A decade after Jules Verne published his famous novel “Around the World in 80 Days,” an English traveler embarks on a trip around the world.

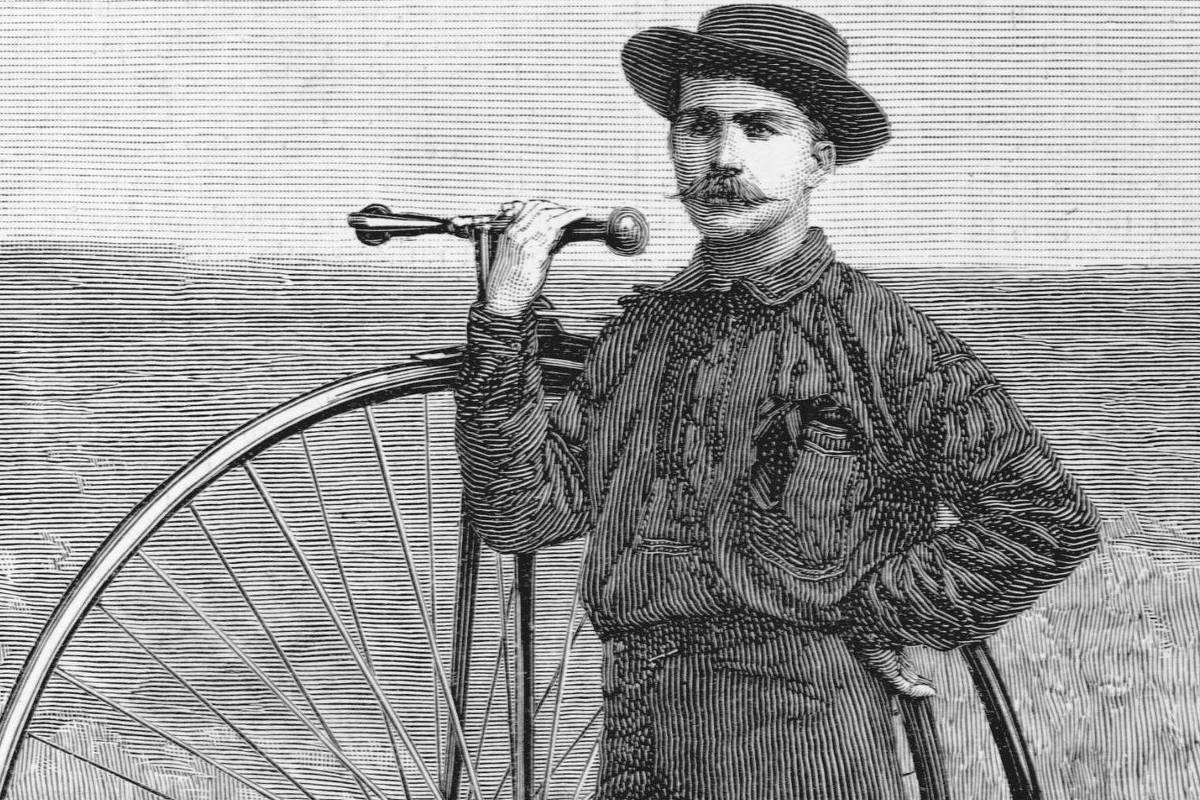

But unlike the character in Verne’s book, who made the journey mainly by train, balloon and boat, Thomas Stevens decided to do it by bicycle.

His journey began in 1884 and lasted more than two years. Back home, he wrote the book “Around the World by Bike”.

In his work, which aroused great interest around the world, he described in detail what he saw throughout his journey across the North American subcontinent, Europe and Asia.

First stop in North America

Born in England, Stevens moved to the United States in 1871, at the age of 17.

He was not an athlete, but he was very interested in cycling, which at the time was considered more of an aristocratic pastime.

According to American writer and filmmaker Robert Isenberg, what made Stevens so popular was the fact that “he was an ordinary man who kept going and had enough motivation to get there.”

Stevens’ original goal was to cross the North American subcontinent, and he did so by cycling from San Francisco (West Coast) to Boston (East Coast) in five months.

After this trip, a popular cycling magazine offered to sponsor Stevens, who decided to expand his trip to circumnavigate the world.

In April 1884, he left Chicago (USA) by ship for England (United Kingdom). After crossing the European continent by bicycle, he crossed Turkey, Iran, India, China and Japan.

Stevens’ bike was very different from today’s. It was a heavy model known as a penny-farthing — a name inspired by two old British coins, the larger penny and the smaller farthing, in analogy to wheels — with a very large front wheel and a much smaller rear wheel.

He was reportedly carrying only a small set of items, such as underwear, a gun, a poncho that doubled as a tent, and a spare tire.

Dating in Istanbul

Stevens arrived in Istanbul (in what is now Turkey) in the summer of 1885 and stayed there during the month of Ramadan (the holy month of the Islamic calendar) in a hotel in Galata, the historic district of the city.

He described Istanbul as one of the most cosmopolitan cities in the world, highlighting the diversity of its people, its streets and its ways of dressing. He also depicted vivid nighttime scenes, with side streets lit only by cafes, as people walked with their lamps in their hands.

Stevens also wrote about women removing their veils and smoking in exclusive compartments on trains and ferries. He even created an itinerary to visit the city:

“An afternoon guided tour of Istanbul includes the Museum of Antiquities, Hagia Sophia Mosque, Costume Museum, 1001 Columns, Tomb of Sultan Mahmut, the famous Grand Bazaar, ‘Pigeon Mosques’, Galata Tower and Tomb of Sultan Suleiman I.”

His writings also mentioned Sufi whirling dance rituals and the residences of the city’s wealthy families. The route taken during Ramadan captures his admiration for the architecture of the Ottoman Empire and the festive lights hung between the minarets of mosques.

During the trip, Stevens got a rare glimpse of then-Sultan Abdul Hamid II, now considered one of the most controversial figures in Turkish history.

“My goal of seeing the Sultan’s face was achieved; but it was only a momentary glimpse.”

In the Gulf of Izmit (Turkey), one of the country’s main industrial regions, he writes that “the villages painted white form an enchanting spectacle at dusk.”

On the roads of the Central Anatolia region, he comes across a camp of Kurdish nomads. The local community impressed him with their generosity.

Stevens described the leader of the group who greeted him as a “dignified hookah-smoking shisha.” He also brought back the food that had been offered to him and the bed prepared without his asking.

True to Stevens’s thoughts on Turkey’s diversity, his account also includes an Armenian priest who gave him a Bible for his travels.

Travel further east

While in Iran, Stevens spent time in Tehran (currently the Iranian capital) as a guest of Shah Naser al-Din.

On the outskirts of Tehran, he stopped to admire the Zoroastrian Towers of Silence, an ancient site where the dead were devoured by vultures because burial was believed to contaminate the soil.

He noted that the fires of Zoroaster had long since died out and that the towers remained a vestige of an ancient religion, as the constantly burning flames were “fed with fuel day and night.”

After Iran, Stevens headed to Afghanistan. However, he was unable to enter the country and so crossed the Caspian Sea by boat to Baku – the current capital of Azerbaijan – and from there he took the train to Batumi, in present-day Georgia.

Then he arrived by boat in the Indian city of Calcutta.

In India, his writings praised the Taj Mahal monument. And although he complained about the heat, he noted that the scenery and colors were his favorite of the entire trip so far.

From there he went to Hong Kong, then a British colony, and then to China.

The final destination of his trip was Yokohama, Japan. There, Stevens met residents he described as refined and cheerful. He wrote: “They are closer to solving the problem of happiness than any other nation. » He also marveled at the children’s love of learning.

It was here that he ended his journey in 1886, which lasted a total of two years and eight months.

By his own calculations, Stevens cycled 22,000 km, becoming what is believed to be the first person to circumnavigate the world by bicycle. He published his travel notes in serial form in a magazine then in a book in 1887.

Effect of orientalism and criticism

While Stevens describes with admiration the communities he encountered, he also draws inspiration from many clichés of the time. He often referred to the people he met as semi-civilized, dirty and ignorant.

In fact, during a visit to Sivas, Turkey, he wrote: “The characteristic state of mind of the average Armenian villager is one of deep, dense ignorance and moral melancholy. »

According to Turkish writer Aydan Çelik, who studies Stevens’s travels to Turkey, he was, like many travelers of his time, an orientalist, that is, someone who viewed the cultures and peoples of the East through a stereotypical lens.

American writer Robert Isenberg believes that Stevens’s outlook began to change throughout the journey. “He’s speaking, of course, from a strict cultural point of view. He’s using this typical Victorian ruler,” Isenberg said. “But when he gets to the Taj Mahal and really admires it, he’s so impressed by the architecture and the art that, for the first time, he doesn’t compare it to anything. He’s just mesmerized.”

As the first person to circumnavigate the world by bicycle, Stevens’ stories were highly sought after in England and the United States. His stories shaped the way many Americans viewed the rest of the world at the time, researchers say.

Stevens’ life became an inspiration to young American adventurers like William Sachtleben and Thomas Allen, who also traveled to Istanbul by bicycle.

Furthermore, Çelik believes that Stevens’ most important legacy was his decisive contribution to the popularization of travel on two wheels, which he described as a kind of bicycle revolution.

Read the original version of this report on the BBC News Brasil website.