At the age of 12, Jaime Manquillo left his family home in La Argentina, municipality of Huila, tired of the domestic violence generated by his father. Attracted by the possibility of a better life, he agreed to accompany one of his older brothers (he had 10 children) and a maternal uncle to El Caguán, in Caquetá, where raspachines were earning very well thanks to the coca boom. He arrived in the early 1980s, and in his new job he received triple what he earned doing other jobs in his town.

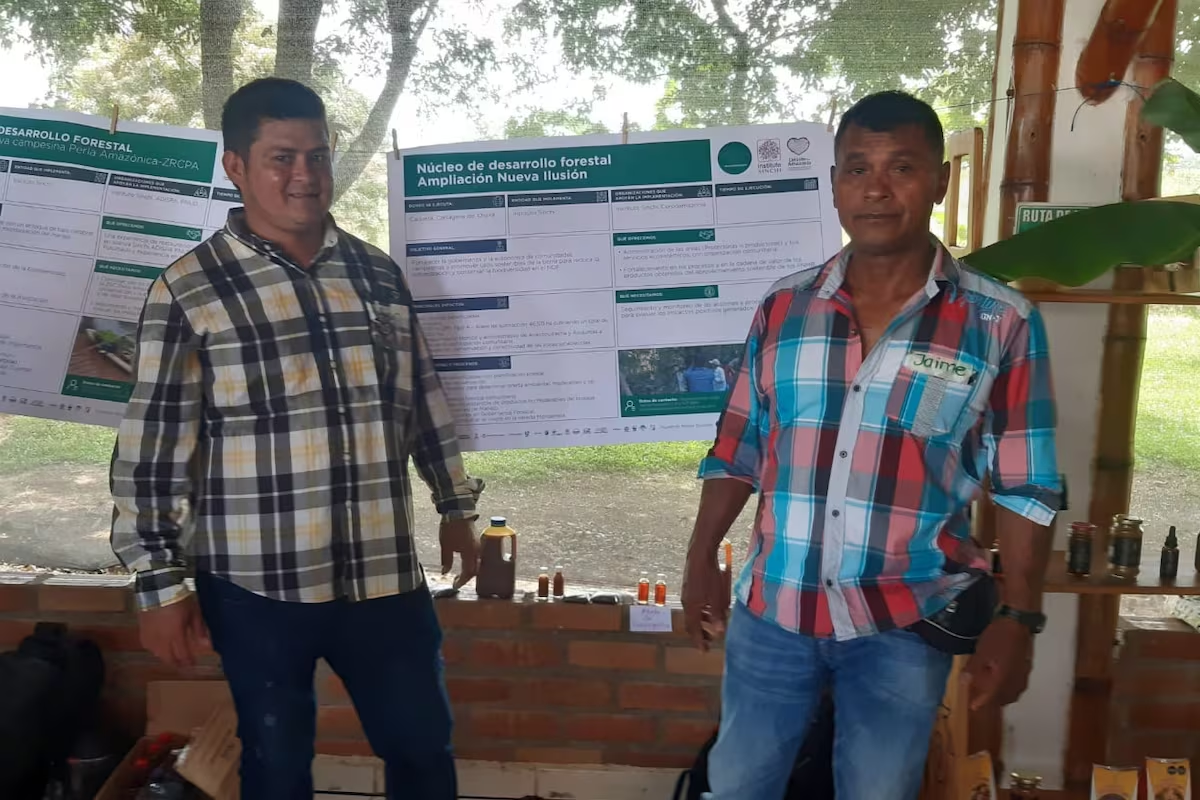

Today he is 57 years old, he lives in the village of Santo Domingo, he has three children, he recently separated from his wife and is president of Acaiconucacha (Comprehensive Peasant Community Association Núcleo Number 1 of Cartagena del Chairá). Created in 2018 with 250 families from 15 villages to seek as a community how to solve the hunger problems that tormented them, it now has 750 families.

Upon his arrival in Caguán, he settled in the village of Caño Negro, an area dominated by FARC guerrillas. During these years, a leadership capacity was awakened in him, as he had made his debut as class president at the Huilense school where he attended his first years. He also acknowledges that, despite his father’s distance, he learned to lead from him and from interviews with Professor Alexander Achuri. He wanted to fight for the rights of peasants, affected and stigmatized because they found themselves in the middle of the crossfire between the subversives and the army. He served as president of the Community Action Board for eight years and also managed the football team.

When he left his post, his replacement was assassinated, a fact that marked him and for which he raised his voice in protest against the armed actors. Faced with the threat of possible reprisals, he moved to Santo Domingo in 2000, where another of his brothers welcomed him. Coca crops began to give way to livestock. Manquillo experienced the gradual deterioration of the forest.

Then officials from the Conservation and Sustainability Foundation arrived and told them about a community reforestation project, aimed at preventing further destruction and finding ways to use the jungle, but sustainably. One solution was to create productive corridors, mixing timber, non-timber trees and pan-port crops. Manquillo received seeds, plants, kits solar and wires.

His house, made of wood, zinc roofs and a plank floor, is located in the middle of 220 hectares of his land, of which he devotes only 50 to pasture for the few livestock he has. The association’s meetings always take place in their room, where they discuss strategies for respecting and recovering biodiversity and the environment.

The arrival of programs from the Amazon Institute for Scientific Research (Sinchi) has also helped raise awareness: “75% of residents believe that we must take care of the forest, we already understand that extensive livestock farming is making the jungle disappear. With the association, which is non-profit, we take care of reforestation, create biological corridors and restore water sources. We are looking for ways to survive, because the economy here is complex.”

Learning to overcome situations to preserve life is what all the inhabitants of the region do. Despite this, he considers it a privilege to live in this jungle: “There are difficult times and even more, being a social leader, you have to know how to measure everything very well, to be attentive to what is said and what is done. I hope that subsequent leaders will not experience the same situations; not much, but it helps mitigate “The ideal is that one day we receive what is fair for this conservation work.”

The results of the association’s work are already visible, such as the improvement of the slopes of certain rivers and the recovery of land made arid by livestock farming and deforestation. Having a dignified life, with respect for the earth, is the objective. Manquillo’s leadership reflects the commitment and resilience of rural communities who, from the heart of the Amazon, demonstrate that peace and sustainability are built by caring for the land and strengthening the social fabric.

For 45 years living in the jungle, Manquillo’s greatest pleasure is standing at the door of his house, breathing and enjoying the greenery: “The forest is everything, life, health, I can’t describe it. We were deforesters, but today we know that we must be careful, and justify ourselves to new generations. We cannot leave children and grandchildren a desert, a future full of heat, overflowing rivers, avalanches. leave them something good.