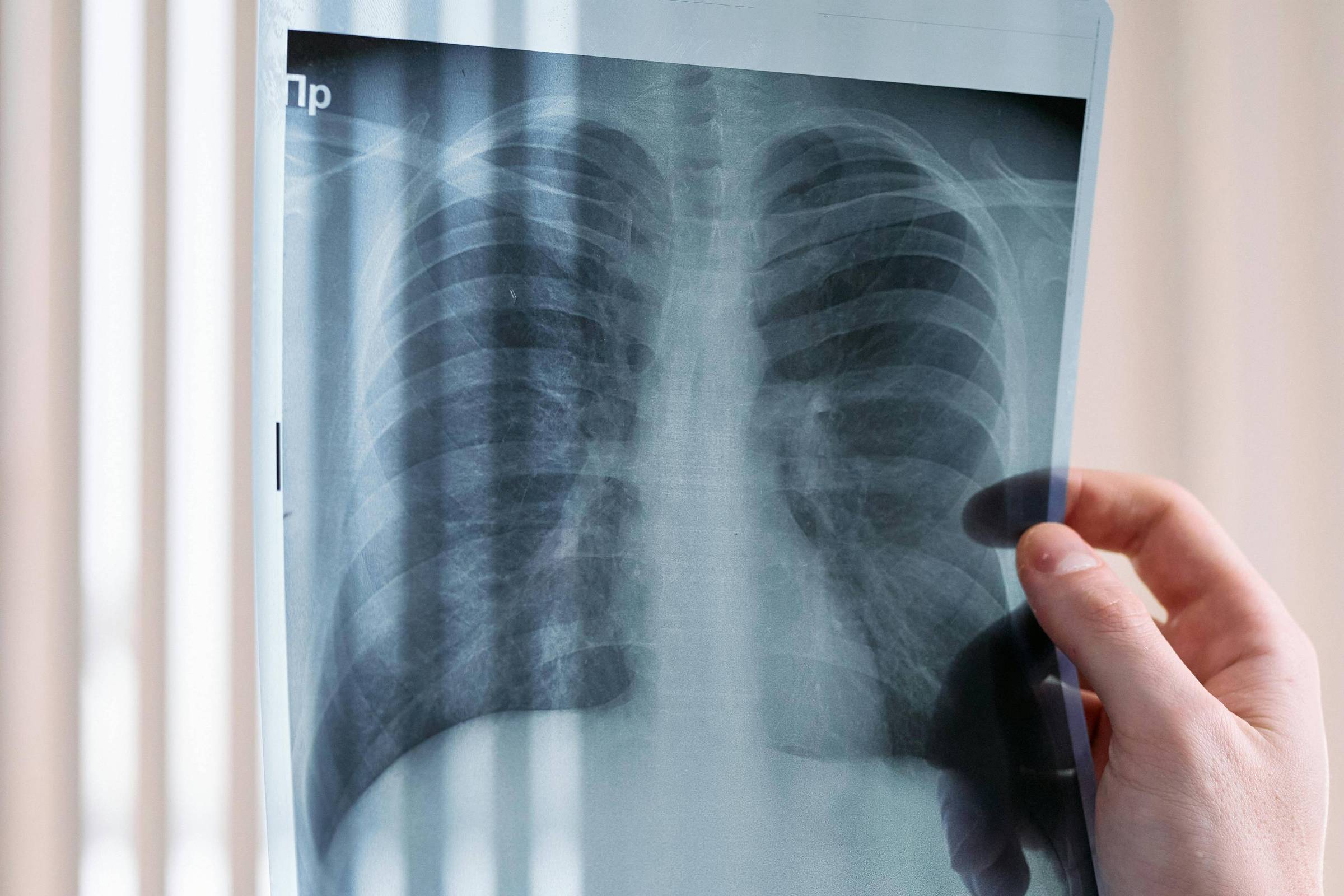

Early detection of genetic changes in lung cancer by liquid biopsy could become an important tool to accelerate diagnosis and guide treatment of patients in Brazil.

A Fapesp-supported study published in the journal Molecular Oncology has shown that it is possible to identify relevant mutations in blood samples from patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) using a commercial multigene panel. The research was carried out at Hospital de Amor (formerly Barretos Cancer Hospital), a national reference in oncology, and assessed the presence of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) in different groups of patients, including asymptomatic individuals.

Non-small cell lung cancer accounts for approximately 85% of cases of the disease, being the most common subtype. Within it there are different groups, such as adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Adenocarcinoma, in particular, is marked by the presence of mutations which have become the target of specific therapies, modifying the course of treatments in recent years. A little over ten years ago, median survival did not exceed eight months. Today, the scenario is different: we are talking about an overall survival of around two to three years if the patient receives targeted therapies, which can reach ten years in certain cases.

“Adenocarcinoma is the subtype of lung cancer that has benefited the most from advances in genomics and is therefore the main objective of our study,” explains researcher Letícia Ferro Leal, co-director of the study. “Genes such as EGFR, ALK and KRAS have what we call ‘actionability’. This means that when we identify such a change in the patient, there is a target drug that can act directly on them,” he explains.

In total, the study examined 32 plasma samples from 30 patients. Most of them had not received any treatment before, but previously treated patients and four participants in a lung cancer screening program were also included. The researchers then used a commercial panel designed specifically for known adenocarcinoma mutations and looked for changes in 11 genes linked to tumor development. The performance of the technique was surprising: 65.6% of samples presented mutations, this rate reaching 87.5% among patients who had already undergone therapy.

The most frequent mutations occurred in the TP53 (40.6%), KRAS (28.1%), and EGFR (12.5%) genes. Although TP53 is the most mutated gene in different types of cancer, there is still no specific drug to treat it. Modifications of EGFR and a specific modification of KRAS (p.G12C) are directly actionable – in the case of EGFR, with several drug options already approved in Brazil. One of them, the EGFR p.T790M mutation, linked to resistance to treatments, was identified in one of the samples analyzed.

“This type of mutation can appear even in patients who initially respond well to treatment. However, it is usually detected when the patient has already experienced disease progression. The same thing happens in patients with mutations in other genes, treated with other targeted therapies. This is a major challenge in oncology,” explains Leal.

One of the study’s most striking findings occurred in the screening group: An asymptomatic participant had a mutation in the TP53 gene six months before his cancer diagnosis. For researchers, this demonstrates the potential of liquid biopsy as a complementary tool for screening populations at risk, particularly smokers and ex-smokers.

Time is crucial

In clinical practice, the researcher explains, the big difference in performing a liquid biopsy for lung cancer is time. While conventional analysis of a tumor obtained by biopsy or surgery can take weeks from collection, sample processing, pathological evaluation and report release, liquid biopsy significantly shortens this process.

“Time is a crucial factor when talking about lung cancer. When we perform a tissue biopsy, we must take into account the patient’s waiting time to be able to schedule the biopsy or surgery. Only after this period does the time for sample processing and molecular analysis begin to count. In the best case, this report takes about two weeks from collection. With liquid biopsy, we take the sample at any time and the result can be published in two days, thus bringing forward the start of treatment,” explains the researcher.

In addition to agility and reduced response time, the study showed another advantage: the panel used was able to detect cDNA even in frozen samples, without the need for special tubes or immediate transport to specialized laboratories, as is often the case. This expands the possibility of adopting the method in public health services, which do not always have a complex structure for molecular testing.

Cost remains an obstacle

Despite the promising results, Leal recognizes that the incorporation of liquid biopsy into the routine of the public health system in Brazil still faces significant obstacles, especially economic ones. The test used in the study costs around R$6,000 per patient. Although this value may decrease with increased competition between genetic sequencing companies, this amount remains high for the majority of the population.

In the private sector, several targeted therapies are already available via the list of the National Complementary Health Agency (ANS). In the Unified Health System (SUS), options are rare and limited to a few reference centers, few of which are able to offer routine molecular testing. “Sometimes the patient can even pay for the test, but is unable to pay for the therapy, which can reach R$40,000 per month. This is why there are still many cases of judicialization,” comments Leal.