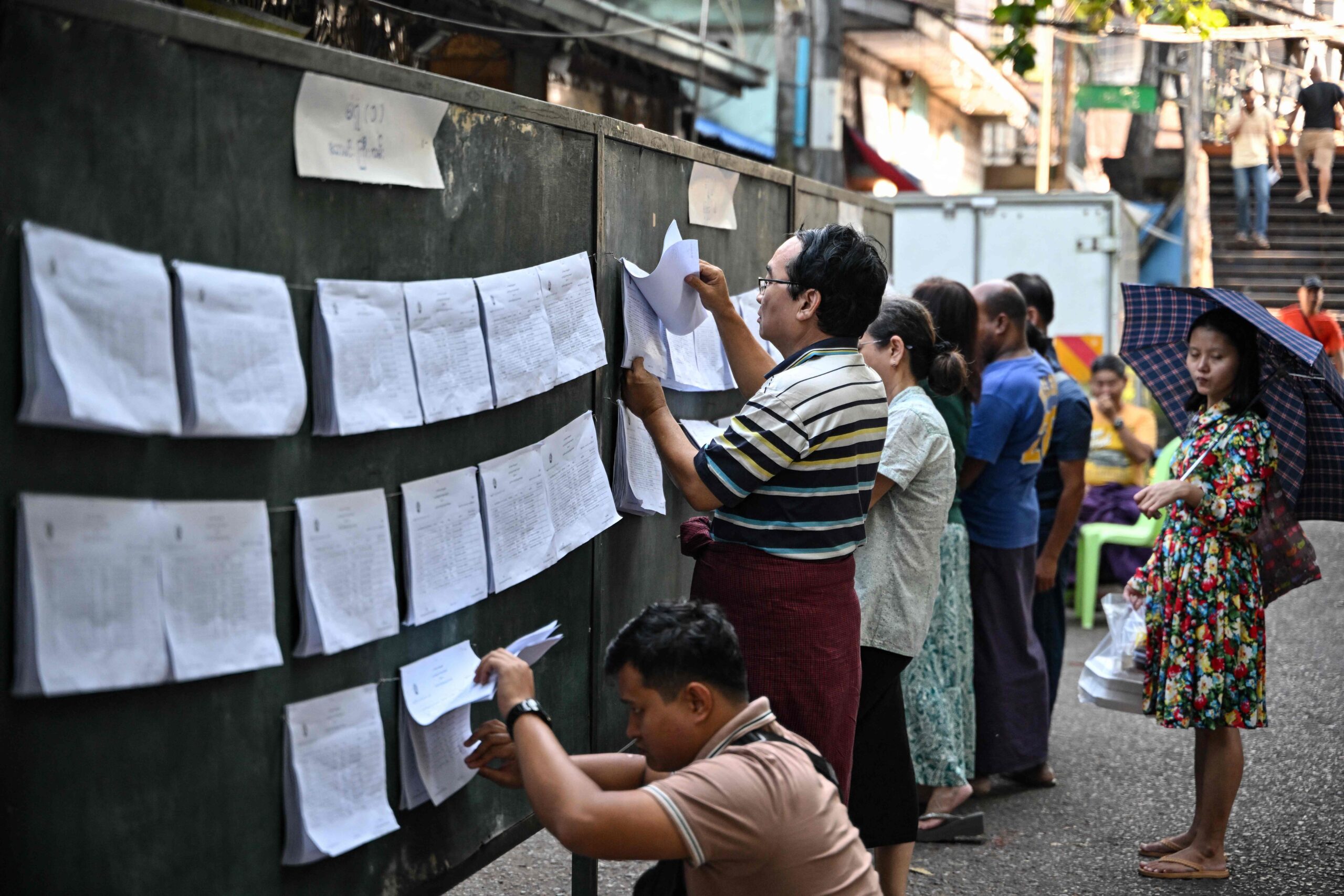

Myanmar’s military junta is presiding over elections that begin this Sunday, heralding the vote as a return to democratic normalcy five years after leading a coup that sparked a civil war. The vote was widely seen as a sham aimed at overhauling the military regime, which annulled the results of the last 2020 elections, alleging massive electoral fraud.

- Also read: Kast wins Chile’s presidential elections and faces Congress without a defined majority

- Outlook 2026: Weak diplomacy, elections and growing Israeli occupation hamper progress on Palestinian issue

The pro-military Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) is by far the largest participant, providing more than a fifth of all candidates, according to the Asian Network for Free Elections (ANFREL). Former democratic leader Aung San Suu Kyi and her party, the popular National League for Democracy, which won a landslide victory in the last election, will not attend.

Following the 2021 coup, Suu Kyi was arrested on charges that rights groups said were politically motivated. According to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (AAPP), a human rights group, around 22,000 political prisoners are languishing in the military junta’s prisons.

/i.s3.glbimg.com/v1/AUTH_da025474c0c44edd99332dddb09cabe8/internal_photos/bs/2025/3/G/7dZFxySPuEvUuyHRGBgQ/113389024-a-member-of-myanmars-union-election-commission-uec-prepares-a-voting-station-a-day-before.jpg)

The National League for Democracy and most parties that participated in the 2020 elections have been dissolved. ANFREL specifies that the organizations which won 90% of the seats on this occasion will not be present in the ballot this Sunday. The vote takes place in three phases, spread over a month, using new electronic voting machines which do not allow candidates to be recorded in writing or invalid votes.

Who can and who cannot vote?

Myanmar’s civil war has caused the military to lose large swaths of the country to rebel forces – a mix of pro-democracy guerrillas and ethnic minority armies who have long resisted the central government – and voting will not take place in areas they control. A census conducted by the military last year acknowledged that it was unable to collect data on about 19 million of the country’s more than 50 million people, citing “security restrictions.”

Amid the conflict, authorities canceled votes for 65 of the lower house’s 330 elective seats, almost a fifth of the total. More than a million stateless Rohingya refugees, who fled a military crackdown that began in 2017 and now live in exile in Bangladesh, will also have no voice.

How is the winner decided?

Seats in parliament will be allocated according to a combined system of simple majority and proportional representation, which ANFREL says largely favors the major parties. The criteria for registering as a national party capable of running for seats in various areas was tightened, according to the Asian Election Observation Organization, and only six of 57 candidate parties qualified.

/i.s3.glbimg.com/v1/AUTH_da025474c0c44edd99332dddb09cabe8/internal_photos/bs/2022/U/v/OakJiYRSisAbXYH2OSDg/100400434-protesters-hold-banners-as-they-take-part-in-a-demonstration-against-the-military-coup-in.jpg)

Results are expected by the end of January. Whatever the outcome of the vote, a military-drafted constitution stipulates that a quarter of parliamentary seats will be reserved for the armed forces. The lower house, upper house, and members of the armed forces each elect a vice president from among their members, and the joint parliament votes which of the three will be elevated to the presidency.

What happened in the days leading up to the event?

ANFREL says the Union Election Commission, responsible for overseeing the vote, is an organ of the Myanmar armed forces and not an independent entity. The commission’s head, Than Soe, was appointed after the fall of Suu Kyi’s government and is subject to a travel ban and EU sanctions for “undermining democracy” in Myanmar.

Social networks, including Facebook, Instagram and X, have been blocked since the coup, limiting the dissemination of information. The military junta introduced harsh legislation that punishes public protests or criticism of elections with ten years in prison, prosecuting more than 200 people under the new law. Prosecutions were initiated concerning private messages on Facebook, flash protests with the distribution of anti-election leaflets and vandalism against candidate posters.

Myanmar invited international observers to watch the vote, but few countries responded. On Friday, state media reported that a delegation of observers had arrived from Belarus – a country ruled since 1994 by authoritarian President Alexander Lukashenko, who cracked down on pro-democracy protests six years ago.