tomorrow ready to help the sick child who is dying in a hospital for lack of resources. And it will be possible for the miser to abandon the possessive solitude of his riches to share the table of the people, the bread and water of the most needy, as the child Jesus did when reality transformed him into Christ. My imagination, which is no longer that of Dickens, also invites me to experience a more sophisticated Christmas carol. It will be the needy who will understand the miser’s evil and refuse to sit at his table.