Today is the first different day. Yesterday was the last one with you. I won’t see you again until death dies -If he does that. For five minutes, I only found you in my memory, when crossing that half-open door where … They live the days when there is no harm. I say goodbye to you without flowers or letters: just the noise of a keyboard that refuses to accept your last sentence. This song is your Garcia de Paredes office. Then everything was slow and I was immortal. Today it feels like two voices as I write what changed five minutes ago.

You, who always despised emotion, left everything soft and fragile. Not by surprise, but through that pain that lets what disappear when it is still necessary. Above all, in your, The eight grandchildren Today they lose the innocence of sadness, without being able to do anything to have you for a little longer. Determinism is also a respite; A clumsy consolation for the irreparable. It happens with literature: When I read you, I knew who you were; By writing to you I can say goodbye. The truths that hurt are those found in literature. That’s why it matters.

You taught me not to complain, that honesty is not a virtue, it’s a way of life, and that sometimes silence is the only elegant gesture when everything around you is a mess. Cancer – that time-biting monster – forces you to light every cigarette as if it were your last. I think about how much my mother loved you, Pilar, and the way she supported you while you gave up everything else. And in Uncle Javier, the alchemist, loyal, meticulous, and formidable. Two of them extended your life. You say you’ve suffered so much these months that disinfectant would taste like relief. I answer that if beef isn’t served in heaven, you’d rather stay there, leaning against the bar counter where the last drink is always first.

I think you would have liked that: that the world didn’t stop, that there was no unnecessary drama, that life went on in a clumsy, wonderful way without asking for permission.

I think about Your laugh It happens everywhere. It advances noiselessly, like an August morning in Ruiloba, when one listens to its breathing and understands, for a moment, that life is a tightrope between two silences. And I find myself talking to you inside, like children talk before they know they are losing too. This conversation is a mandate at your table at the Estrada Club, even if the chair is empty and the afternoon remains without a companion.

I step out into the street and Madrid continues to do its thing, with that tired indifference of cities that have seen it all. And I think you would have liked that: that the world didn’t stop, that there was no unnecessary drama, that life went on in a clumsy, wonderful way without asking for permission. Soon praise will arrive, profiles, General masks of Ussía that I was on: Invincible prose. Inexhaustible laughter. Golden Decade of Radio; madridista; Mr. Sutuanzhou. dude; Kavya; Rowan. Incorruptible to me you were that and my father too. And I write because it’s the only way to walk with you without making noise. Between word after word, I find crumbs of your shadow, and that is enough – at least today – so that my soul does not melt between my fingers.

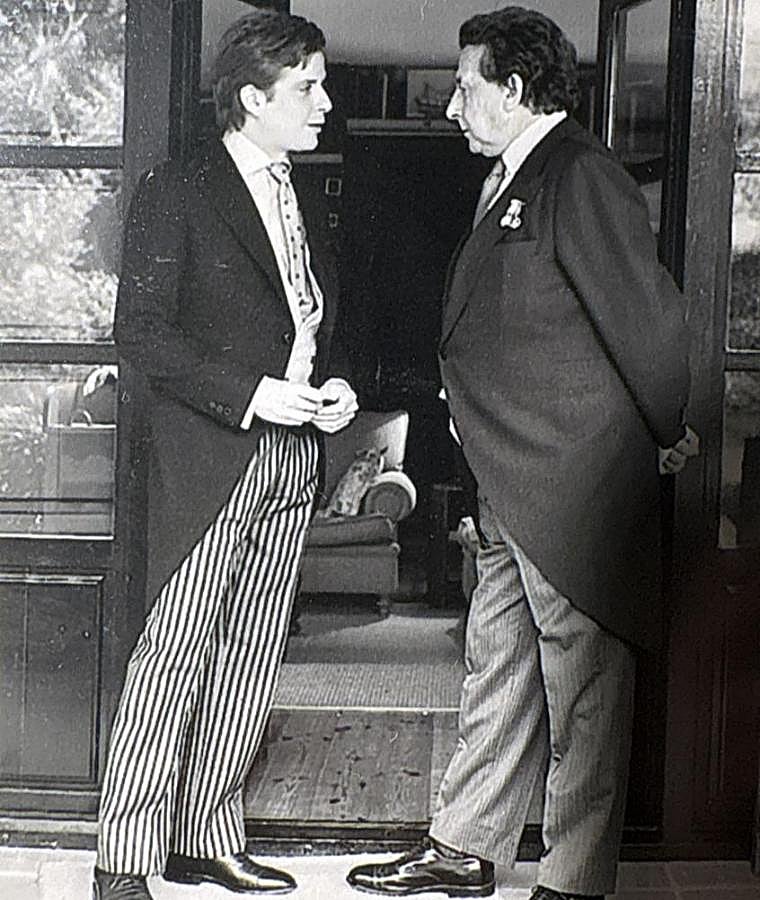

Today I feel like a foreigner in my own home, among these walls full of frames and pictures of Muñoz Sica, Mingotti, and you. Still everyone. Everyone is quiet

Madrid in black and white

“Death is not the end” is written in Morphine of Faith which I cannot find anywhere. Of course it is. It’s always been that way. Life is a tragedy: they all end equally badly. Writing is my reward and it was the best gift to you. Today I feel like a foreigner in my own home, among these walls full of frames and pictures of Muñoz Sica, Mingotti, and you. Still everyone. Everyone is quiet. I was Beau Brummel with the Bel y Cía jacket. I don’t know which part of you was more Puerto or La Concha. You get lost in Manuel del Palacio and always come back to Woodhouse, while touring La Garaleira between Cádiz and Seville. In La Montana you decided to stay, even though you never stopped walking through Madrid in black and white, glass after glass, hair after hair. Always at the heart of the conversation. With laughter ahead. Seductive, brave, brilliant. Without a fucking wrinkle in his shirt. In Norteña, your ink ran dry, so you wrote until your last breath. Without knowing – or wanting – to do anything else.

Father and son walk in a snapshot from the family archive

Vuksa, one of your poets, left behind him the “sorrow of disappearance.” I have heard it from you so many times that now it breaks the silence with your resigned voice: “And I believe that I cannot, in my selfishness, take the sun or the sky into my palm; That I should walk alone into the abyss, that the moon would shine just as brightly, and that I would see it no more from my box. I can’t ask you to come back. I won’t invent consolation either. She’s gone, and that’s a phrase that doesn’t allow for adjectives. But as I write, there’s something about you that insists on staying: a story, a way of looking, a trace of a laugh you can’t hide. And so I continue. Because what hurts today indicates that It continues to make noise as it is no longer there.

And in this confusion I find a way not to lose you completely.

Alfonso J. Ossia