The Mosque-Cathedral of Córdoba has been a source of inspiration for many of the city’s legends and, more than 1,200 years after its construction, it continues to hide secrets both for the inhabitants of Córdoba and for a large number of visitors which welcomes each year … this world heritage site – in 2024, there were 2.19 million, its record.

The Cathedral Chapter, responsible for its management and maintenance, is considering an idea aimed at improving the sustainability of the site with an element long sealed underground: the reactivation of an underground well to collect rainwater and its subsequent reuse. In other words, bring back to life a structure that remained hidden for centuries under the Patio de los Naranjos and whose existence is little known to Cordobans. Although the operation is technically difficult, in the first sustainability report of the monument, presented this week, it is indicated that “its reactivation is currently under study for the collection and use of rainwater which is channeled through the roofs of the building”.

In the patio, almost camouflaged by the paving stones, there are three stone slabs which lead to an underground space where a cistern from the Caliph era remains. Unlike a conventional well, a cistern does not extract water from the basement, but rather serves as a large reservoir intended to store rainwater. That of the Mosque-Cathedral has a capacity for 1,237 cubic meterswhich is approximately half the size of an Olympic swimming pool.

Belén Vázquez Navajas holds a doctorate in archeology from the University of Córdoba, who studied his thesis on hydraulic archeology in the western suburbs of Umayyad Córdoba. It included a section to talk about the cistern, built under Almanzor’s mandate (976-1002). He ordered the construction of eight additional naves along the entire length of the west side of the mosque, including the patio, which was to be extended towards the east. Below, he tackles the underground cistern intended to collect rainwater in Cordoba.

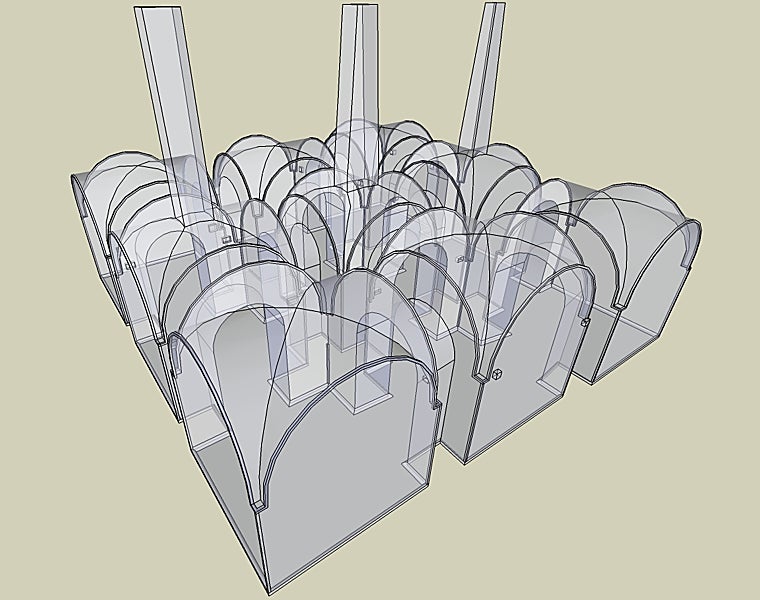

3D design of the underground cistern

The cistern is six meters deep, with a square plan and 15 meters on each side. As the archaeologist details, “it was built with calcarenite cut stones and was entirely covered with lime mortar painted with almagra. It is divided into nine covered spaces by edge vaults. These spaces are separated by cruciform pillars one meter wide, linked together by semicircular arches.

Access to the cistern was through three ports, located in the Patio de los Naranjos. Currently they are sealed with fully visible stone slabs. An element which goes almost unnoticed by visitors and which hides underneath another example of Andalusian architecture. It contributes to further enriching the world heritage site of the Mosque-Cathedral of Córdoba.

As the expert explains, “the creation of the cistern was probably due to the need to increase the water supply to what is today the historic center of the city. “Not just from the fountains and ablution basins of the mosque itself.” considered the possibility of reactivating the tank as an example of efficiency in the use of water in the monument although its technical feasibility is too complicated.

Although it was one of the most important cisterns of the time, the construction of these types of structures was not exclusive to al-Andalus, as they had already been carried out before. “The cistern of the Mosque This is not a pioneering construction as such, but we must consider it one of the great works of Andalusian engineering given its large dimensions”, explains Dr. Vázquez.

The cistern under the Patio de los Naranjos is one of the largest in the Mediterranean

This cistern has a storage capacity of 1,200 cubic meters, but there were other cisterns (domestic and community) in al-Andalus and even in the Umayyad Caliphate of Córdoba, but of smaller size. “The one under the Patio de los Naranjos is one of the largest medieval cisterns in the Mediterranean», assures the archaeologist.

“It was always there,” he says. But with time and non-use of it, it has gone unnoticed. Even if it has not escaped the passage of the years and has been object of repair to improve its watertightness at certain periods of history. Depending on what is included in the first sustainability report of the mosque-cathedral – which reflects its recovery as a possible future measure – and the challenges of the 2030 agenda, the cistern could have a second life even if it is difficult.

There is no data on its operation since written sources only mention its construction. However, “we understand that rainwater collected in the canals located on the roofs of the mosque’s prayer hall was transported to the cistern through canals or pipes.” These chains are still standing with reforms over time.

Storm Claudia last November left a clear picture of the functioning of the system of canals and gargoyles on the roof of the Mosque-Cathedral. These infrastructures made it possible to evacuate the heavy rains of the storm, leaving a spectacle visual of “rivers of rain”.

The network of canals, strategically located on the bridges, collects and directs water to specific outlets. through the gargoylespreventing it from accumulating and damaging the building. Sloped roofs and gutters channel water into pipes that flow into street-facing sewers. This water, during the time of Almanzor, was stored in the underground cistern to be reused later.

“There could be sinks in the patio to collect rainwater, but they are not physically checked,” explains the doctor. “Some experts do not exclude parallel provisioning via urban pipes such as those coming from the remains of the sources supplied by the Qanāt des Eaux de l’Usine Cathedral, but it is not possible to verify this scientifically,” he explains.

The metal stairs to access the interior of the tank

Why can’t you visit it? Access to the cistern is only through a few open skylights in the patio, now covered with stone slabs. Thanks to these particular skylights, one can access excessively narrow vertical tunnels which lead to the lid of the cistern. However, given its small size, access to it is today complicated and impractical for the general public.

More than 45 years ago, the archivist of the Cathedral, Manuel Nieto Complimentand one of the two conservative architects of the temple, Gabriel Ruiz CabreroThey entered the cistern, armed with flashlights, without knowing exactly what they would find. 15 years ago, Ruiz Cabrero explained that currently the flow of rain is diverted to the sewer system, but that engineers working under the tutelage of leader Almanzor connected the downspouts to the cisterns.

Both knew of the existence of the cistern thanks to the abundant literature that the monument had always generated, and especially thanks to the research carried out by Félix Hernández in the 60s and 70s of the 20th century. The cathedral archivist, who died four years ago, remembers it: “Félix I went down to the cisternshe was the one who cleaned them and provided documentation about them.

Interior of the cistern. built by Almanzor in the 10th century

For his part, the architect Ruiz Cabrero He explained that the expedition was made “through a metal ladder and we did not know how much water it could contain: we checked on the way down that leaf was from shallow depthbecause the water which arrives from the roofs to the collector located on the facade of the cathedral no longer goes to the cistern, as it did during its construction.

Experts assure that the use of the tank was purely functional and never aesthetic. The caliph intended to guarantee that even in times of drought, there would be no shortage of water in the ablution courtyard, where the faithful had the obligation to purify yourself before starting prayers. It is ruled out that the cisterns were designed for human consumption, although this was a working hypothesis of scholars at first, given the long periods of scarcity of rain in the city during the various stages of the Caliphate.

In 2010, as ABC Córdoba reports, the Cabildo studied the possibility of making the cistern visitable, although the idea ended up diluted over time. Experts were already reluctant and not very optimistic about the idea because access is really complicated. To access, A ramp should be provided to facilitate accesswhich can now only be done using the metal ladder. It would be necessary to raise one of the slabs located in one of the two avenues or alleys that cross the Patio de los Naranjos.