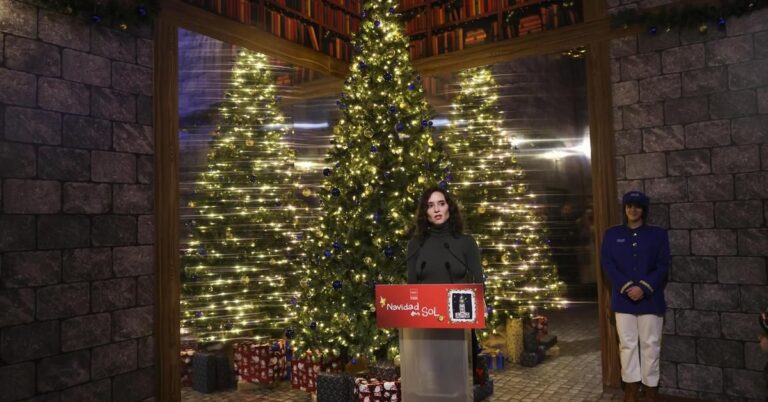

Credit, Getty Images

-

- author, Juan Franci

- To roll, From BBC News World

-

-

Reading time: 7 minutes

“I am the light of the world. Whoever follows me will not walk in darkness, but will have light and life.”

These words of Jesus, contained in the Gospel of John (chapter 8, verse 12), played a crucial role when the authorities of the Roman Empire and the first hierarchs of the Church sought to clarify one of the enigmas of the Bible: when was the founder of Christianity born?

Although the gospels do not mention the date of birth of the one whom today nearly 2.3 billion believers consider to be the son of God, the passage above provided theological support for the decision on the date to be celebrated. Since this decision, Christmas has been celebrated on December 25.

The date was not chosen at random, but with the firm intention that it coincide with one of the great moments of the Roman calendar: the feast of the Unconquered Sun.

A cult of the Orient

The Sol Invicto festival, whose official name was Nativitas Solis Invicti or “birth of the Unconquered Sun”, was a celebration dedicated to a solar deity celebrated on December 25.

But who was this god? “We don’t know it very well. It wasn’t very common in the catalog of Roman deities,” Spanish historian and biblical scholar Javier Alonso told the BBC.

In turn, the professor of ancient history Santiago Castellanos, from the University of León, in Spain, adds that this deity “was not one of the most present in Roman political practice, at least it was not at the level of Jupiter and Mars, which had a greater implantation in terms of temples and statues.”

As with Christianity, the cult of this god arrived in Rome from the East, notably from present-day Syria. It was brought by the hands of Emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus, better known today as Elagabalus.

The sovereign, who reigned only four years (218-222 AD), removed Jupiter from the top of the Roman pantheon. In his place he placed El-Gabal, a solar deity whom he worshiped and of whom he was high priest in his homeland, Emesa (present-day the Syrian city of Homs).

To facilitate religious change, the god was renamed with the Latin name Deus Sol Invictus.

“Sol took over the whole solar cult which, in the Greco-Roman world, was associated with the figure of Helios and also with his iconography,” added Castellanos.

Credit, Getty Images

solar deity

Invictus was not the first solar deity worshiped by the Romans, but he was the one who marked the calendar. Indeed, in 312 AD—nearly a decade after his conversion to Christianity—Emperor Constantine decreed the seventh day of the week to be the most important day of the week. Solis dies (day of the Sun), what we today call Sunday.

The emperor ordered that this day be a day of rest for “the magistrates and the inhabitants of the cities, where all the workshops will be closed”.

Castellanos says that imperial support was fundamental to the consolidation of this cult, but the belief had already begun to become popular throughout the empire.

In addition to Sunday, Sol Invicto also held a festival that was part of the busy Roman calendar of year-end festivals, which included the Brumalies and Saturnalia.

The first, celebrated in November, were the winter solstice festivals and were established by Romulus in honor of Bacchus. Saturnalia was dedicated to Saturn, god of agriculture, and lasted seven days starting on December 17. They were very popular among the Romans.

“At that time there was a certain inversion of the established order, for example, slaves were more important than they normally were,” Castellanos explains.

“Large banquets were organized. Gifts were exchanged and houses were decorated with garlands and candles. These Saturnalia which took place in December have liturgical and festive foundations which Christianity then incorporated into its own liturgy,” he adds.

During the celebrations, excessive drinking and sexual relations were common, according to accounts of the time, so it seemed like a cross between what we know today as Christmas and Carnival.

Alonso explains that the Romans decided to establish the Festival of the Unconquered Sun almost immediately after Saturnalia for an astronomical reason: the winter solstice.

“The winter solstice is the day of the year when there is less sunlight. However, from then on the days start to get longer and in the ancient world it was thought to be the time when the Sun regenerated and was reborn,” he says.

Credit, Getty Images

And why these holidays?

When Emperor Theodosius declared Christianity to be the official religion of the Roman Empire, in 392 AD, a desire arose among civil and ecclesiastical authorities to clarify certain unresolved doubts in the gospels, in order to facilitate the adoption of the new faith by the Romans. And among them was the date of Christ’s birth.

Birth was a taboo subject for Jews and early Christians.

“The law does not allow us to celebrate the birth of our children,” explained the 1st century Judeo-Roman historian Flavius Josephus in one of his writings.

On the other hand, for the Romans, celebrating birthdays was, in some cases, a duty. For example, since 45 BC, they annually performed public sacrifices in honor of the birth of Julius Caesar.

“When Christianity began to be a powerful religion, linked to emperors, it became necessary to establish a precise date for the birth of its founder,” explains Castellanos.

“They needed to anchor a date in the calendar for liturgical reasons,” explains the expert.

Alonso states that the Feast of the Unconquered Sun was ideal to mark the birth of Jesus because of its importance to the Romans.

“Pope Julius I decided that the birth of Jesus would take place on the Feast of the Sun, during the winter solstice, because he believed that the sun conquered darkness,” Alonso explains.

“In ancient societies, celebrations were linked to the agrarian calendar and everything revolved around sowing and harvest time. In the past, festivals took place at harvest time and, over time, saints were added. But originally, everything was linked to agriculture,” he says.

In search of religious justification

The choice of the feast of the Sun was justified by certain passages from the Gospels, such as the one which says that the Messiah will come “from above to visit us like the rising sun, illuminating those who live in darkness” (Luke 1, 78).

Or the one who says that “a light has shined to those who live in the shadow of death” (Matthew 4:16).

And of course, there is the story of John, who claims that Jesus is presented as “the light of the world.”

But Pope Julius I’s decision, which was approved nearly a century later by Emperor Justinian, not only put Christmas on the calendar, but helped do the same for other celebrations.

“Other important feasts of the liturgical calendar would have been fixed accordingly: the Annunciation (9 months earlier), the Nativity of Saint John the Baptist (6 months earlier), the Circumcision of Jesus (eight days later) and the Presentation in the Temple (40 days later),” adds Professor Luis Sánchez Navarro, of San Dámaso University (Spain).

For experts, this choice should not come as a surprise, as it has happened before.

“When the Romans conquered other regions of the world, they took over the cults and traditions of those regions, but of course they reinterpreted, modified or shaped them,” Castellanos explains.

Alonso, in turn, asserts that when one culture imposed itself on another, it appropriated its rites and sacred places.

“That’s why when we dig under a church in some places in Europe, for example, we find a mosque, further away a Roman temple, and further away a ceremonial center from another earlier city.”

Another theory

Luis Sánchez Navarro explains that there is another theory about the date of December 25.

He admits that there is a historical basis for understanding that Christmas was placed on a date that coincides with the pagan festival of the Unconquered Sun, but he asserts that there is also evidence indicating that December 25 may in fact have been the date of Jesus’ birth.

“There is an ancient tradition, linked to the church of Jerusalem, which places the birth of Jesus around December 25.

In the year 204 (many years before the establishment of the Feast of the Unconquered Sun), Hippolytus of Rome, in his commentary on the book of the prophet Daniel, clearly stated that Jesus was born on that day. “Some scholars question the passage as a later placement, but others maintain its authenticity,” he explains.

Sánchez also cites the discovery in Israel of a calendar from an ancient Christian sect that would reinforce the theory that December 25 was the day of the birth of the historical and religious Jesus.

*This text was originally published in December 2023