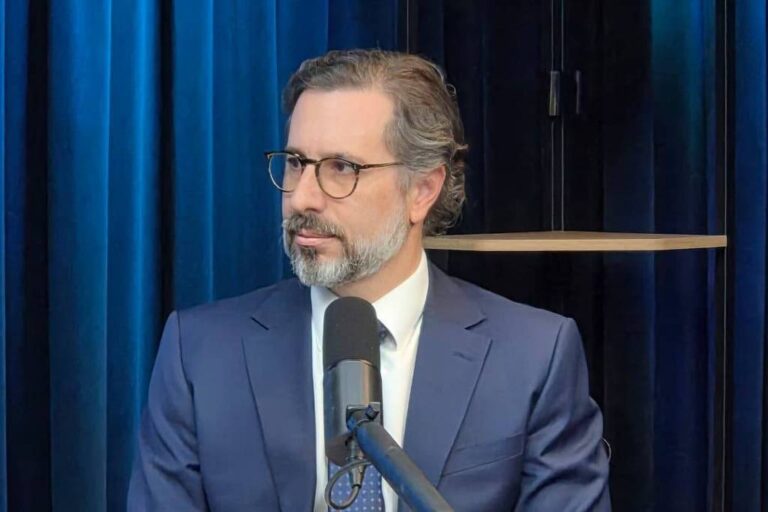

What is common in any creative process is that the idea precedes the object, and not otherwise. However, when the team of Jorge Penadés (Málaga, 40 years old) materialized the Stapleless lamp, the design was a logical evolution on an object that had long obsessed the Malagueño designer. The main tool in question was a small grapher manufactured by the Japanese company Kokuyo in 2009. The patent for this workshop machine, which formalized an American prototype from the fiftieth year, fascinated Penadés for its simplicity and efficiency: thanks to a simple mechanism that created a hexagon on the paper, it was capable of keeping floors last for up to five hours without the need for grease.

A formula as effective as it is durable for stacking and fixing documents without metal waste, which has taken the world by storm and which has been reproduced by a multitude of companies like Muji, with a design for less than new euros. It was clear that he could not abandon his enormous potential and take it to his territory. “What kind of radical simplicity is this? How do you grip the paper without staining it?” he asked me. In the study we always tried to study the life of an object, traveling the path to create something new, and this was a clear case,” explains ICON Design over the phone.

The simplicity that accompanies the original invention was key to the creative process. Without premeditation and only listening to the naturalness of the object. A quality that has defined the world of Penadés since its beginnings and in projects as varied as the collection of pots for BD Barcelona or the design of Camper stores. “I have a certain predilection for simplicity and austerity, as long as it really works,” he asserts with confidence.

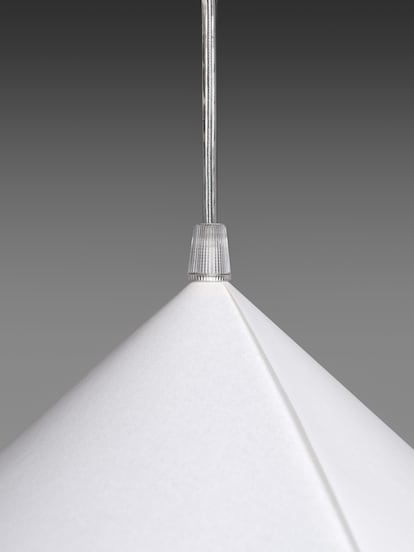

The first phase of the project, continues Penadés, only to understand the limits of the mechanism since it is the thickness, hardness and thickness of the paper that could intervene, in addition to its scale. From the union of three possible elements, without resorting to complex formulas and an infinite number of incisions – “the basis of the machine is to simplify things, to do the minimum to connect the pieces”, he insists – the shape of a tulip was born with three geometric variants: circular, triangular and square. A sharpener in the middle of the paper, and a cut from that hole to one of the corners, would be enough to transform a two-dimensional material into a 3D material.

The choice of material was decisive. With the intention of breaking away from the usual lighting circuit, and advised by friends from the world of graphics, the Penadés team was sold by the technical paper Pergamenata, from the printer Fedrigoni. The factories that produce this Italian company created in 1888 have ECF pulp and FSC® certification, in addition to a cloud effect finish that imitates old parchment. “I always try to use resources from the same industry. If I’m using a machine that greases without grease, which is normally used in a workshop setting and where a lot of printing is evident, we try to rely on suppliers from the same industry.”

Applied like a tulip, this paper creates a homogeneous diffusion of light, suitable for a work space or a dining room. “This allows you to degrade the light point as much as possible and never damage your eyesight, and that’s interesting. When the light gets too close to the paper, it doesn’t dazzle the eyes because it acts as a sort of filter. And as it fades, it continues to refract the light, which provides uniform diffusion, which doesn’t happen with other materials.”

Aesthetically, the absence of a storyline is new. What we can remember first about the technique of origami, how to create paper figures without using sticks or sticks (and which ties in with the Japanese origin of the stapler), are mere conjectures. Its creator insists it is an unrelated anti-design exercise. “I understand that often, even when you get to a minimal, clean object, there can be a very complex relationship behind it, but here it’s completely the opposite. What we had to do was listen to the machine and the material, so they told us where we had to get it from.”

The price, along with the lack of intentionality, is the essence of the Stapleless lamp. Launched at 99 euros and in a limited series of five units (for the moment), this is the second delivery in the series of affordable objects found in stores. online of the workshop. The Déraciné portal, made with harvested olive roots normally intended for wood, started the project at a price of 64 euros. “The idea was to transform these experiments that we do repeatedly in the studio into relatively affordable objects for the people who follow us and appreciate our work. » There is also an excuse, he explains, to initiate conversations with companies capable of publishing these products and producing them on an industrial level.

With a career at cultural institutions such as the Victoria & Albert Museum, Milan Design Week or the permanent collection of the Vitra Design Museum through his Structural Skin project, Penadés’ work is a key piece of the new puzzle of Spanish design. This limited edition of objects with a strong functional component is valuable because it is far from the astronomical figures that lead to this kind of thing, responding to the frustration experienced by the designer during his student years, when he wanted to acquire an author’s design. “Actually, even though it was paradoxical, I thought I couldn’t afford to do my own things,” he reveals. Recently, for years, he organized an ephemeral exhibition, Extraperlo, with affordable objects specially developed by internationally prestigious designers.

For the Malagueño, this new lamp is not intended to democratize design, but rather to provide access to which the public can afford to collect some of its objects. “I don’t go to restaurants, I don’t have an expensive watch or a bottle, but I like it, collecting things from the people I follow. I want to be allowed to work too.”