“Grandmothers should be forever” is a phrase that many of us would like to get tattooed or tattooed on ourselves – literally or figuratively – because their impact on our lives is indeed eternal, because of their influence, because of the many questions they answered us, because of what they took care of us, what we discovered with them, the times they picked us up, the afternoons we spent in the park with them, the snacks that they prepared for us and the occasional fights that they engaged in with us. Always right.

They are eternal because they have the capacity to transcend us and accompany us even when life forces us to exchange roles, from children to caregivers, the transition from innocence to the most complete awareness that they need us, even when they do not remember us, until the last of their precious days.

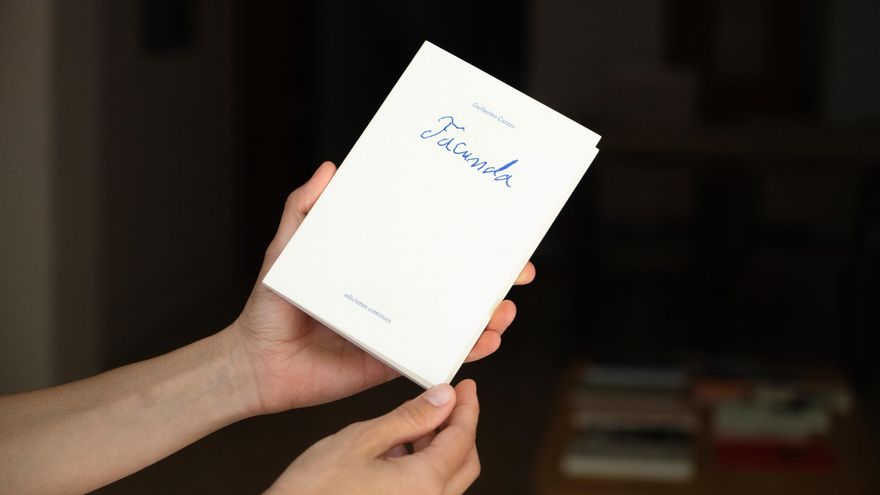

“It’s a photo book that my grandson made of me”, is the handwritten sentence that opens easy (comisura editions), the photo book in which Guillermo Carazo reconstructed the story of his grandmother, and with her that of his family, marked by her Alzheimer’s disease, which in turn embodies the memory of an entire country. The visual communicator and journalist has constructed a unique volume, delicate and small in form, but immense in intimacy, which allows you to immerse yourself little by little in the life of a woman, while being your own. And that of so many families, of so many family ties, of so many injustices perpetrated in the homes of those who raised us, of those we love most, of whom we must largely be as we are, with whom we remember crying for the first time, as happened to this visual communicator and journalist.

Guillermo Carazo signs a work of art, certainly, but also an exercise in sincerity which shocks because it speaks to many. He puts an image and a text there about the desire to have eyes which, because of Alzheimer’s disease, have ceased to look the same, to orient themselves in the same way, to recognize each other and to recognize each other in the same way. And not just to pay homage to his Facunda, but also to talk about what hurts, how uncomfortable it is, as common as it is. It is said – with certainty – that inheritances break up families, but before these, worries break them up. This is why this book has such a universal component, without losing an iota of beauty, it speaks and shines from the inside to stay inside, in what marks us, in what we know, in the realities with which we live, in the pains that we identify, in the desires that we would like not to understand, in the realities that we live.

“Grandmothers tell you things that they don’t tell your mother,” admits Guillermo Carazo, returning to the origins of this personal project. His grandmother was very present in his upbringing, which led him, in fact, to document his life “always”. It was during the pandemic, at a more pronounced stage of her grandmother’s Alzheimer’s disease, that she became more aware of the “story” she wanted to record: “I started taking more photos of her, recording her, continuing to create archives, sharing what she was telling me.

The idea at the time wasn’t that all of this material would eventually take the form of a book, but it ended up being one. A treasure of “domestic archaeology”, as he defines it, which begins with a photograph of his grandmother which repeats itself to go from a blurry image to a clear image, counterbalanced by the memories that his grandmother finds increasingly difficult to live with. easy It is a memory exercise with which Carazo found a way to counteract a disease that works in precisely the opposite way.

Before inheritance, care

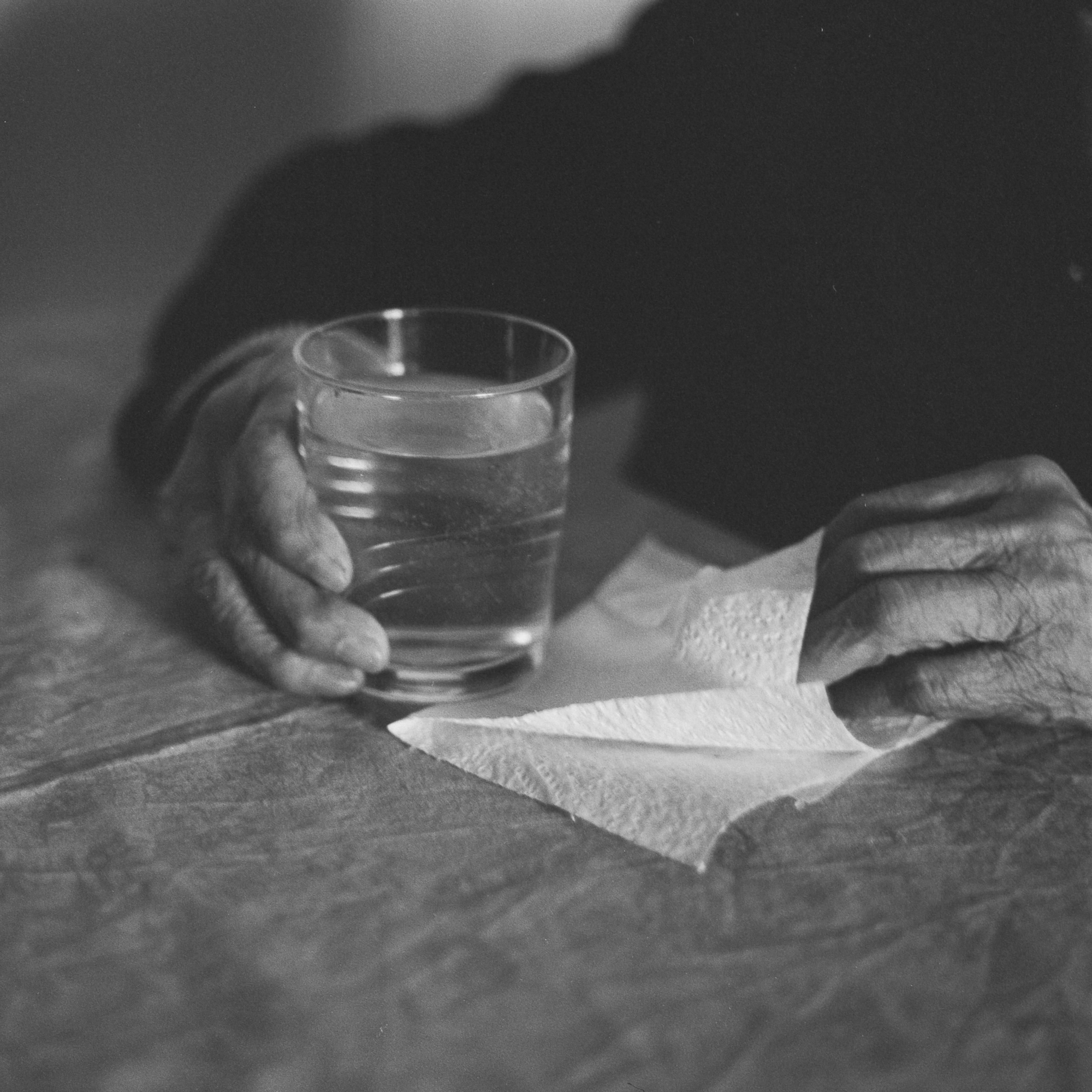

Care is one of the great protagonists of the book, because in addition to documenting the life of his grandmother, this journalist opened the doors of her house, which could be that of many, to also tell what the environment of this woman is like. More specifically, her mother and her aunt, who were the ones who took care of Facunda the most. These are the great “gifts” of a book that also addresses absences, the most notable being those of her uncles, men, who ignored their mother’s care.

“I decided not to ask them anything, because what was I going to tell them, why didn’t you spend more time with your grandmother? It wasn’t like that, it wasn’t constructive or real. I wanted to tell our story, and it was going to reflect things that happened to me, like being more detached from the family, because I had a lot of taboos with certain uncles,” he shares. Carazo let the testimony of the geriatrician from Facunda speak, in one of her reports, in which she recounts a visit during which the grandmother appeared with one of her children.

“He acknowledges that he does not take care of his mother’s appointments and paperwork. He also does not provide up-to-date medications and does not know what he is taking, if there have been any changes. It is not helpful for his mother with cognitive impairment to know the current medications. She has a caregiver who takes care of her, but who does not come to the consultation because the son does not want to, even if the mother insists that he come,” the doctor wrote, and the visual communicator captures it in his book.

Who takes care of our elders

Carazo tells the story of a family which is at the same time that of so many others, because of whom this care falls, outside of congenital circles. In Facunda’s case, there were fifteen caregivers hired irregularly. With the exception of one, they came from Latin America, with an average age of thirty-five. In the eleven years they used them, “one of them spent almost three years. After that, only one continued for more than a year. None had any specific training in working with people with dementia.” Carazo explains that this limitation was marked by the economic resources of her family and was at the origin of discussions between Facunda’s children “in which there was never a consensus or a particularly favorable situation for the employee.”

All have assumed what he defines as a situation of “neo-slavery”, which he regrets because it is an “underground economy”. And, beyond his working conditions, it was not the best context for Facunda and his illness. “At first it was a problem because she had a stranger every few months in her home, her safe zone, and she was forced to share her privacy and care with them. A problem that caused various situations in which she reacted with verbal abuse against the caregiver and against us, her family.”

Carazo says that during those first months, Facunda expressed “insecurity about her financial situation” and that she thought they were “stealing her money from the bank and things around the house.” One night resulted in an episode in which they ended up letting go of two of the people who ended up caring for their grandmother, because one of them “thought it was appropriate for her to take the antipsychotic medication one of the nights she came into her room.” Something they discovered thanks to a camera they had placed in the house to find out how Facunda was doing.

The last potato omelette

The photo book is raw and very direct, certainly, but also luminous. And it is precisely for this reason that it functions as a tribute, moving, sincere and beautiful. A beauty that is in the texts, but especially in the photographs. Especially the one he took without knowing that he had just witnessed the last time he saw Facunda cooking a potato omelette. It is also moving because of its continued reflection, among other topics on the knowledge of silences and efforts within families, of the margins for improvement, on questions that will ultimately concern us all, because the day will come when it will be time to reverse roles with our elders, starting with our grandparents, and especially continuing with our parents.

“I hope the next generation won’t be so wrong. I’m an only child and I’ve been talking to my mom and dad for a long time about what they want to do. They always tell me they don’t want to be a burden. And I know that’s a decision that can’t be made now, but the logic is that at some point you end up becoming dependent,” he says. It is true that in the case of Facunda, to this dependence is added an illness as cruel as Alzheimer’s disease, which made her grandmother “a shell of what she was”, and that this meant that in her more than ten years of discomfort: “There are few that involve this type of mourning in life”.