Over the past two weeks, almost daily, a series of barbaric crimes have shocked the country: in all of these crimes, the victims were women – raped and killed because they were women. In Florianópolis, a 21-year-old woman was raped and strangled on her way to a swimming lesson. In Jaborandi, Bahia, another woman, aged 27, was taken out of the shower and shot dead by her ex-boyfriend. In the northern zone of Rio, an official shot dead a teacher and a psychologist from the Federal Center for Technological Education (Cefet) Celso Suckow da Fonseca, in Maracanã. In São Paulo, a woman was killed by her ex-husband in the pastry shop where she worked, and a young woman was run over and, still trapped in the vehicle, dragged into the street. Her legs were amputated and hospitalized in serious condition. The suspect in the crime, according to the victim’s family, had a brief relationship with her.

- Barbarian crime: Army soldier victim of feminicide found burned in barracks in Federal District

- “Unscrupulous men”: Deolane promises to help woman with leg amputation after being run over and dragged by ex

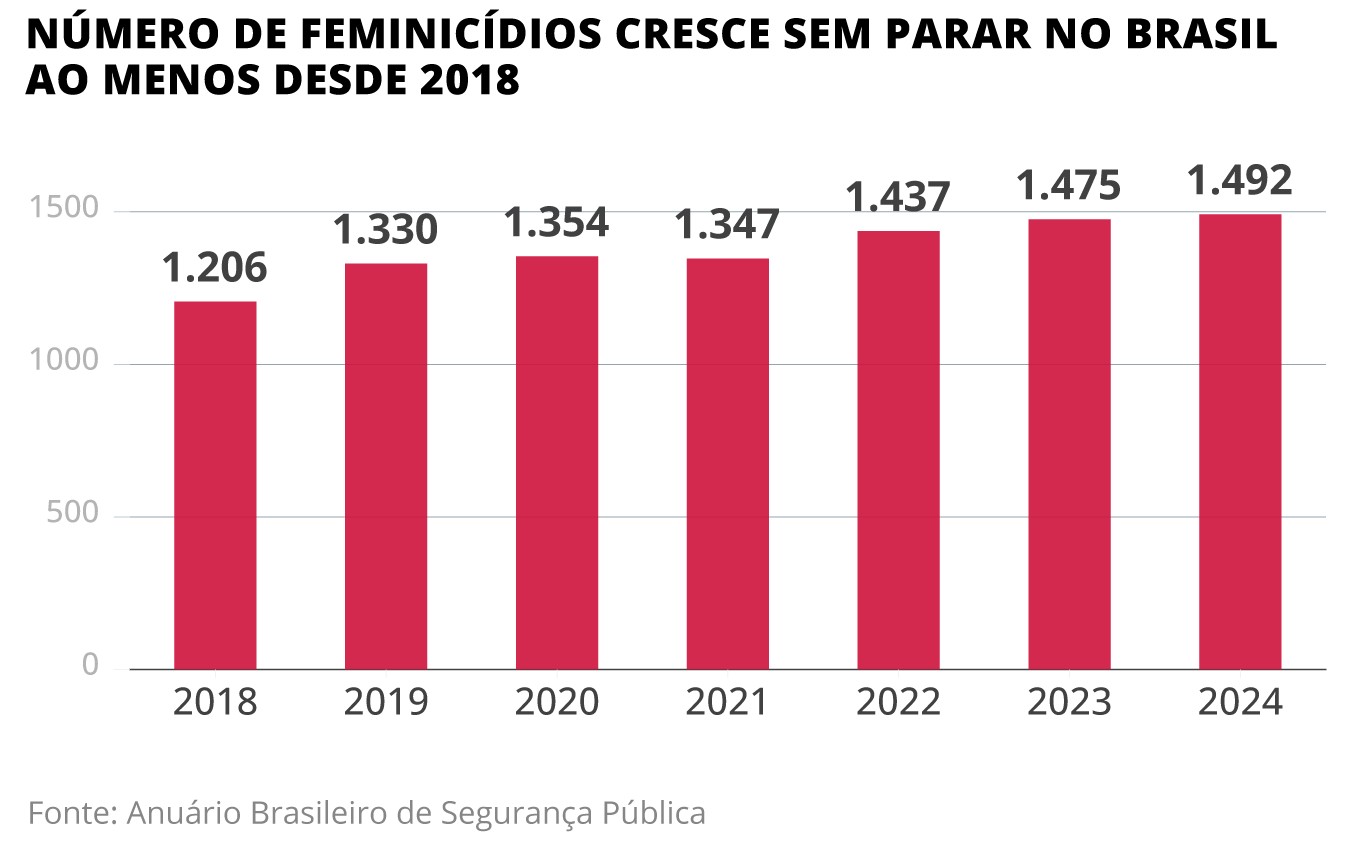

In 2024, Brazil broke the record for femicide since 2015, when the crime was classified by the law sanctioned by former President Dilma Rousseff: 1,492 cases. In the capital São Paulo alone, according to data collected by Globonews, there have been 53 feminicides this year alone, the highest number in the historical series. In the state of São Paulo, feminicides have increased by 10% since January, the Sou da Paz Institute reported. And the number of murders of women on public roads has almost doubled since last year: a jump from 33 to 48 cases, if we compare the first ten months of 2024 and 2025.

/i.s3.glbimg.com/v1/AUTH_da025474c0c44edd99332dddb09cabe8/internal_photos/bs/2025/9/R/FLZVDlSFypxkBECk7m1A/bra-07-12-feminicidos-brasil.png)

Violence against women is also breaking records on the Internet. In Rio, reports of criminal and virtual harassment have increased by more than 5,000%, from 55 to 2,834 over the past decade, as documented in the recently released Mulher Dossier.

The recent explosion in the number of crimes is therefore not an exception, but proof that the country is experiencing an epidemic of violence against women, the result of centuries of social brutality and misogynistic culture.

— It is undeniable that social networks have radicalized hatred of women and femicide in Brazil, transforming this violence into very lucrative content. But, if the change in magnitude of the scope of this information is new in contemporary times, hatred and violence against women are constitutive of the history of Brazil. This means remembering what has been and is still erased from our history: the economic, political and cultural development of Brazil was born from the dehumanization and objectification of women through colonial exploitation, forced labor, control, surveillance and all kinds of violence against their bodies and minds — lists historian Patrícia Valim, professor at the Federal University of Bahia (UFBA). — Women who resisted violence and shaped our society have been attacked, mutilated and killed.

Patrícia is the author of texts that rescue the stories of women who were killed because they were women and dared to take control of their own lives. The content recounts the violence to which they were subjected, details the arguments mobilized to defend the murderers (such as “self-defense of honor” and “momentary madness”) and questions how Brazilian society in the 19th and 20th centuries created the stories of these women – some of them transformed into miraculous saints or ghosts who still wander aimlessly today.

This all seems unfortunately current. The texts also denounce the persistence of legal and social vices which, even today, condemn women to death. For Patrícia, remembering these stories means humanizing these women and showing that their existence is not limited to being victims of femicide.

— We must confront this “morgue” of archives to save invisible lives in a way that challenges the reproduction of femicide and the erasure of these histories. Levante Mulheres Vivas will occupy the streets throughout the country to commemorate these women and put an end to this violence — says the historian, referring to the demonstrations taking place today throughout Brazil to defend the lives of women.

Read one of the historian’s texts below.

“Legitimate defense of honor”

Salvador, April 20, 1847. Night was falling when João Estanislau da Silva Lisboa, aged 27, broke into the house of Júlia Clara Fetal, his ex-fiancée. He shot the 20-year-old girl in the jugular, tried to kill her mother, Frenchwoman Julie Fetal, and seriously injured the hand of judge Manoel Vieira Tosta, a neighbor who was dining there, and managed to call the police to arrest the killer in the act.

The crime was covered by newspapers across the country. Conservative politicians aligned themselves with the popular outcry demanding justice and exemplary punishment for the murderer. To defend the accused, liberal politicians proposed a softer sentence and spoke for the first time of “self-defense of honor”: João Estanislau would be an honest and hardworking man who, because of a “senile passion”, momentarily lost his reason in the act of the crime.

Created during the trial of João Estanislau, the provision for deprivation of reason was included in the Republican Code of 1890. “Those who find themselves in a state of total deprivation of sense and intelligence during the act of committing the crime are not criminals,” states Article 27, § 4, which continued to allow acquittal and sentence reduction even after being removed from the Penal Code of 1940. The thesis of “legitimate defense of honor” had a long life in the trials for feminicides in Brazil.

The grandson of a slave trader, João Estanislau was born in Calcutta, India, and raised in Salvador by his mother, the Englishwoman Mary Ann. Financial decline did not prevent them from hobnobbing with the Salvadoran elite. The boy, however, became the first in the family to have to work to earn a living. He taught geography at the Liceu Provincial and taught English. It was as a teacher that he arrived at Júlia, who at the time had received the typical education of a white, rich girl: she played the piano, sewed, drew, spoke French and seemed destined to marry a boy from the same social group. João Estanislau fell in love and asked her to get engaged after the first lesson.

News of a possible marriage between the bride’s fortune and the groom’s traditional surname excited Salvador. But Julia was not in love. She was beautiful and full of life; He was depressed, moody and fighting all over town. The final break occurred when the young woman met Luiz Antônio Pereira Franco, a law student from Recife who was spending his vacations in the neighboring house of the Fetal family. The two men exchanged letters with his mother’s consent. Expelled from classes, refusing to accept the end of his engagement and feeling publicly betrayed, João Estanislau swore revenge. Late one April afternoon, he made good on his threat.

While his trial was scheduled, João Estanislau claimed to have health problems and admitted himself to Santa Casa de Misericórdia to dispel the rumor that he was planning to run away. On September 29, 1847, two-thirds of the jury freed the defendant from the death penalty and sentenced him to 12 years in prison. The defense succeeded in getting the court to recognize a man’s right to avenge his honor. The innovation of the trial was to interpret honor as an inviolable property and to introduce the concept of “momentary madness”, capable of depersonalizing a man with a “good past”, whose crime would be the result of an occasional act of despair and jealousy.

João Estanislau continued to teach English to the children of the Bahian elite, who took them to the prison for lessons. Upon his release from prison, he took charge of the most prestigious educational establishment in Bahia, the Colégio São José. In 1876, he published the book “Atlas Elementar”, adopted by provincial schools and still considered today as a reference work. Today, she gives her name to a street in Baixa dos Sapateiros, in Salvador.

The remains of Júlia Clara Fetal rest in the church of Graça, in the capital of Bahia. Her story was told in verse and prose, and more than once her desire to be free and marry the man she loved was used to justify her murder. In “ABC of Castro Alves”, Jorge Amado describes her as “treacherous as the current, she loved to see the eyes of men on her face and to see the hearts of everyone she met attached to her smile”.

In 2023, 176 years after Júlia’s assassination, the thesis of “legitimate defense of honor” was unanimously considered unconstitutional by the Federal Court. But it still remains to be eradicated from Brazilian society.