Credit, REPRODUCTION

-

- author, Edison Veiga

- To roll, From Bled (Slovenia) to BBC News Brasil

-

-

Reading time: 7 minutes

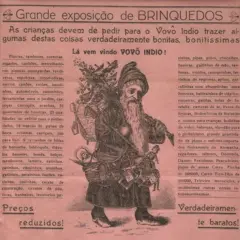

In the 1930s, a character made the headlines in Brazilian newspapers during the Christmas period: Grandfather Índio.

He was a character who worked hard to become popular and dethrone Santa Claus in the hearts of toy-hungry children.

“Grandfather Índio and the children” made the cover of the newspaper The globe on December 24, 1932, with the indication that the character was responsible for delivering gifts to a municipal school in Rio.

The same newspaper published, on November 28, a veritable manifesto in favor of Grandfather Indio – under the title “Let’s have a Brazilian Christmas?” — and, on December 20, a declaration of war on the good old man — “For the deposition of Santa Claus”, such was the name of the text.

In the capital São Paulo, the atmosphere was no different. In 1935, as O Estado de S. Paulo reports, it was grandfather Índio who brought gifts to the orphans of São Paulo as part of an action promoted by the Public Force – the institution that preceded the current Military Police.

In the 1930s, there was also a national competition to choose the image that best represented the character. And, in 1939, a children’s play presented in Rio promoted the unusual meeting of Santa Claus and Grandma Índio.

President of Brazil from 1930 to 1945 and from 1951 to 1954, Getúlio Vargas (1882-1954) had sympathy for this character, researchers attest.

There are several stories in which he personally committed to transforming Grandma Índio into a symbol of Brazilian Christmas – but, given the lack of documentary evidence, the lines between what was actually the populist politician’s commitment and what became a folk tale are blurred.

“Vargas was committed to nationalizing the country, to creating a national state, to creating a national structure. In this effort he strengthened the image of Tiradentes, for example. And he brought the idea of Grandma Indio, gave his support to spread it,” explains historian and sociologist Wesley Espinosa Santana, professor at the Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie.

“But that didn’t appeal to the population.”

With the outlines of a legend and appearing not in newspapers of the time, but only in articles published decades later on the subject, the most famous of these episodes may have occurred exactly 90 years ago, on Christmas 1931, when the president is said to have organized a Christmas event to introduce Grandpa Índio to children at a stadium in Rio.

According to these reports, the public did not approve of the idea of receiving gifts from a man dressed in a loincloth and with a cockade on his head – the preference fell on the international Santa Claus.

“The fable of Grandfather Índio said that he was the son of an African slave and an Indian woman. He was raised by a white family and, under the influence of his brothers, he stopped being a slave,” explains journalist Marcelo Duarte in his book The Curious Guide – Special edition.

“President Getúlio Vargas even thought about transforming it into a national symbol.”

Historian and sociologist Santana sees parallels between this myth and the Brazilian racial theory of anthropologist Darcy Ribeiro (1922-1997). After all, just like the Brazilian people, Grandpa Índio would also be a mixture of the “three sad races”.

“Vovó Índio was the wise old man, son of a black woman and an Indian, raised by a white woman. The idea of mixing, by bringing a cultural and ethnic syncretism, the three sad Brazilian races: the black because he was enslaved, the Indian because he was exploited and invaded, the white because he was forced to come here”, reflects the professor.

The origin of the myth

Credit, REPRODUCTION

While attempts to bring Grandpa Índio into the national imagination date back to the 1930s, the exact origin of the myth is not known.

What we do know is that its most successful version ended up being published by supporters of integralism, a nationalist movement that became known as a kind of Brazilian fascism.

“There was a great effort on the part of Brazilian nationalist intellectuals, mainly right-wing intellectuals from the 1930s, to create this fable about the Indian grandmother as a counterpoint to Santa Claus,” explains historian Leandro Pereira Gonçalves, professor at the Federal University of Juiz de Fora and author, among others, of “ Fascism in green shirts: from integralism to neointegralism.

It does, however, contextualize the fact that while national symbology was very important to the fundamentalist movement, it was not created by the fundamentalists – rather it was used by their activists.

“The so-called green shirt ended up appropriating this image, this symbolism of aversion to Santa Claus. And this appeared in the fundamentalist newspapers and magazines of the time,” he explains.

Researcher linked to the University of Strasbourg, in France, historian Philippe Arthur dos Reis recalls that the character had previously appeared on the Brazilian musical and artistic scene.

“JB de Carvalho, for example, a Macumbas poet, has already put into perspective the idea of the Indian grandfather as defender of culture. He did it from the point of view of a musician, highlighting black and indigenous culture,” he says.

“I think that this will be done in dialogue with fundamentalism and that then a process of appropriation of ideas will perhaps have taken place.”

Author of the book Brazilian fascismregarding the fundamentalist movement, journalist Pedro Doria believes that the character is the result of the nationalist broth that resonated in the first decades of the 20th century.

This has to do with the modernist movement, whose representatives began the 1920s by reaffirming that it was not necessary to want to be European.

“And begins a search for what it means to be Brazilian. While (writers) Mario (de Andrade) and Oswald (de Andrade) end up taking the path that will become more famous, there is also the path of the green-yellowness of Menotti (Del Picchia) and Cassiano Ricardo, more nationalism. This is the path where Plínio Salgado (the founder of Ação Integralista Brasileira, AIB) finds himself,” contextualizes Doria.

Sociologically, Brazil in the 1930s then reflected on the concepts of Brazilianness. And then there are names like Sérgio Buarque de Holanda (1902-1982) and Gilberto Freyre (1900-1987).

“The idea comes that what is great about Brazil is that we are a mixture of three races,” Doria emphasizes.

In São Paulo, about to celebrate its fourth centenary of founding, the concept of the bandeirante as hero was taking shape.

“But this myth is that of the Caboclo bandeirante, son of a Portuguese man and an indigenous woman, a hero who speaks Tupi, was poor but courageous and explored Brazil,” describes the journalist.

Plínio Salgado (1895-1975) laid the foundations of fundamentalism, mixing this context with an extremist inspiration: Italian fascism.

“But his Brazilian fascism is modernist, it places the caboclo as a founding myth, as the ideal Brazilian man, the one who goes into the woods without fear, who is the face of Brazil,” says Doria.

Grandfather Índio therefore began to be valued in this story.

“For the fundamentalists, Santa Claus was a Yankee influence. Grandfather Índio represented the caboclo, the guy who was in the bush like the Brazilian, essentially Brazilian,” comments Doria.

“It is the result of the search that all fascism has for an idealized vision of what its people are.”

“It was thus consolidated within the AIB and was adopted by Getúlio (Vargas) because it made sense according to this vision,” he adds.

Emissary of Jesus

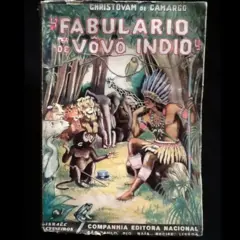

The fable of Grandfather Índio was created by the journalist Christovam de Camargo, who was a friend of Mário de Andrade and, as far as we know, had no connection with the fundamentalists. He published the story in book form in 1932 and then in the newspaper Correio da Manhã, at Christmas 1934.

In Camargo’s story, Vovó Índio was a nature-friendly man who wore colorful feathers and distributed gifts to Brazilians. Expelled from his land by the white man, he died — of “pure grief” — and found himself at the gates of São Pedro.

However, it did not pass the sieve of paradise. Since he had not been baptized by the Church, the heavenly gatekeeper had to explain that he could not enter heaven.

Then Jesus appeared to try to resolve the situation. He said that on his birthday he himself used to go to Brazil to bring treats to well-behaved children and that if Grandpa Índio converted, that’s all, he might very well become the emissary of gifts.

Thus, according to Camargo’s account, Grandfather Índio became the “good old” Brazilian.

Credit, REPRODUCTION

This story also gained prominence because of its religious message.

Gonçalves recalls that after all, “the fundamentalist movement is Christian, its motto is ‘God, Fatherland and Family'”.

“The debate on the symbolism of Christmas really present in Brazilian fundamentalism is not necessarily that of grandmother the Indian, but of the appreciation of the birth of Jesus,” affirms the historian.

At the same time, fundamentalists have always mocked the figure of Santa Claus, considering it incompatible with the Brazilian summer Christmas.

“But despite all the attempts, the image of Grandpa Indio did not work, it did not take root. In the 1930s, the image of Santa Claus was already consolidated in the Western imagination,” believes Gonçalves.

“Vovô Índio was reserved for the aspect of intellectuality, of the utopia of the nationalist activist in search of an alternative to capitalism,” comments the historian.

*This text was originally published on December 23, 2021