Fear of violence has led 72% of Brazilians to change in one way or another the routine to which they were accustomed, shows the latest Datafolha survey on the impacts of violence on public security – or lack thereof – on the population.

The survey interviewed in person 2,002 people aged 16 or older in 113 municipalities across the country between December 2 and 4. The margin of error for general sampling is plus or minus two percentage points, at the 95% confidence level.

The most visible change concerns cell phones: 56% of Brazilians say they have stopped using their devices on the street in the last 12 months.

These are attitudes that also extend to traffic and the domestic environment.

The survey shows, for example, that 36% of Brazilians say they have changed their route to work or their place of study for fear of violence.

31% started taking off their rings, chains and other accessories when going out on the street, and a smaller percentage, 27%, said they stopped doing something pleasant.

Concretely, believes lawyer Cecilia Mello, retired judge of the TRF-3 (Federal Regional Court of the 3rd Region) and specialized in criminal law, the result shows that insecurity is increasingly close to the population.

“Before, there was the false idea of controlled violence. This assumption that ‘it won’t happen to me’, that ‘it happens to so-and-so because he’s not paying attention’. But the problem has gotten so bad that it has shown that no one is safe from violence.”

According to Datafolha, 26% of Brazilians have stopped leaving their homes for fear of violence.

Women are the most affected both in the general profile and in the thematic samples.

The change in routine due to fear of violence affects 76% of them. In the case of men, 68%. When dividing by gender, the margin of error is plus or minus three percentage points.

They are the majority among those who do not use a cell phone in the street (62% compared to 49% of men) and represent the majority of those who have stopped doing something pleasant: 31% compared to 22%.

For Mello, the difference represents “a very serious social distortion that we are experiencing”: the Brazilian Public Security Yearbook 2025 showed an increase in cases of violence against women, which include feminicides, attempted feminicides and protection measures, among other crimes.

As shown Leafthe share of the population who considers security to be the country’s biggest problem has further increased and reached 16% of the population. As a result, the subject comes just behind health, which accounts for 20%.

The change in habits is more significant in metropolitan regions, where 80% of residents say they have taken action out of fear of violence. Inland, the rate was 66%.

The main difference lies in the use of cell phones in the street, a habit abandoned by 68% of residents of metropolises compared to 47% of residents of rural towns.

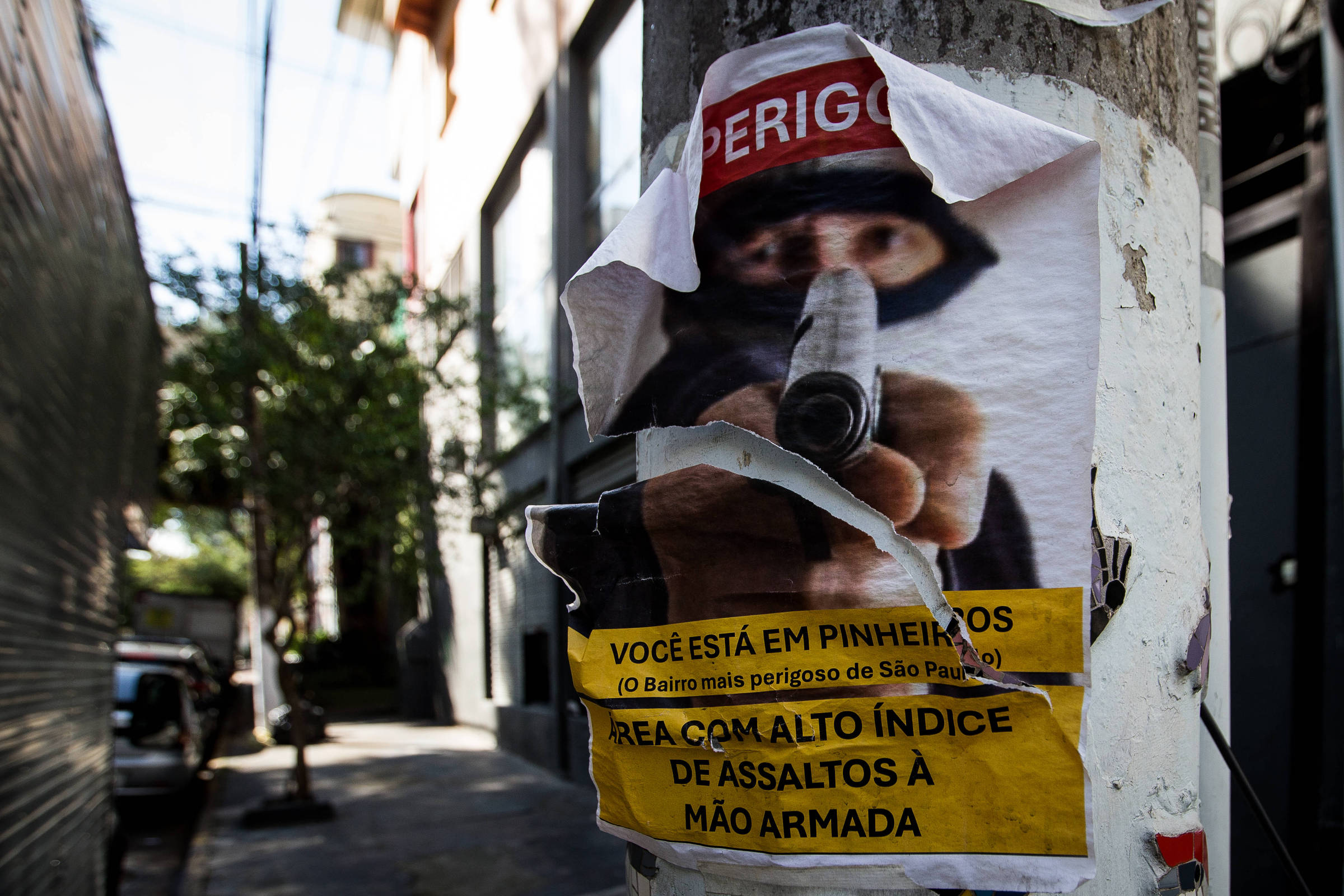

This is data that accompanies other statistics. The city of São Paulo, for example, saw an increase in homicides (2.8%) and robberies (4.6%) during the first ten months of 2025 (the most recent data available), compared to the same period the previous year. This move goes against what has been recorded in the state, which saw a decline in both indicators: a 2.6% reduction in homicides and a 0.1% reduction in robberies.

The fear of violence affects all age groups. It reaches more than 65% in all groups, and is highest among people aged 60 and over (77%).

This is also seen among those who voted for Lula (70%) and Bolsonaro (76%) in 2022. In terms of the electorate, the margin of error is three points for the PT member and four for the former president.

For sociologist Cláudio Beato, coordinator of the Center for Studies on Crime and Public Security at UFMG (Federal University of Minas Gerais), the figures also represent an indicator of quality of life.

“If you don’t have the peace of mind to go out on the street, it means we live in a very bad environment,” he says.

According to him, this results in a chain effect that affects both the social and economic domain.

“People are consuming more and more in closed and protected places,” he says. Then come the aspects related to housing.

“We’re seeing the proliferation of larger and larger gated communities, which offer all services indoors. That means people don’t mix, they don’t coexist with different classes. And you start to have a biased view of those outside of those bubbles.”

The fear, Beato says, is not necessarily about factions or organized crime, although both affect the popular imagination around violence.

“It’s a behavior shaped by what happens in daily life, on the street. Like when a person is stopped at a red light and sees someone stealing the vehicle in front of them or the pedestrian’s cell phone.”