Last March, Yolanda Gálvez Sánchez, a 54-year-old resident of Arahal (Seville), went to have a screening mammogram in a mobile unit (a caravan) of a private clinic subcontracted by the Andalusian Health Service (SAS), which had parked in her town. For her, it was already a routine.

However, the usual response they gave her – “if there is anything we will call you in ten or fifteen days” – did not meet this deadline and when they contacted her, five months had passed since the test and the diagnosis was positive for cancer which needed to be confirmed by further scans. Today, with two chemotherapy sessions already and the feeling of having lost six months to start her treatment, she accuses the Ministry of Health of “treating women like animals, not like people”.

Yolanda’s case predates the outbreak of the breast cancer screening scandal, which put the government of Juan Manuel Moreno on the ropes, precisely because of a number of late mammogram diagnoses that were not informed to those affected.

The screening crisis, which caused the resignation of the Minister of Health and half a dozen senior officials in her department, was limited to a single hospital – Virgen del Rocío – where the Council counted more than 90% of the women concerned, 2,317 according to the figure proposed by the Council. The Andalusian Executive has not yet specified the exact origin of the decision nor the criteria for quantifying the total number of people concerned – questioned by the Amama association, which discovered the case – nor the period covered by the internal investigation (from what date did the SAS begin to examine the results of the mammograms which were not communicated to the women?)

From the start of the crisis until the end of November, the Ministry of Health telephoned the 2,317 women selected to schedule a new contrast mammogram, because during the first examination, a doubtful or inconclusive result had been obtained of which they were not informed.

Yolanda’s case opens a new scenario which questions this perimeter of the screening crisis. She was not called, she is not one of the 2,317 women affected by a doubtful diagnosis: her mammogram detected a malignant lesion, but she was only informed of it five months later, when the cancer had already developed.

Change of treatment in 2020

As El Pespunte progressed, Yolanda’s story goes back to 2010. It was in that year that she was diagnosed with “bilateral nodules in the left breast”, which changed in size, but without presenting danger, in addition to presenting numerous cystic areas inside and bilateral cysts.

Yolanda keeps dozens of documents in a box at home. Medical reports from the gynecology department of Virgen de Valme Hospital detailed her life in stages from 2010 to 2020, with mammograms and ultrasounds every time she presented for consultation. But in 2020, they transferred her case to a private clinic that performs mammograms organized by the SAS in mobile trailers throughout Andalusia, and the SAS left her without an ultrasound. He visited this mobile unit twice, the last time last March.

To compensate for the lack of dual treatment, she goes to a private gynecologist, whom she consults once a year. But everything happened recently without an unexpected twist. When she had her mammogram in March, they sent her away with the usual “if we see anything, we’ll let you know in ten or fifteen days.” The days passed and no one warned her about anything, so she imagined that everything was fine, already thinking about the visit in 2027, but it wasn’t like that. At the end of August, he received a letter informing him “not only that the test was positive, but that he already had an appointment two weeks later to begin cancer surveillance.”

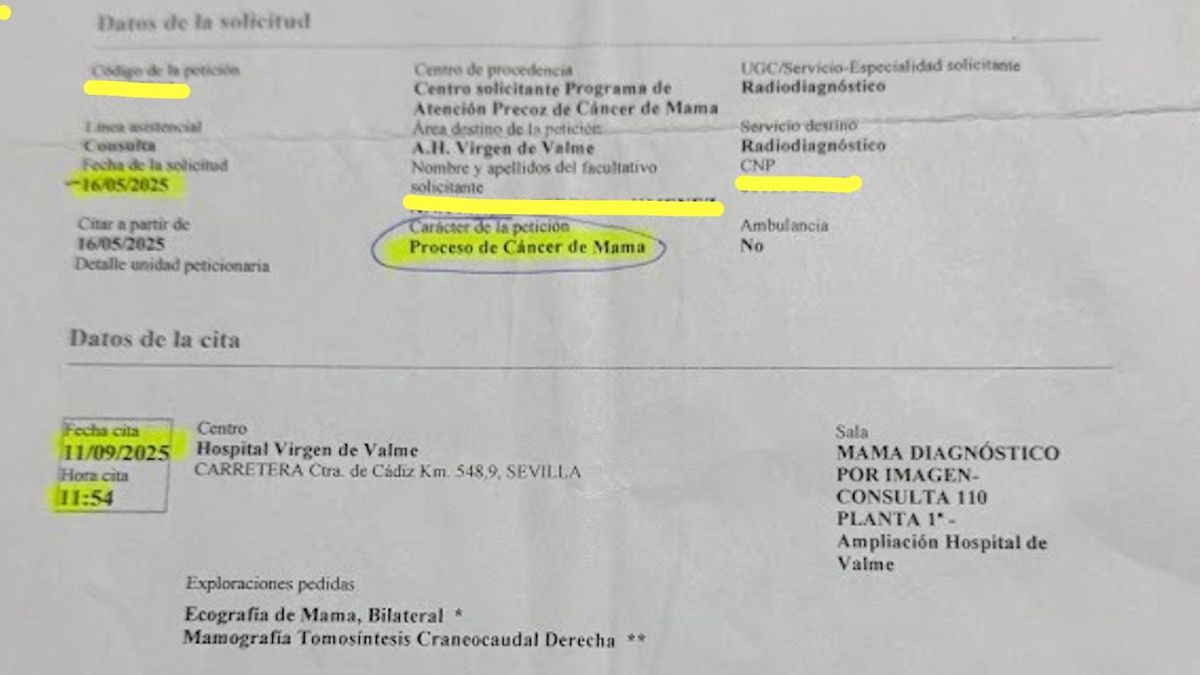

The letter informed the woman concerned that a doctor had examined her mammogram on the previous May 16, two months after carrying out the test, and had summoned her at 11:54 a.m. on the following September 11 to attend the consultation at the Virgen de Valme Hospital to undergo a “bilateral breast ultrasound” and a “right crancocaudal tomosynthesis mammogram”.

Not only was Yolanda’s test on hold for two months until a doctor saw her, but the “urgent” appointment requested by the doctor was given for September 11, four months later, and the woman was not informed until two weeks before.

The tests confirmed that Yolanda suffers from breast cancer which affects one breast, of which she showed no symptoms, “and that she could have had a better prognosis” if she had been informed of the diagnosis without delay: “if I had been told at the beginning of April that I have cancer, I would have gained six months and I would not go through this ordeal”, she said.

Two chemotherapy sessions after a pilgrimage of tests

The person concerned also emphasizes that she has not received any communication of the positive decision, “only the letter from the end of August with the medical appointment”, and that to date she has already received two chemotherapy sessions before the operation to remove the tumor, which she hopes will be reduced so that the intervention is as less harmful as possible.

Since she was scheduled, she has undergone mammograms, ultrasound scans, a lymph node biopsy of her breast and arm, a contrast-enhanced CT scan, a PET-CT scan – a diagnostic imaging technique that combines positron emission tomography (PET) – and an axial computed tomography (CAT) scan to obtain metabolic and anatomical information about the body).

This Thursday, December 4, he had his third session, and he assures that they cause him “all the negative consequences that they can have”, so he hopes that the operation already scheduled will serve “to put an end to this torture”.

“Let the Council think”

Yolanda worked as a housekeeper, but explains that she had to quit her job and asks the Andalusian government to think about the fact that “they are playing with women’s lives” with these screening errors, and she hopes that her case will help those responsible for this delay in diagnosis to realize that “these are not animals, but people.”

To avoid fighting alone, she contacted the Association of Women with Breast Cancer (Amama): “they asked me for all the documentation and I signed the use of my data”, and she plans to organize a rally in Arahal “because she knows that at least two other women, residents of this city, were also victims of this screening failure”. Their goal is now to make them “aware of the need to talk about it so that it doesn’t happen again.”