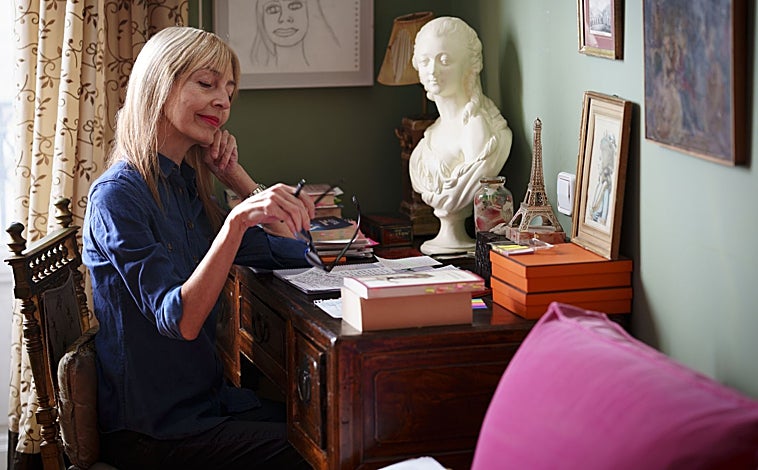

The house of Amparo Llanos (Madrid, 1965) is a huge library. A temple of literature located in the heart of Madrid, next to Puerta de Alcalá. There is no wall without books, and many more are scattered around the living room tables. … or in the small 18th century office where he translated, by hand, Jane Austen’s letters published by the Renacimiento publishing house on the occasion of the 250th anniversary of her birth. “Honestly, I don’t know how many I have. A lot. I sometimes started to count them, but I get lost and forget,” admitted the co-founder of the Dover group, with her sister Cristina, in 1992.

Nearly four shelves are dedicated to the British author, whom she places on the podium of the most important writers in history: “For me, the three geniuses of universal literature are Shakespeare, Cervantes and her. Without a doubt. Not in that order, because there is no first or second place. They form a trinity, even though Austen was treated with indifference for almost two centuries by a patriarchal society that could not tolerate there being a woman between these two authors,” explains Llanos.

On the table where she posed for photographer ABC, we see the original edition of “Letters to a Young Woman,” published by Jane West in 1806. Nearby, an entire column devoted to Virginia Wolf and other shelves – “organized in my mind” – with hundreds of works of philosophy, psychology, history, music and literary criticism. “This is my feminist library,” she proudly announces. The room looks like an old dressing room, but it is invaded by hundreds of books filled with post-its and accompanied by portraits of Isadora Duncan, Charlotte Bronte, Simone de Beauvoir, Marguerite Duras, Claude Cahun, Emilia Pardo Bazán, the 16th century Italian painter Lavinia Fontana and even the actress Kirsten Dunst.

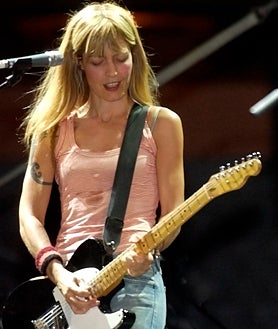

Stuck in a corner is a tiny television that he hasn’t turned on for fifteen years, he says, and which he wants to get rid of to put up another shelf with books. Perhaps the copies of “Yours Affectionately, Jane Austen” that she has stacked on a chair near the entryway. He comments on it while laughing, as if it shames him. There is also no trace of guitars or records: “I have a lot of them, but in bags stored in the closet. “I don’t have walls for everything.” We don’t even see his group, the only one on the Spanish independent scene which, in the mid-90s, driven by the Nirvana tsunami, enjoyed commercial success with more than two million records sold and tours throughout Europe and America.

—What was the first thing you read by Jane Austen?

— “Sense and Sensibility” (1811) when he was 32 or 33 years old. My parents did not come from Anglo-Saxon literature, but rather Spanish, French, Russian, American or German. But then I read his novels in one sitting and reread them a thousand times. I remember thinking that he hadn’t missed a single sentence, that was incredible. Everything seemed perfect to me. What fascinated me about her was that she knew how to describe the human condition like no other. Their characters were real, they were full of life.

-

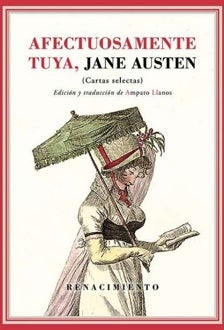

Editing and translation:

Amparo Llanos -

Editorial:

Renaissance -

Pages:

224 -

Price:

17 euros

— Well, until recently, it was vilified, as if it were corny, romantic literature…

— It’s incredible that this lie has caught on. And this continues to happen. Since the release of “Yours Affectionately, Jane Austen,” some men have told me that they bought the book for their wives, as if it were third-rate literature just for women. For women? It’s universal literature! An early 20th century English critic established a person’s level of intelligence by asking whether or not they liked Jane Austen. I do it all the time, but with Jane Austen and the Beatles (laughs). If someone tells me the Beatles are terrible… Ugh! This one no, no, no. I know it’s a bit “snobbish”, but I can’t help it.

— That’s why I put him on the same level as Cervantes and Shakespeare.

— Yes, I understood that very clearly. When I read “Don Quixote” and Shakespeare’s tragedies, I feel the same way I did with Austen. These are the three most perfect writers when it comes to describing the human condition in words. Their characters are unique and, at the same time, they connect to everything that makes us human, to what we have in common. It’s very difficult for me to achieve this and I think these three are the ones who do it best.

—What is your favorite Austen novel?

— “Emma”, perhaps because it is the longest and has the most beautiful sentences. Any of his novels make you smarter, because he says smart things all the time. With “Emma”, this feeling is continuous, but there is not a novel that I do not like. I love “Mansfield Park” and “Pride and Prejudice” is “short and sparkling,” as she said. The worlds he creates are delightful, but I never want “Emma” to end, I want to live forever in Hartfield, the protagonist’s town.

—Was this first experience as a translator difficult for you?

—I sweated from the Indian ink, but I enjoyed it. In fact, when I had half the letters translated, I translated them again with what I had learned. That’s actually how I started at Dover. When I found a guitar riff, I was like, “I love this, but I’m playing it wrong.” Then I started working hard to learn it, fought carefully, and when it came time to record the album, I took it to the studio perfectly. Well, with Austen, the same, I put all my energy into it, even reading a lot of essays on translation.

—When you created Dover, did you dream of making a living from music or was literature your priority?

—Cris and I didn’t dream of making a living from music, just of creating songs. Recording an album seemed like a bomb to us. Besides, if we sang in English like us, it was unthinkable to make a living doing that.

— Given this quantity of books, it seems that he dreamed of publishing a novel and not an album.

— It wasn’t in my head either, to be honest. I wouldn’t be able to write a novel, that’s for sure. I have read the greatest, starting with Jane Austen, who for me is part of this trinity of universal authors, and I do not have the necessary talent. However, as I had always loved literature, I was encouraged to translate, as it did the important work. It’s not that it’s easy, but I just need a good command of the language and respect for whoever you are translating, not talent. That’s why I dared.

—As a voracious reader, perhaps you have set the bar too high for writing fiction…

— I don’t really have the makings of a novelist. Nor as a poet, although he wrote song lyrics. It has nothing to do with poetry, it’s something completely different that has much more to do with music. I don’t know if, as I get older, I will consider that I have something to say, for example in an essay.

—Her sister, Cristina, is also a big reader. Who instilled this passion in you?

—As a child, my daily routine consisted of playing for a while, doing homework, taking a shower, eating dinner, and reading. He didn’t miss a single day. My mother always made sure to buy us good books. As a teenager, I began reading everything she read religiously. He said to me: “Why are you trying ‘La familia de León Roch’ (1878), by Benito Pérez Galdós? I think you will like “Mother Nature” (1887), by Emilia Pardo Bazán. And from there to Mercè Rodoreda, Flaubert, Dostoyevsky… I loved him very much, I trusted his judgment and I read everything with devotion. We loved this intimate relationship that we had through literature. Cris, who is the youngest of five siblings and me the eldest, ten years apart, always says that it was me who gave her that passion when we started spending so much time together on the Dover tours.

— If I’m not mistaken, Cristina is writing now.

-Yeah. He wrote a sort of diary, I can’t tell you more about it. You are looking for an editor.

“Don’t you miss Dover?”

— Cris and I thought we had already said everything we had to say, that’s why we never saw each other again. We look ahead and Dover is no longer there. I’m proud that I didn’t come back for money, as they offered it to us several times. When they started doing shows at the Bernabéu, they offered us to play in 2027, on the 30th anniversary of “Devil Came To Me” (Subterfuge, 1997), but we didn’t even think about it. Cris blurted out, “Ooooh, how sweet!” (puts a soft and sincere voice), but he didn’t even ask for the amount. I told them that no matter how much money they put on the table, it wasn’t going to happen. Two years ago, same thing, another fortune. Even though they accused us of being sold out, the money never came to us. Of course, we wanted the one that suited us, even if that wasn’t what pushed us to compose and give concerts.

— Have they earned enough to remain calm a decade after the dissolution?

— Yes, we earn a very good living. We were incredibly lucky, because we were able to demand good contracts and we worked a lot in Spain and abroad, which didn’t happen to all groups. And with Dover’s characteristics, being female and singing in English, it seemed unthinkable to be able to make a living from music, but we did it.