It is known by its English abbreviation: BIVP (Building Integrated Photovoltaics) and translates to building-integrated photovoltaics. It is not a new technology, on the contrary, it has reached maturity and has been installed for years in various constructions in every way. … the world. It consists of integrating photovoltaics into materials and architectural elements of buildings. There is already glass, ceramic sheets, bricks, tiles and composite materials…that capture sunlight and convert it into energy. They are installed on facades, roofs, windows, skylights, pergolas, awnings…

A solution with great potential to decarbonize buildings (and their city facilities), which also pollute. At European level, it is responsible for more than 36% of CO2 emissions and 40% of final energy used. However, despite this promising future, BIPV has not taken off with the strength that matches its potential and is well below the pace of the PV sector as a whole.

It remains a niche market, with numbers to attest to that. In fact, according to International Energy Agency (IEA), Europe recorded approximately 350 MW of installed capacity in 2024 using this technology, representing less than 1% of the total distributed PV capacity installed that year. (Distributed generation is the production of electricity from several small power sources located near points of consumption, for example from homes and buildings.)

BIVP technology has advantages that make it unique, because in addition to generating green energy for the building’s self-consumption (thus reducing the electricity bill), they are usually solutions that do not sacrifice architectural design (since they offer an increasing range of colours, textures, finishes, transparencies…) or useful space (traditional photovoltaic panels require more space), which is very important in densely populated cities.

City aesthetics

“We live in cities where there is nothing worthwhile to achieve sustainability. These BIVP products align energy needs with creating pleasing environments and allow a great deal of freedom for the architect. If we think about traditional photovoltaic panels, they are the same air conditioning units that we have installed, which make cities ugly. “BIVP aims to offer clean generation without affecting the aesthetics of the city,” comments Lorenzo Olivieri, professor and researcher at the Higher Technical School of Architecture and the Solar Institute of the Polytechnic University of Madrid.

According to the International Energy Agency, we have 90 European manufacturers operating in national and local markets. The IEA highlights the case of the Spanish company Onyx Solar, which has projects around the world. “BIVP is mainly manufactured in Europe, and this constitutes a competitive advantage over traditional PV panels made in China,” says Olivieri.

However, BIVP systems do not fully penetrate the market. They have to compete with traditional materials used in construction, which are usually cheaper and better known to architects. “In addition, there is a lack of expert professionals, specific training and incentives to promote the use of these solutions,” believes Olivieri.

Integrating this technology into regulations is also a challenge, suggested Paula Santos, Director of Energy and Electricity Communities at UNEF (Spanish Photovoltaic Federation). “BIVP technology is an element of energy generation and therefore self-consumption and must follow these regulations, but at the same time it is a construction element. This work of establishing all the common rules must be done. He believes that these facilities require specific regulation.

According to Santos, the regulatory push will come from including these solutions in the Technical Building Code, the set of rules regulating the construction of new buildings and the expansion of existing ones, and in the National Building Renovation Plan being prepared.

This technology does not affect the architectural design or the useful area of the building.

With its photovoltaic glass, Onyx Solar, a SME based in Avila since its inception, has revolutionized the market to the point that it has become an international standard. Its solutions can be seen in a wide variety of buildings around the world, many of which are iconic. With more than 500 projects in 80 countries, it has integrated PV technology into buildings such as Dubai’s iconic torch, Madrid’s Royal Theater, and Sydney’s St Andrew’s Cathedral (which is more than 200 years old). In the Sensoria Tower, the largest hotel in Dubai, more than a thousand pieces of photovoltaic glass have been installed representing the company’s logo, and there are another 4,500 square meters of the same material on the facade of the luxury residential complex 262 on Fifth Avenue in New York. Even McDonald’s at Disney World has photovoltaic glass from Onyx Solar. They are found in hospitals, hotels, universities, sports centers, office buildings, city halls, shopping malls, subway stations, data centers and even schools, private homes and sheds. In fact, companies like Apple, Microsoft, HP, Novartis, Samsung, Coca-Cola, Heineken, Merlin Properties… have trusted this technology.

Architectural glass

“It is an architectural glass that meets building regulations in terms of safety standards, thermal and acoustic insulation and mechanical resistance, and we have integrated photovoltaic technology with it,” explains Teodosio Del Cagno, Technical and Operations Director at Onyx Solar. In this way, the possibility of generating clean energy is added to the passive properties of the glass, as a solar filter, facilitator of interior comfort and insulation, which is a great advantage because it can help reduce the electricity bill of the building in which it is installed. “It can save 30 to 40 percent of a building’s energy needs,” Del Caño says.

Onyx Solar photovoltaic glass has other advantages that make it a guarantee of its success: it is an element that is widely aesthetically accepted by architects, because it is a product that can be customized with colors, transparencies, shapes… and has no restrictions when it comes to integrating it into a facade, skylight, window or canopy. With many projects around the world, it is a powerful and proven technology. In addition, it reduces the carbon footprint because “this material generates its own energy for 35 years, so that after three and a half years all the energy needed to manufacture it is generated, so from that moment on, its carbon footprint is zero,” explains Del Caño. He points out that the return on investment is quick, “between 3 and 8 years.”

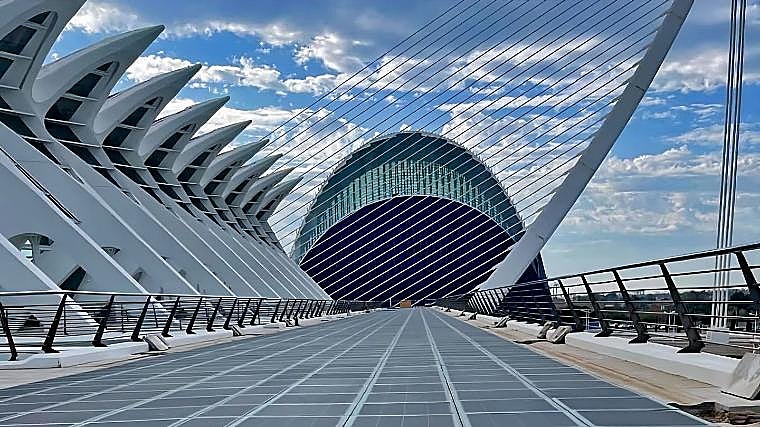

Onyx Solar has installed more than 6,000 square meters of walkable PV cantilever pavement at the Valencia Science Museum

Onyx Solar is also working on new lightweight materials, such as composites, which could incorporate photovoltaic technology. “Maybe the future is that PV integration in architecture is facade spray painting,” Del Caño smiles.

Complete customization

The Basque startup Izpitek was born after a decade of work between technology center Tecnalia and Branka Solutions. It has several patent families for integrating photovoltaic technology into buildings. On the one hand, it designs, develops, manufactures and brings to market its own solution based on the encapsulation of photovoltaic cells in composite materials. “We have achieved a homogeneous coating (fibers mixed with resin), which protects the photovoltaic cells well with the properties of the composite. It is also a transparent, light and flexible material. “They can be from tenths of a millimeter to several millimeters thick, and adapt to curved and flat surfaces and odd shapes,” explains John Lassa, co-founder of Izpitek. It even allows customization: “We can laminate many different types of cells – he highlights – and make custom-made designs. With different color finishes, matte or glossy, we adapt to geometric shapes…».

According to the IEA, there are 90 manufacturers of these solutions in Europe and we have 350 MW of capacity

This new material can be integrated into existing roofs or as solar tiles covering the enclosure. On the facades the cladding is the second skin of the building. “We do not replace the building cement but rather integrate it as an external skin in the ventilated facade, in an aluminum sandwich, wooden or ceramic element,” Lassa explains.

Izpitek has also developed the integration of photovoltaics into glass sheets as thin as a sheet of paper and into existing glass. “Our solutions are found in unique constructions, in private homes, skylights, pergolas… and also in mobility, from funicular tracks to the roofs of refrigerated trucks or caravans,” he adds.

Flexible brick canopies in a commercial and office building in Australia. This company has integrated photovoltaic cells into this material

Catalan company Flexbrick has developed and patented ceramic panels that are installed in buildings like a brick curtain and that adapt to each project. They can reach 30 meters in length. “They are nets that block sunlight from buildings and form an outer shell. “They can be customized with textures, images, logos, colors, shapes…”, notes Rafael Pardo, Technical Director of Flexbrick. In this innovative solution, a further step has been taken by integrating silicon photovoltaic cells into the bricks.

Brick curtains

This brings many advantages: brick curtains have low maintenance and high durability; They are easy to install, disassemble and repair. They can be recycled, and because they are prefabricated, they have a high level of customization, which is a very attractive aspect for playing with architectural aesthetics. “It can be installed with a crane within three weeks, which makes a lot of sense for unique buildings and hospitals… Our system installs quickly and reduces installation time, thus generating a lower carbon footprint,” Pardo highlights. To these advantages, Flexbrick has added clean energy generation using photovoltaics to its net curtains. “Now the building materials themselves are becoming active. “It’s a useful way to remove carbon,” Pardo defends. Energy is generated at the point of consumption and in proportion to the building’s needs.

Currently, Flexbrick has carried out several demonstration installations of this new solution. “Our system is installed in a checkerboard pattern. Thanks to this 50% transmittance and our photovoltaic cells, which are not integrated into all types of bricks, we have achieved a level of energy production equivalent to 350-400 watts per square meter. “If a building has sufficient envelope, it is easy to provide it with the PV energy it needs to consume,” Pardo says. Flexbrick has incorporated this technology into the pavilion being built to celebrate Barcelona’s World Capital of Architecture in 2026. “A highly parameterized building with a Catalan vault where the brick edge becomes a photovoltaic pergola,” says Pardo. A new version of photovoltaics is making its way into the engineering of the future.