The first thing they did was stop going to class. He was afraid of being arrested if he left his home. “The ICE came to the top of one of my students and also in no time. After this wine, one day and no more,” says a professor at an institute in Washington DC. This happened in September. In October, they expelled the couple and the priest of their three-year-old son, who decided to leave school to work. Last week, the sole adult responsible for a third student was also expelled, and several teachers began collecting food and money to try to prevent him from dropping out.

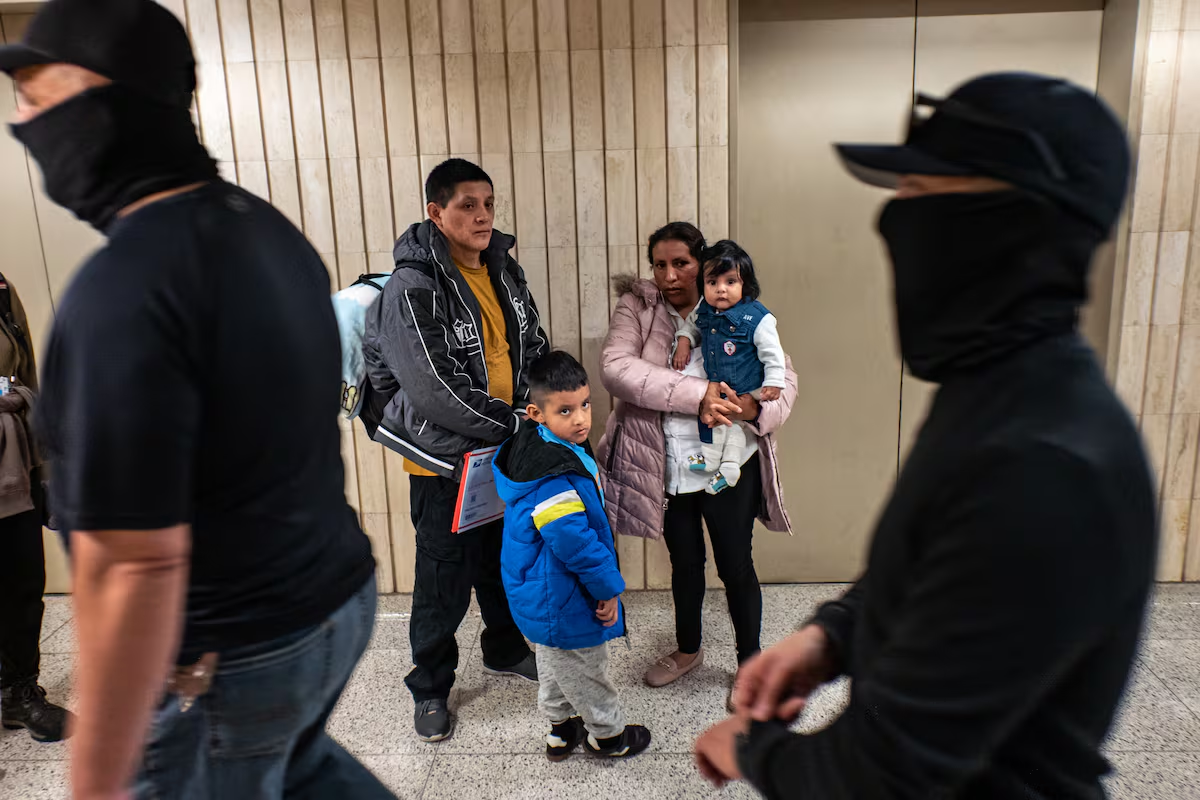

But Donald Trump’s migration offensive on the ground has pushed thousands of undocumented students or students born in the United States to migrant parents to miss classes for fear of being arrested. Many others continue to rush, afraid, having difficulty concentrating and keeping pace, fearing to meet the police at the school gate, or to bring their friends, relatives or family, according to the repression of priests, teachers and psychologists, who warn of the long-term consequences of a trauma that is only just beginning to be studied. Some people have to take on new tasks: taking their little brothers to school, doing the work there.

“At the beginning of the year, several students came to me to ask if they wanted to be expelled, showing me videos on their cell phones. They know that if they go into the street, they can pass. It’s very scary,” explains Professor Vincent Kirk, who teaches English and American literature to teenagers at an institute in Los Angeles, to EL PAÍS. “It’s terrible to see them worrying about this, when they should be worrying about whether or not they can go with the boy or girl they love to the football party at the weekend… They are forced to leave their childhood behind and now they are afraid for their lives.”

Kirk says a third of his students stopped watching when they began Trump-ordered projects in Los Angeles earlier this summer. In response, the movements of the union Maestros Unidos de Los Ángeles (UTLA, by its acronym in English), to which the maestro belongs, have managed to improve this absenteeism, but in many other cities, such as Nueva Orleans, the editorials are only just beginning and this is the moment when the educational community tries to organize itself.

Raids by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents against migrants are revolutionizing schools and institutes across the country, despite the government’s promise not to carry out measures or arrests in or around educational centers. “We see how ICE shows up in schools looking for students, we’ve seen how people go to elementary schools looking for students without a court order,” Kirk assures. Meanwhile, teachers try to continue pretending to be normal, while taking hasty action, diverting students from mental health professionals and preparing and distributing manuals telling priests that they need to be expelled from the country as quickly as possible.

On his first day in office, Trump found himself with a policy banning writing in churches, hospitals and schools, among other places where agents had previously restricted access. However, the Department of National Security maintains that ICE does not make arrests in or near schools. “The media is unfortunately trying to create a climate of fear and smear law enforcement. ICE does not conduct enforcement operations in schools, ICE does not go into schools to arrest minors,” department spokeswoman Tricia McLaughlin said in a statement.

However, in early November, a video went viral in which immigration agents were seen entering a children’s school in Chicago and arresting a teacher in a classroom, denouncing the children, prompting condemnation from the city’s mayor, Brandon Johnson, and Democratic congressmen. Later, the police assured that the teacher was a Colombian immigrant and that they had arrested her because she had committed a trafficking crime. A few days later, I was released to Indiana.

“These are fears that affect all children, on the ground among the children of immigrants, with possible long-term effects,” assures Cynthia Langtiw, clinical psychologist and teacher specializing in minors, migrants and trauma who works with organizations supporting refugees, asylum seekers and detainees. “In the Chicago area, there is a constant sense of fear. At the end of my life, when my own daughter was walking to school, at 7:30 in the morning, they arrested one of our children.” Just before, his 17-year-old son had sent him a photo showing him that he did not want to leave the institute because there was a bad word.

In California, a Stanford University study was the first to prove that this year’s increase in essays in the state coincided with a significant increase in student absences, particularly younger students. “It is very important that people understand the social and economic impact of these policies. Missing school is harmful to children, at a time when assistance was available within hours of the pandemic. But there are many other reasons why it is harmful, and the most important is psychological trauma,” warns Thomas Dee, author of the survey, in conversation with this periodical.

Another study from the University of Rochester (New York) found that when migrant arrests increase, the grades of Bajan Latino students, even those written in the area where the school is located. Indeed, previous surveys have demonstrated that children from immigrant families are four times more likely to have suicidal thoughts and attempts, and that those who have emigrated have a greater likelihood of suffering from depression and anxiety.

“It scares me that my priests are leaving the house”

“I should be focused on school and I can’t concentrate. I’m afraid my priests will leave home, because I can’t decide to decide them later and never see them again. I don’t want to live like this, I’m 16, I shouldn’t be afraid.” It was with these words that Manny Chavez, a high school student from Hillsboro, Oregon, traveled the country after a video of the teen speaking at a meet-and-greet in his neighborhood went viral.

“We fight for our rights and treat ourselves like animals. We are judged by the color of our skin and the way we speak. And we have a president who acts like a child and doesn’t stand with us for what he thinks of us. It’s like a feverish sweat, except we all know it’s true,” the teenager said between tears.

Not long before, ICE had arrested family members of their friends and members of their soccer team, as well as teenagers at gunpoint at a coffee shop in their town. In October alone, ICE arrested more than 300 people in Oregon, the majority in the Portland area, where Hillsboro is located and Latinos make up a quarter of the population.

As a result, psychologists and other mental health professionals warn that juveniles with nutritional and nutritional problems are proliferating and it is time to play, build relationships and get out on the streets. But the main side effect of this situation is, emphasizes psychologist Langtiw, what we call “betrayal trauma”: that which finds its origin in someone who trusts the victim.

“The layers of this trauma are even more deceptive because the person who is supposed to take care of you is the one who is hurting you, which makes it even more difficult to escape. This is what many children experience today when they come to their arrested neighborhoods, even if they have never committed a crime,” he reports. “When the government is supposed to take care of you, feed you, support you and help you, it’s a betrayal trauma on a societal level. That’s why we need to pay attention to the long-term effects.”

Experts recommend that priests continue to talk to minors about issues that concern them, as well as turn to professionals if they need psychological help, and schools ask them to try to guarantee minors’ basic needs, such as their food or health care. “If students are absent from class, they need to try to find ways to continue learning so they can keep up when they return,” said Hedy N. Chang, founder and executive director of Attendance Works, an organization leading a campaign calling for truancy to be considered a public health issue.

Some schools have ordered their staff to close all doors and not allow immigration officers to enter unless subject to a court order. “We funnyly saw a teachers’ cloister where they told us that we cannot leave the nadie, because it is the only protection we can give to our children,” says another teacher from a school in Virginia. “We also asked families to allow as many adults as possible so that in an emergency, if something happens to the father or mother, any adult can take the child home.”

Precisely, the measures that schools and institutes take to try to protect students can also be a tool in the fight against trauma, according to experts. In San Diego, a group of teachers decided to patrol the streets before dawn to check for ICE agents in the area after arresting several student priests. In Los Angeles, an inspector created “security perimeters” at graduations, protected by district police, to prevent possible attacks that could spoil the parties.

But many people prefer not to take risks. Several teachers interviewed by this periodical report that the families of some of their students have decided to return to their country of origin. “I suspect that when we get the data back from this school year, which is normally collected in the fall, we will see that many of the most affected districts have significantly fewer students enrolled,” says Professor Dee. “Families will walk instead of facing the risk that separates them. »