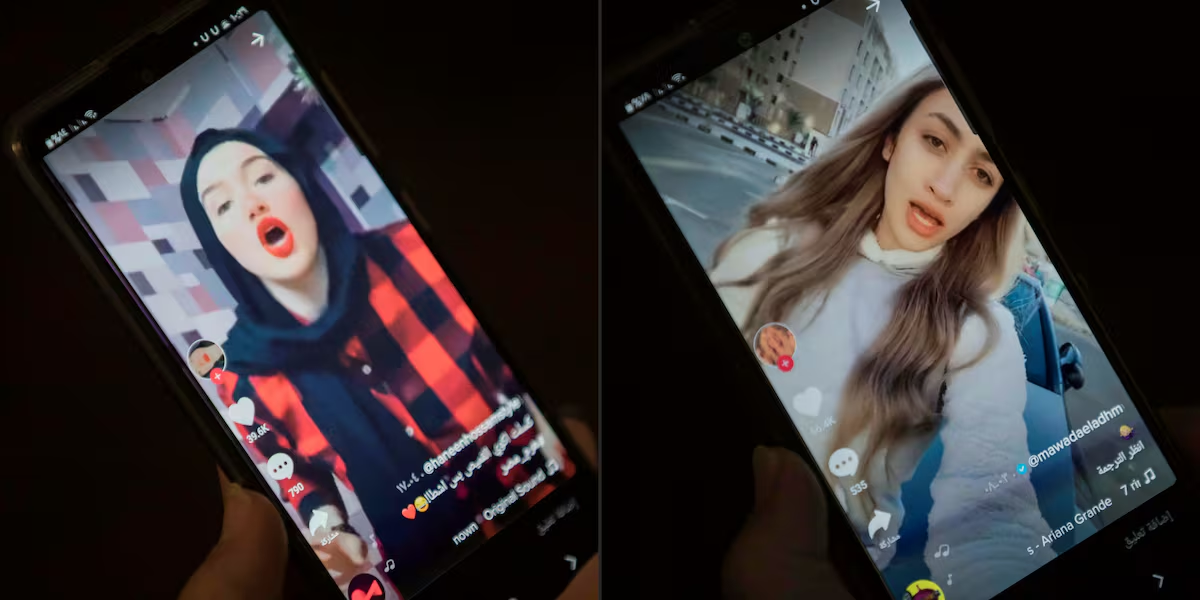

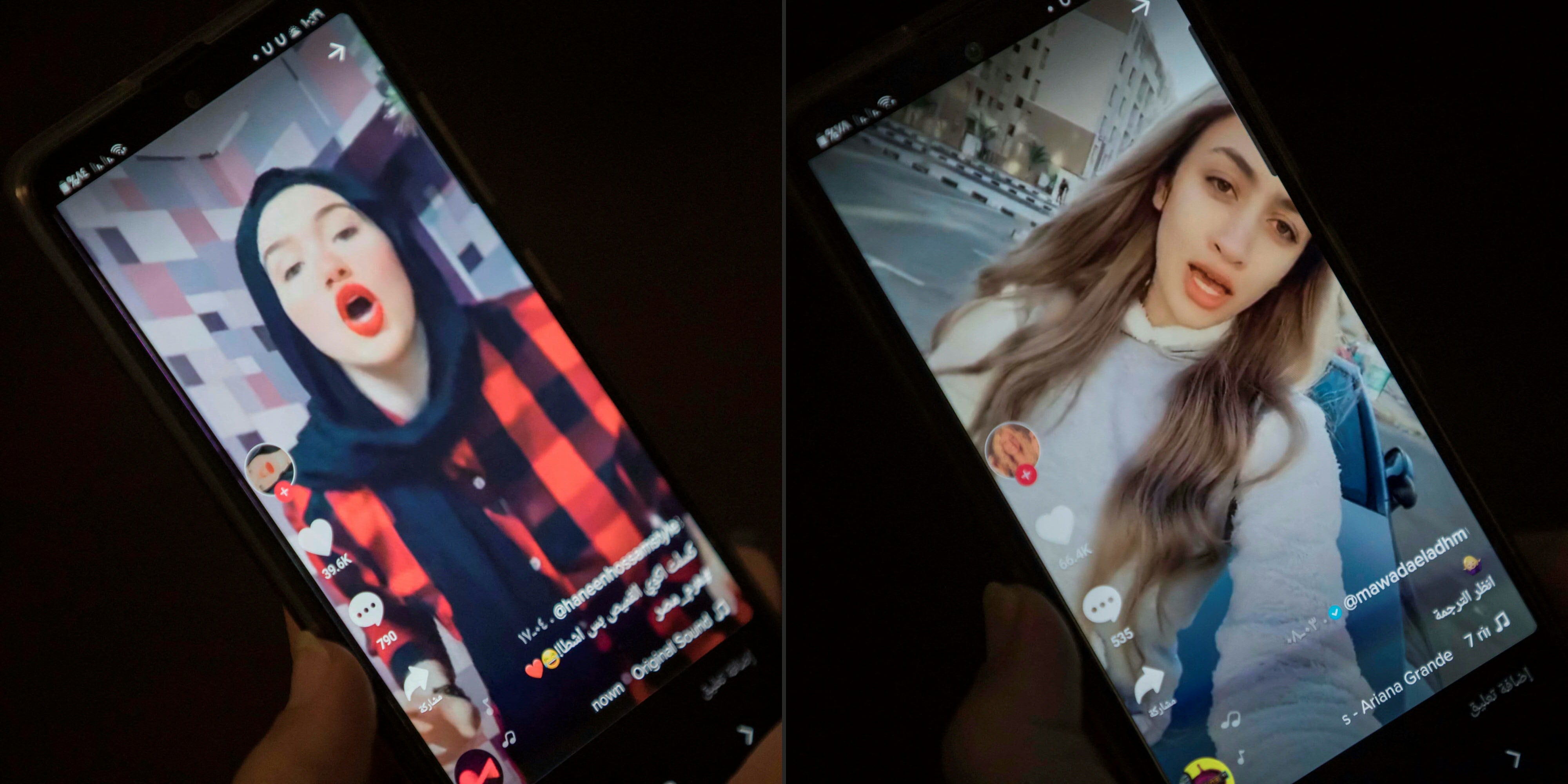

The posts, in dozens of cases, follow a virtually identical pattern: the Egyptian Interior Ministry shares on its official Facebook account a photo of the detained people with blurred faces, wearing household clothes and, in front of them, money and other confiscated items, such as phones and photographic equipment. In a few minutes, the event exploded and spread through different media. The crime? Often, having used a digital application to advertise or share content deemed “immoral”.

In recent months, such arrests have accelerated in Egypt, where authorities are using charges that human rights groups consider vague, such as violating “family values” and “public morality,” to arrest content creators for non-political videos uploaded to networks they describe as “indecent.” The first cases date back to 2020. Since then, at least 327 people have been arrested in 252 trials, according to a recent report by the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights (EIPR). But in recent months, these arrests have accelerated. Since August, at least 167 people have been arrested in 134 court cases, according to EIPR, which equates to more than one per day over the past five months. The majority (107) were again women, in what EIPR sees as an attempt to control their personal choices in dress and image to conform to a more conservative and idealized ideal of working-class women.

One of the most publicized cases was that of a tiktoker known under the fictional name Suzy El Ordoneya, who began posting content from her daily life in 2021 while she was a high school student. Over the past three years, after becoming very popular, the young woman has been investigated in seven different cases, accused of violating family values, insulting religion, money laundering, spreading false news and even inciting public disorder and belonging to a terrorist group, according to her lawyers.

Some men have themselves been arrested for posting content that human rights groups say does not conform to the archetype of acceptable masculinity due to issues such as their dancing. On August 12, police also arrested a young woman for posting “indecent” videos and claiming she was “a man pretending to be a woman,” according to Human Rights Watch (HRW). EIPR has also documented investigations of gay men based on private and personal content taken from dating apps.

Also among the profiles arrested since August are five artists from tattoo studios, generally considered prohibited by Islam, as well as a comedian who hosts a talk show in which he speaks in language that is common and common to many Egyptians, but which some may consider vulgar, according to the EIPR.

“Prosecutors are very conservative in Egypt and are generally from the upper middle class and upper class,” says Mohamed Lotfy, director of the Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms (ECRF), who believes that many “see society as something to be disciplined.” “Who are these young women who show themselves like this, who wear provocative clothes and speak with foul language?” This is an affront, and in the name of society we will take them to court so that no one else does the same,” said the Egyptian human rights defender.

Social control through sanctions

“The main objective is to exercise social control through sanctions, trials and prison,” interprets Lobna Darwish, director of the women’s and gender rights program at EIPR. “At the class level, it’s about creating restrictions and limits on who and how can advance socially and economically, particularly people from poor or lower-middle-class backgrounds,” he adds, and “the second issue is how gender roles should be understood.”

In most cases, as human rights groups have documented, detainees face criminal charges for violating “any of the family principles or values of Egyptian society,” as stated in an article of the 2018 cybercrime law, which does not detail what is meant by family principles and values in Egyptian society. From these initial charges, it is common for the accused to be exposed to an additional crime of money laundering due to the fact that the original economic activity is considered illegal.

Initially, the targets of these arrests were young women, but among all the cases documented by EIPR over the past five years, the number of men and women accused was almost identical, and the majority were concentrated in Cairo and Alexandria. What they generally have in common is that they are content creators from popular backgrounds who make social media posts that do not conform to what the state and much of Egyptian society considers a priori correct and acceptable.

“At first it was limited to women being more conservative in the way they dressed and behaved on camera,” says Darwish. “(But) now it is also about the way they speak, the way they express their femininity or masculinity, who can dance, what types of dances are allowed, even the type of voice used,” adds the researcher.

Morale check request

Furthermore, when these types of arrests began to occur in 2020, the prosecution explicitly encouraged citizens to monitor public morality and report content they deem unacceptable. Groups like EIPR point out that this petition has contributed to a growing number of lawyers devoting themselves to filing complaints against content creators, without fear of being accused of defamation, and taking the opportunity to promote their firms.

For Darwish, the campaign of arrests and prosecutions also aims to control a new path of upward mobility at a time when traditional forms, such as education and employment, no longer offer, to a large extent, any type of mobility. The defense of the family, underlines the researcher, also occurs after a decade of liberal policies of the Egyptian government and a rapid withdrawal of the State in its social and economic intervention.

“The state is withdrawing from the social responsibilities it had in health, food, education,” Darwish says, and the right to organization and association, although included in the Constitution, “is restricted, so that there are no social institutions other than the family.” “The family becomes the only space where we can obtain a safety net,” explains the researcher. “Without that, people are left to their own devices,” he concludes.