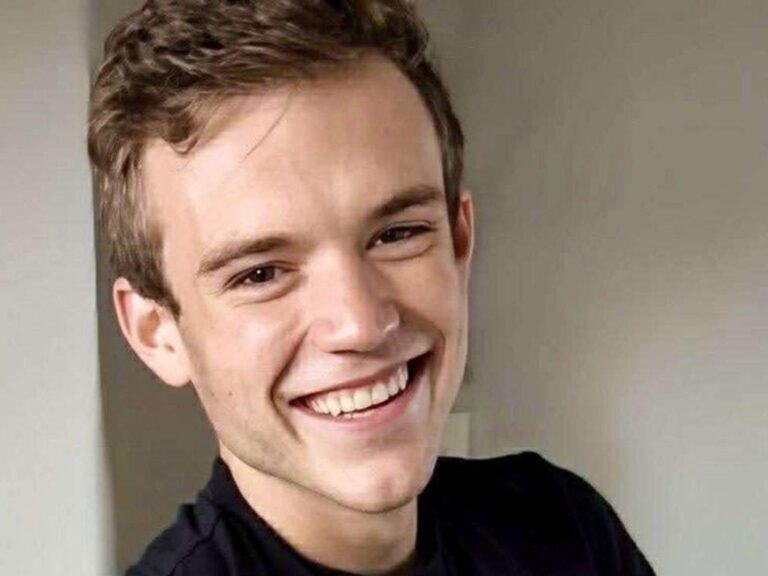

Credit, Personal archives/Pol Deportes

-

- author, Alexandra Martins

- To roll, BBC News World

The challenges of football go far beyond what happens on the pitch. And the story of Cliver Huamán Sánchez, 16 years old, known as “Pol Deportes”, demonstrates this very well.

A viral video has prompted hundreds of thousands of people around the world to follow the Peruvian teenager on social media.

Cliver traveled more than 16 hours by bus with his brother Kenny and his father Simeón.

He left his native province, Andahuaylas, in the south of Peru, to realize a dream: to narrate the final of the Copa Libertadores de América, played on 29/11 at the Monumental Stadium in Lima, the Peruvian capital, when Flamengo became champion by beating Palmeiras 1-0.

The young man was unable to enter the stadium, but he did not give up. He climbed a hill overlooking the Monumental and, from there, his live report on TikTok, filmed by his brother, sent social networks crazy.

Today, he realizes another dream. The support of many people and especially “Uncle Santi” – as he calls Peru-based Spanish TV presenter Santi Lesmes – brought Cliver and his brother to Madrid, Spain. And this time, he didn’t stay off the field.

In Real Madrid’s legendary Santiago Bernabéu stadium, Cliver reported on Wednesday (10/12) the Spanish club’s match against Manchester City in the Champions League.

The match ended with a 2-1 victory for the English and Pol Deportes’ TikTok account reached the two million follower mark.

Overflowing with emotion, the young man told BBC News Mundo, the BBC’s Spanish-language service, his story full of passion, perseverance and marked by the love of his family and an entire community.

Credit, Personal archives/Pol Deportes

Overcome fear

“It all started in my town, when I was three,” Cliver told the BBC.

“My father took me to the radio so he could speak, tell stories. And, when I was seven or eight years old, I worked on the farm with my uncles, who had me narrate in Quechua (a family of indigenous languages of the Andes which today has around 10 million speakers).”

The boy started narrating football matches at the age of 11, but he encountered a powerful ghost: fear. This is because a few people made fun of his stories.

“So like any 11-year-old, I stopped and stopped for a year and a half. I kind of had trauma after they made fun of me at the stadium and I was afraid it would happen again.”

“When my brother recorded me, I didn’t want him to record my face and I told him, ‘film the wall and I’ll talk’.”

But little by little, the boy gained confidence and was encouraged to show his face.

“The first time I narrated live, I was as hard as a statue,” he says.

At age 13, he started reporting for a local media outlet called Pasión Deportiva Apurímac. It was his brother Kenny who convinced him to create his own platforms, under the name Pol Deportes.

The nickname “Pol” came about because, when he was younger, Cliver wanted to become a police officer.

His journey was also marked by economic difficulties, but there was something he never lacked: the unconditional support of his family.

Credit, Personal archives/Pol Deportes

Sacrifices and incentives

“My brother influenced all of this, my brother who has always been with me,” Cliver told the BBC.

His brother Kenny, now 19, went to work in Lima to earn money and fulfill his younger brother’s dream.

“My brother had to work to be able to pay for the Internet to make our videos. He had to stop studying.”

Managing to tell the story of football with confidence “did not happen overnight”, he guarantees, but “a very long process, three to four years”.

Kenny returned to Andahuaylas from Lima and became his younger brother’s cameraman. They made a video of a local match that was viewed six million times. Many people in Andahuaylas began to cheer them on.

“They supported us and told us, ‘Pol, you must continue’; ‘Pol, you are the future of Peruvian journalism’.”

“And I began to say that there are many people who trust me. I believe that I must serve them and my brother, my father and my mother who have always been with me.”

Cliver often remembers the words his mother Lida said in Quechua.

“You have to chase your dreams. You have to pursue them. We will be here to support you.”

“And that’s where my mentality changed and I finally decided to pursue this world of journalism and storytelling.”

The feat of the Libertadores

When Cliver and Kenny traveled to Lima to broadcast the Copa Libertadores final, the city council paid for the bus ticket.

Before heading to the capital, as a giant screen showed a local football match in the city’s central square, Cliver was excited to take the microphone and ask for help to realize his dream of narrating the Libertadores final.

“I took the microphone and said: ‘Look, my name is Pol Deportes. I’m going to the Copa Libertadores final. I don’t know if you could support me by liking the videos.’ And I told a little.”

“People were emotional, they hugged me and said ‘you have to go, you have to put Andahuaylas high’. And I had all that in mind, I couldn’t disappoint them all.”

“A few companies, with their little grain of sand, have also trusted us.”

Credit, Kindness Pol Deporte

Upon his arrival in Lima, Cliver managed to record interviews with supporters of both Brazilian clubs. But the police did not allow him to access the Monumental Stadium.

“I was sad,” he remembers. “And I told my brother that we would go back to Andahuaylas this afternoon. But he told me ‘you won’t come back disappointed’.”

While they were thinking about what to do, they went to the aviary of a provincial neighbor who lived in Lima, who suggested the boys go up the hill.

“He told us ‘I once recorded a video on the hill carrying chicken and it’s been viewed a million times. And I think we can go’.”

“On the hill, I set up my tripod, gathered my courage, with my father as commentator and my brother filming.”

In the second half of the year, more than 10,000 people followed the live broadcast on TikTok. The recording that followed quickly surpassed one million views.

All this with a microphone he received as a gift from his uncle, attached to a homemade cube assembled by Cliver himself.

“I made this little cube out of necessity because no one sold it in Andahuaylas. I made it with cardboard and a dishwashing sponge and I always have it with me.”

Credit, Personal archives/Pol Deportes

“Super incredible” treatments in Madrid

His experience arriving in Spain was “super amazing,” Cliver says.

“First of all, I thank God, I thank all the people who support me so that I can reach Madrid,” he exclaims.

“The affection of the people here in Spain was truly incredible. We also did a live broadcast in Peru and there were many fellow Peruvians. I am proud to be Peruvian and happy to be here.”

While preparing for the Champions League match, Cliver offered his predictions for the World Cup.

“I think for the 2026 World Cup the favorites are Spain and Portugal.”

When he returns to Peru, the young man wants to finish his secondary education and study communication.

“There are universities that want to support me and the government wants to give me a scholarship,” he says.

Whatever his background and thanks, in large part, to the values he received from his parents, adolescents have one very clear point.

“One last question,” offers the BBC News Mundo report. “How do you think you can achieve your dream of becoming a journalist?”

“With faith, perseverance, work and humility,” Cliver responds.

Cliver Huamán Sánchez was interviewed by Agustina Latourrette, from the BBC News Mundo video team.