Joan Manuel Serrat says that his exile in Mexico, due to persecution by the Franco regime, was a “time of poverty”. “In the sense that I hardly wrote anything, I didn’t write any songs,” he explains. It was a time of solitude, when he had to cling to “holds,” he said, like those he found among the Spanish exiles in Mexico. “People who helped me understand things better and learn,” he told this newspaper minutes after the Ateneo Español de México, the institution that perpetuates the history of Spanish exile, named him an honorary member on Monday. “It’s the memory of sadness, of lost time, but also of time fought,” says the Catalan.

A plaque in his name now appears alongside other distinguished members of this institution. Monday morning was an intimate and moving ceremony. It was quite a gesture on the part of the singer-songwriter to open a space in his diary to receive this tribute after the hustle and bustle of the Guadalajara International Book Fair (FIL), where he shone as one of the most anticipated and applauded figures of the literary meeting. In the city of Guadalajara he also obtained his doctorate. Honoris Causa from the University of Guadalajara (UdeG) and on Monday he remembered some of the words he had spoken during this other tribute: “May the Mexico of books beat the Mexico of weapons and violence”.

He said this while looking out at the balcony of the beautiful Porfirian house that houses the Ateneo headquarters in Mexico City. There were two groups of children’s choirs, to which Serrat winked: “I invite you to take advantage of the opportunity, to take advantage of the time and to work to build a future for yourself as good citizens, which we still need so much,” he told them. These children, students of the Luis Vives Institute and the School of Madrid, entertained the artist by singing songs from the Spanish Civil War, such as the one that recalls: “If you want to write to me, you already know where I am: on the battle front, first line of fire.” Because the memory of the war was present, with its desire for victory and the pain of defeat. “If Spain had gone straight from 36 to 37 without war, we would have had a different future, very different from the one we had,” Serrat told this newspaper.

It was Alonso Leal, treasurer and legal member of Ateneo, who recalled during the tribute what Serrat’s music represented for the Spanish exile. “It was an indispensable element of our sentimental education,” he said. “His date of birth indicates that Juan Manuel Serrat was born and raised under the Franco dictatorship, an experience that united and continues to unite him with the Spanish republican exile,” he added and, as an example of this alliance, he recalled that in 1975 the Mexican government publicly condemned the last executions of the Franco dictatorship and took a series of economic measures against the regime. “Serrat, who was in Mexico, condemned these events and expressed his solidarity with President Luis Echeverría. It cost him a year of exile in our country due to the search and arrest order issued against him by the Franco government,” recalled Leal and added: “Thus, Serrat tasted the bitter bread of exile, as had happened to his compatriots 36 years before, and he confessed himself that it was a very difficult period of his life, because he lived with “the constant worry of not knowing if one day at that time he would be able to return to his land.

A shared experience, that of exile, that Mariángeles Comesaña, vice-president of Ateneo, also recalled. “I am with a friend who, since adolescence, has given me and my entire generation the privilege of finding a place to realize our dreams,” he said. “These little things, how great they are in the waves of your music, Juan Manuel. In the plains of solitude, the one that appears at 15 and 16 years old, when we were young, we turned to your voice lulling the word of Antonio Machado’s time, expressing the inevitable future that we all share. This is why it is so natural that Machado’s verses find their other voice in your melodies. They are melodies that come from the deepest verse to melting into the air like soap bubbles, without a doubt, you make the word into a song and the song into a word,” he told her.

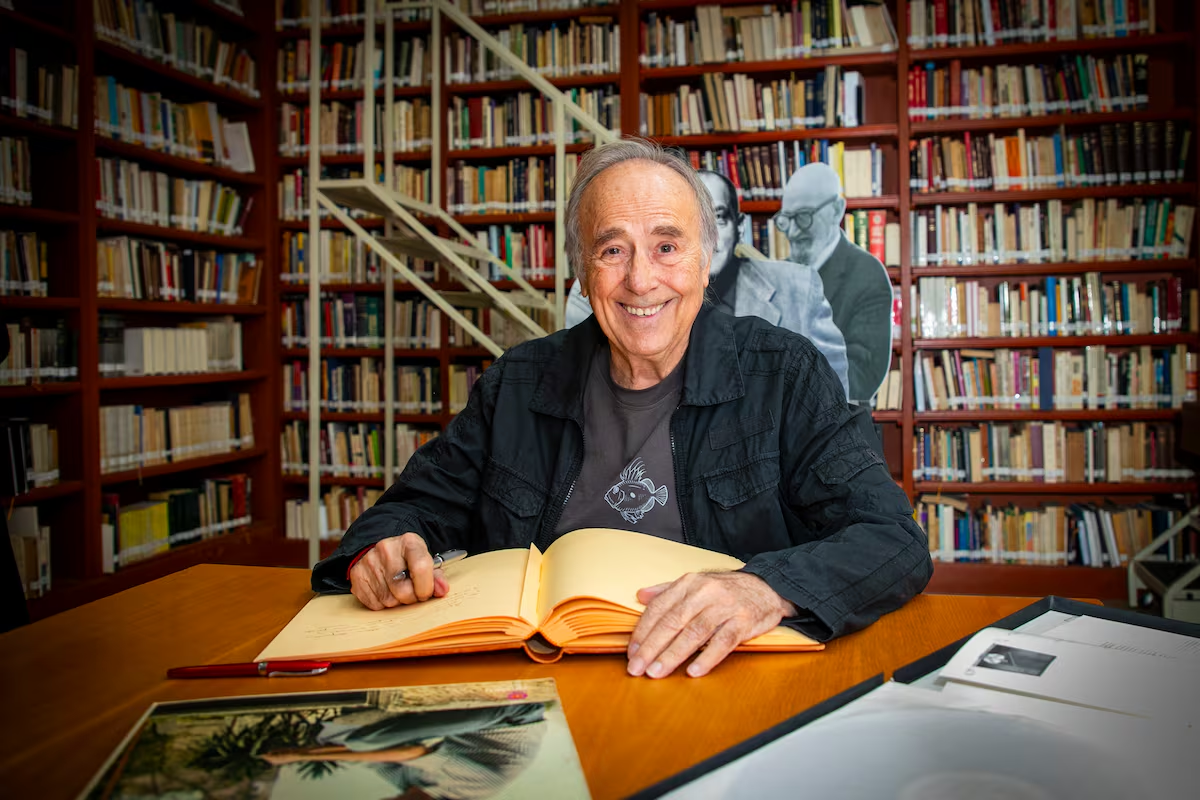

Serrat takes the opportunity to explore the corridors and spacious rooms of this neoclassical style residence. He saw his plaque on the wall of honor and was able to turn the pages of the book which keeps the memory of the ships loaded with Spaniards who landed in Veracruz. Then he spoke to this newspaper.

Ask. As an exercise of imagination, if you now had the time to speak to one of these exiles, what would you tell them about the homeland lost and the homeland found?

Answer. I was here, living among them and I knew exactly the bitterness of the lost homeland and not only of the homeland, but of the landscape, of the perfume, that is to say that the loss is total in an exile who does not know when he will return. But it is even deeper when the exile continues over the years and the exile needs to know that the provisional homeland is not simply a provisional homeland, but that it is the homeland of his present with all its consequences.

Q. What did exile mean to you?

A. It was a time of poverty, in the sense that I hardly wrote anything, I didn’t write any songs. I made an effort to stay active so as not to lose what grip I had left. And I was also lucky to find support from people from the Spanish exile in Mexico, with whom I had excellent contacts. The Taibo family and everything that people like Buñuel, like (writer Juan) Rejano, like (screenwriter Luis) Alcoriza, represented, in short, a lot of people who helped me understand things better and learn.

Q. What does this plaque mean to you?

A. All the plaques here are the result of sadness, loss, wasted time, but also, in some way, struggle.